It's Spring 2040, and the U.S. population has grown by 41 million people since 2020 to over 373 million, fueled primarily by migration and longevity.1,2 The nation is more ethnically and racially diverse than ever. Until 2030, the average annual

increase in U.S. population growth remained at historical levels, but has declined throughout the last decade.3 The national median age has increased from 38.5 years in 2020 to 41.5 years in 2040, which sounds small until you realize that

this represents nearly 22 million more persons ages 75 years or older now than then.4 The youngest baby boomers are now 76 years old, Gen Xers are 60 to 75 years old, Millennials are 44 to 59 years old, and the oldest Gen Zers are in their

forties.

A health care 2040 leadership team — a diverse group composed primarily of Millennials and Gen Zers — is grateful that their counterparts in the early 2020s did not suffer from strategic myopia, despite being so focused on unprecedented ministry

challenges brought on by the times, including the pandemic, workforce shortages, financial pressures and market disruptions. Regardless of the hardships that they faced at the time, they still had the foresight to consider the longer-term implications

of changing U.S. demographics.

As health care leadership strategizes to address the needs of our nation's population, consideration of our changing demographics should play a substantial part in planning for what care will be needed and how it should be provided for future generations.

DEMOGRAPHY IS DESTINY

The quotation "demography is destiny" often is attributed to 19th-century French philosopher Auguste Comte. While perhaps in some ways simplistic or overstated, there is no question that the makeup of the population's

size, age, race, ethnicity and gender — commonly referred to as demographics — impacts its health needs. Anticipating our communities' future health needs, as well as the implications for the Catholic health care ministry's continued relevance

and mission fulfillment, require us to understand three interrelated demographic national trends:

- Slowing U.S. population growth.

- An increasing population of those over 65 years of age.

- Greater ethnic and racial diversity of our population.

SLOWING U.S. POPULATION GROWTH: THE 2030 TURNING POINT

The U.S. Census Bureau projects a slowing rate of U.S. population growth, with a turning point in 2030 when net international migration is expected to overtake natural increases (the excess of births minus deaths) as the driver of U.S. population growth.5 This change reflects a combination of relatively small growth in the number of women of childbearing age (females aged 15-44), declining fertility rates (births per 1,000 women of childbearing age), and an increase in the number of deaths among baby

boomers in older adulthood.6

Assuming that today's migration levels continue, between now and 2030, the nation's population is expected to grow by approximately 2.3 million people per year. However, this rate is projected to fall to an average of 1.8 million per year between 2030

and 2040.7 These figures are what the Census Bureau refers to as its "main series" projections and, unless otherwise noted, have been used throughout this article. Were the U.S. to have zero immigration, our 2040 population is projected

to be essentially the same size as in 2020, older (median age 43.3 years) and at that point declining slowly annually.8

Using these Census Bureau "main series" projections, the expected 2040 annual total population change of 1.7 million comprises only 600,000 from natural increases (births minus deaths) with the remaining 1.1 million accruing through net international

migration.

9

Projecting net migration is extremely challenging since it is impacted by economic and political factors, but the key takeaway is clear: without immigration, the U.S. population will shrink. Of course, no population growth takes place uniformly across

the country and a variety of factors come into play with population shifts, so we expect that regions that attract and retain immigrants may see stable or growing populations, with other areas experiencing population declines.

65 AND OLDER: POPULATION GROWTH

Because of large gains during the late 20th century, longevity is the new normal. The Census Bureau anticipates that by 2034 (and continuing into 2040), adults aged 65 and older are

projected to outnumber those under age 18 for the first time in U.S. history (see Figure 1).10 Some call this the "silver tsunami." Others see it as merely the first wave of elderly, to be followed in 2060 by a second wave of older adults,

made up of Millennials who currently outnumber baby boomers. Regardless, the baby boom "bubble" has caused economic and societal changes at every stage, and their demographic impact will continue to be dramatic through 2040 and beyond.

Clearly, the definition of elderly as those "65 and older" is outmoded, more appropriate in 1935 when Social Security was established than today. We know that health status and the demand for health care services — and the types of those services

wanted or needed — varies dramatically for those aged 65 to 74 years versus those aged 75 to 84 years, who again are markedly different from those 85 years or older.

