SALLY J. ALTMAN, MPH AND RICHARD H. WEISS

Contributors to

Health Progress

Illustration by Cap Pannell

Illustration by Cap Pannell"The hurrier I go, the behinder I get," said the white rabbit in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. So many people in public health could be forgiven if they expressed this sentiment as well. While the public health sector has made substantial

progress in fostering healthy communities by identifying and, more importantly, addressing the social determinants of health, the nation has moved backwards.

U.S. life expectancy peaked in 2014 at 78.9 years and then fell or stayed flat until 2019. By 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy plummeted to 76.4 years. Life expectancy rebounded by about a full year by 2022, and that is a positive development,

but it's less than half of what was lost during the height of the pandemic, and less of an increase from similarly wealthy nations, according to an analysis in The Washington Post using Centers for Disease Control data released in late November.1

Healthy Communities: It is a term that public health workers and policymakers have embraced as a way of defining and coming to grips with the factors that either inhibit or advance longevity and quality of life. It suggests that we are all in this together

and that it takes everyone collaborating to improve outcomes. Healthy communities are hyperlocal and unique. People working in the field reject cookie-cutter and top-down approaches.

They recognize that "progress moves at the speed of trust" in an age when misinformation moves at the speed of social media and there is so much civic mistrust.

The current state of healthy communities is a complex blend of progress and persistent hurdles — ones that seem to grow larger almost every day. Among the obstacles:

- The opioid epidemic.

- Rising suicide rates.

- Increases in chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes and certain cancers.

- Increases in infectious diseases, including COVID.

- Climate change and environmental disasters.

- Pollution.

Then layer on top of all these issues limited access to health care, especially in marginalized communities.

And yet, at the same time, public health workers and community organizers have learned much about what works to address health needs and how to work with disparate groups to make healthy outcomes happen.

However, implementing these solutions takes time to plan effectively, and, more importantly, a recognition by all involved that structural change is needed to start creating healthier communities.

CREATING ACCOUNTABLE COMMUNITIES

You can find in public health literature hundreds of success stories, including a 23-page report from Raising the Bar, a nonprofit project funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, titled simply

and hopefully: Bright Spots.2

"I think we're headed in the right direction," said Sara Singleton, a principal at Leavitt Partners and an advisor to the National Alliance to Impact the Social Determinants of Health.3 "But these are huge problems, and we're not going to solve

any of those immediately, fast or easily."

Jeffrey Levi, who recently retired as a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University, refuses to be pessimistic. For decades, Levi led research into the intersection of public health, the health care system and the multisector

collaborations needed to improve health.

"I think there is a movement out there that recognizes social needs are really important to health outcomes. But you have to figure out how health and social services come together. A lot of it on the ground is about people and personalities and how they

have relationships. And some of those relationships are toxic." But, he added, "Some of them are great."

Last year, Levi co-authored a discussion paper assessing Accountable Communities for Health,4 a descriptor signifying an organization's responsibility for the health of a community and a two-way collaborative relationship.

He adds that hospitals need to focus more of their work at a neighborhood level in a way that supports community health. "We have had a tendency in the United States to medicalize everything and to prefer a biomedical intervention over structural change,"

he said.

That has led to an emphasis on addressing diseases one person at a time with increasingly expensive procedures and medications, Levi said. Too little attention is paid to prevention and the structural issues that lead to disease. "Clean water is not really

a biomedical intervention. It's a structural intervention. Clean air is a structural intervention. That is something we have to come together as a society to address," Levi said.

"It has been just over the last 20 or 30 years that we've developed this much deeper understanding of what influences health outcomes," Levi continued. "When you look at the data, when you look at what will extend life expectancy … education matters,

employment matters, housing matters. And those have to be addressed at the community level. Though hospitals are at the forefront when it comes to treating disease, they also need to play a role in saying to policymakers, ‘We need to improve

housing, we need safe streets, we need to reduce smoking. We need to do all sorts of things without medicalizing them.' And that requires partnerships."

Levi and his co-authors identified more than 125 Accountable Communities for Health nationwide at various stages of development. "ACHs are, above all, about changing how a community creates the conditions for health and how it shares power, particularly

among low-income populations, people of color, and other underserved populations," they wrote.

Singleton and others have noted that underserved communities often are literally in the shadow of some of the nation's most esteemed medical centers, whether it's New York, Los Angeles, St. Louis or Cleveland. But, sounding a note of optimism, Singleton

said, "Health care institutions have really taken their role in the community seriously and said, ‘You know, we're not just providing health care services … this is where our staff lives and works, and we need to make it a better place.'"

Singleton points to Cleveland and its MetroHealth System as a particularly inspiring example. "They have come together on some substantial issues that have plagued the community," she said. Catholic health care organizations are part of some of the community

collaborations described in this article.

MetroHealth serves more than 300,000 patients, with 75% uninsured or covered by Medicaid or Medicare.5 After the police murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the unrest that followed, the senior leaders brought together both patients and employees

for conversations to improve equity. This led to concrete steps to develop partnerships with local food banks, the legal aid society and assistance in building affordable housing units.

MetroHealth also developed a school health program serving students in more than 25 schools throughout Northeast Ohio. Last academic year, the program, which has more than 4,000 enrolled students, assisted with nearly 3,900 clinical visits. This academic

year, MetroHealth expanded services to students' families and school staff.