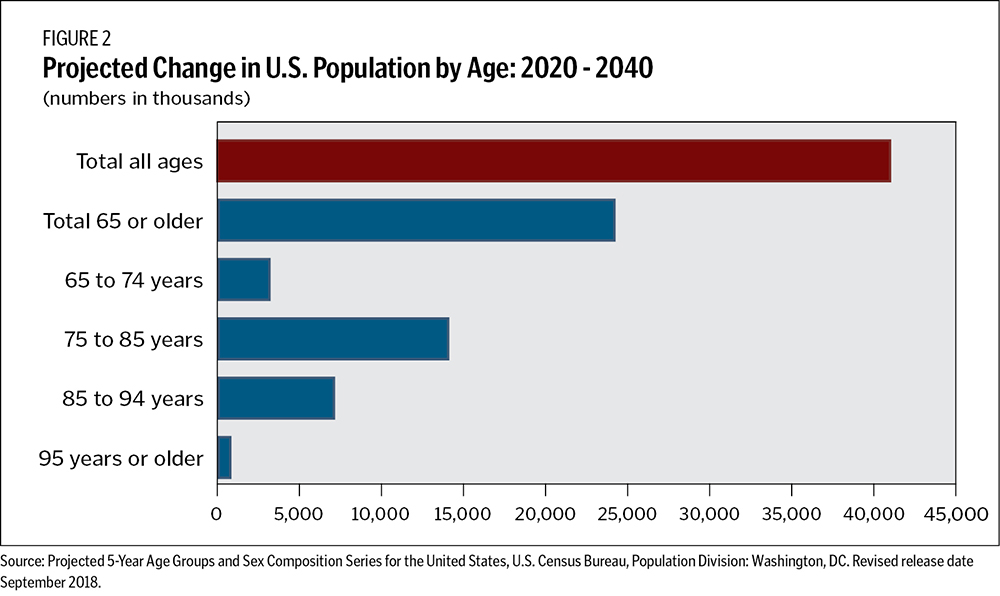

The Census Bureau's projections for 2040 anticipate that growth of those over 65 will account for more than 60% of the period's total population growth since 2020 (see Figures 1 and 2), with this cohort increasing by nearly 25 million persons (or more

than 40%).11 The vast majority of this older population's growth will occur among those reaching 75 years or older who, on their own, will account for more than half of total population growth.12 In other words, the baby boom

bubble will continue to travel through time.

The incidence and prevalence of chronic illness or age-related conditions such as dementia, especially among older adults, will generate an increase in demand for new models of health care. What will be needed will be more innovative virtual and home-based

models that deliver not only essential acute care services, but supportive services to meet peoples' changing social, emotional, housing and other needs as they age.

Those 18 to 64 years of age, historically described as "those of working age," are projected to increase from 2020 to 2040 by only 6% (as shown in Figure 1). This will exacerbate the current competition for scarce workforce talent, especially when recruiting

those 20 to 40 years of age, as well as a movement to recruit and retain staff over 65 years of age. Retiring at 65 may look less attractive when individuals have another 25 years or more to live, and many may look for new opportunities to redeploy

their skills.

Postponing retirement will be essential not only to ensure an adequate workforce to support growth across all economic sectors, but also to address the political and economic challenges created by an increasing "old-age dependency ratio" (see Figure 3).

This ratio is a measure of the potential burden on the working-age population, computed by comparing the number of individuals who are 65 and older to the number of those of traditional working age.13 The 2040 ratio of 37 means that there

will be a projected 37 people aged 65 and older (eligible for Medicare and, shortly thereafter, full Social Security) for every 100 working-age adults.

Finally, it is projected that the number of children will increase by only 4% during this period (refer to Figure 1) and will be likely to occur primarily in areas attracting immigrants.

POPULATION'S GREATER ETHNIC AND RACIAL DIVERSITY

In addition to projected changes in population growth and aging, the U.S. is projected to become a much more racially and ethnically pluralistic country. The only group projected to

shrink over the coming decades is the non-Hispanic white population, expected to decrease by approximately 10 million between 2020 and 2040. Despite this decline, non-Hispanic whites are projected to remain the single largest racial and ethnic group;

it is only in 2045 that they will no longer be projected to make up the majority of the U.S. population.14

The country's racial and ethnic diversity is most visible among children under age 18. A slight majority of those under 18 today already are of racial and ethnic minority groups other than non-Hispanic white, with this group making up an estimated 57%

of those under 18 by 2040. An even greater percentage of births that year are projected to be babies who are Asian, Black, Hispanic, two or more races, or other groups (includes babies who are American Indian and Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and

other Pacific Islander). The greatest projected absolute population increases for children are for those who are ethnically Hispanic and/or racially two or more races.15

We continue to be a nation of immigrants, with 44 million residents in 2020 — or more than one in seven — being foreign-born.16 If past trends continue, the Census Bureau projects more than 60 million foreign-born residents by 2040.

The share of foreign-born people living in the U.S. population hit a historic low in 1970 at only 4.7%. Since then, both the number and share of those who are foreign-born have grown steadily; and it is projected that by 2028, the share of foreign-born

will exceed the nation's historic high since 1850 of 14.8%. By 2040, it is projected that one in six residents will be foreign born.17

Over the past decade, more than 75% of those who are foreign-born have been of working age and generally more likely to hold full-time jobs than their native peers.

FOCUS ON 2040 DEMOGRAPHICS FOR FUTURE STRATEGIES

So, what do these demographic trends for a slower growing, aging and more racially and ethnically diverse future mean to us strategically? While every community will experience its

own demographic changes, there are several overarching implications for care delivery, ensuring the needed future talent and workforce, and advocacy.

Care Delivery: We need to design new delivery models built upon the needs and wants of an aging, consumer-oriented population.

- Stop thinking that "those over 65" are a monolithic group. Instead, understand the unique needs of different cohorts of older consumers, and design approaches that focus on sustaining their health and well-being as they age, rather than on primarily

diagnosing and treating their illnesses, too often on an episodic basic.

- Recognize that more than 75% of those 50 and older want to stay in their home and community as they age.18 Revolutionize your approaches to "care in the home" with a more intentional focus on enhancing your patients' emotional and spiritual

well-being and reducing social isolation.

- Leverage emerging technologies, including remote patient monitoring, to better and more cost-effectively serve your patients or residents in their preferred settings.

- Start using artificial intelligence to develop personalized care plans that can provide more precision treatments for chronic diseases of the elderly, such as diabetes and heart disease.

We also need to accelerate and sustain our efforts to reduce health inequities and disparities, especially as our population becomes so much more ethnically and racially diverse. To do this, we must:

- Recognize that moving the health equities needle will require "collective impact," collaborative networks of community members, health care organizations, academic institutions and the business community committed to advancing health equity and addressing

the social determinants of health.

- Simultaneously become a more culturally competent organization by creating more welcoming and inclusive health care settings through tailoring care delivery models to meet the diverse social, cultural and linguistic needs of those we serve.

Future Workforce: Today's children under 18 are 2040's younger workforce. There will be tremendous competition from all industry sectors for this relatively small talent pool. We must:

- Start now to cultivate relationships with schools, houses of worship and community organizations to expose this diverse group to opportunities in health care.

- Redesign both our work and our work environments to attract members of the highly diverse and technology savvy members of Gen Z and Generation Alpha (those born after 2013).

For our future workforce of all ages, we must:

- Shift the focus of our human resources efforts from "diversity" to "inclusion," expanding on our notions of cultural competency to also include meeting the diverse social, cultural and linguistic needs of our staff.

- Offer new tools and approaches for "lifelong learning" both to retain staff and to attract new staff members.

- Reimagine roles for those nearing traditional retirement age.

Advocacy: Immigration has been and will continue to be the lifeblood for our overall economy. Without immigration, our population will shrink. Continued advocacy on this issue may seem Sisyphean, but it has never been more essential.

Additionally, given the "old-age dependency ratios" (see Figure 3) there will be a tremendous need to advocate for fair and adequate public payments against the headwinds of a substantially aging population with relatively fewer workers to

financially support the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

CONCLUSION

Some of the projected demographic shifts are a continuation of the American experiment, where waves of those born elsewhere seek expanded opportunities in a new homeland. However, our upcoming demographic turning points

will be unique and challenging as we seek to create a vibrant, more racially and ethnically pluralistic country while simultaneously attending to the needs of an aging population. Demography may not determine destiny, but it certainly has its hand

on the tiller.

MARIAN C. JENNINGS is president of M. Jennings Consulting, Inc., in Malvern, Pennsylvania. She recently served on the Editorial Advisory Council for Health Progress.

NOTES

- "U.S. and World Population Clock," U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/popclock/.

- Jonathan Vespa, Lauren Medina, and David M. Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060," U.S. Census Bureau, February 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points for the United States."

- "Census Bureau Releases 2020 Demographic Analysis Estimates," U.S. Census Bureau, December 15, 2020, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/2020-demographic-analysis-estimates.html;

"Projected 5-Year Age Groups and Sex Composition Series for the United States," U.S. Census Bureau, https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popproj/tables/2017/2017-summary-tables/np2017-t3.xlsx.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points for the United States."

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- Sandra Johnson, "A Changing Nation: Population Projections Under Alternative Immigration Scenarios," U.S. Census Bureau, February 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1146.pdf.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- Lauren Medina, Shannon Sabo, and Jonathan Vespa, "Living Longer: Historical and Projected Life Expectancy in the United States, 1960 to 2060," U.S. Census Bureau, February 2020, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1145.pdf.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- "Projected 5-Year Age Groups and Sex Composition Series," U.S. Census Bureau.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- "Citizenship and Immigration Statuses of the U.S. Foreign-Born Population," Congressional Research Service, July 18, 2022, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/homesec/IF11806.pdf.

- Vespa, Medina, and Armstrong, "Demographic Turning Points."

- "AARP Survey Shows 8 in 10 Older Adults Want to Age in Their Homes, While the Number and Needs of Households Headed by Older Adults Grow Dramatically," AARP, November 18, 2021, https://press.aarp.org/2021-11-18-AARP-Survey-Shows-8-in-10-Older-Adults-Want-to-Age-in-Their-Homes-While-Number-and-Needs-of-Households-Headed-Older-Adults-Grow-Dramatically.

Copyright © 2023 by the Catholic Health Association of the United States

For reprint permission, contact Betty Crosby or

call (314) 253-3490.