Particularly novel is the Lincoln-West School of Science and Health, believed to be the first high school within a hospital.6 Juniors and seniors attend classes at the hospital full-time for training in health care, environmental science and

culinary arts.

Photo by Darrel Ellis with permission from The Kresge Foundation

Photo by Darrel Ellis with permission from The Kresge Foundation

Children at the LACC Childcare Center in Detroit play and learn at one of the more than 80 sites with facility improvements, facilitated through IFF's Learning Spaces program.

The focus on safe, inspiring spaces is part of Hope Starts Here, a multiorganization effort to improve access, quality and affordability in child care and early education in Detroit.GENERATING BUY-IN

The past 25 years saw the evolution toward community-centered collaboratives to address the structural and systemic factors that affect how long and how well people live. Cross-sector collaborations at the local

level bring together public health, health systems, business, government and nonprofit community-based organizations to establish collective goals, develop action strategies, designate accountability and track metrics to sustain progress.

National League of Cities is among several organizations that have developed a theory of change. As stated in the league's model of change as part of its Cities of Opportunity initiative: "Cities are uniquely positioned to address social determinants

of health and racial disparities, and to advance equity and well-being for all residents."7

Accordingly, they have a framework for how stakeholders can collaborate on inclusive strategies and stimulate buy-in.8 "Up to 80% of the factors that define well-being, opportunity and dignity are determined in our neighborhoods, schools, places

of worship and jobs, and by our policies and community structures," the National League of Cities notes. "It's vital for cities and their people to have the right set of data to clearly see and solve for these multiple factors … ."9

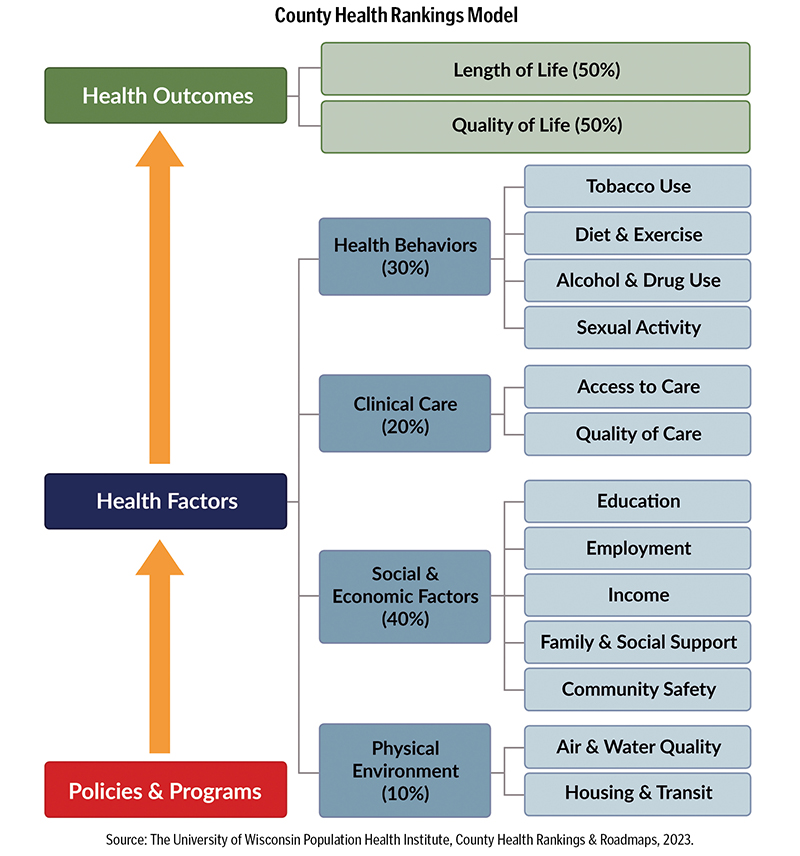

The County Health Rankings Model10 (see model above) had a defining impact in bringing new players to the table who may not have realized they had a powerful role in improving health. These included county and city governments, local United

Ways, businesses, schools and local nonprofits. Developed more than a decade ago at the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, the rankings show the many factors that affect health — from tobacco use, diet, exercise and sexual

activity, to level of education, to air and water quality to housing and transit — in nearly every county in all 50 states. The institute's website also provides tools and resources designed to foster community action.11

Kitty Hsu Dana has seen the "aha!" impact of the County Health Rankings on mayors and United Way CEOs in recognizing the role they play in the health of their communities. She has worked for three decades in hospital settings and through leadership roles

in the American Public Health Association, United Way and the National League of Cities. "We have the highest health expenditures of any nation, with almost all the resources going to health care services and less than 3% to public health and prevention.

And the U.S. is way behind other high-income countries in investing in upstream social services for children and working-age adults: equitable economic development, child care, parental leave or basic affordable and healthy housing," she said.12 "All of these factors affect health outcomes."

As senior health policy advisor at the National League of Cities, Hsu Dana led the design and implementation of the Cities of Opportunity initiative to address social determinants of health and racial disparities and to advance equity and well-being for

residents. Local governments in Cities of Opportunity convene stakeholders to develop inclusive strategies and stimulate buy-in. Currently, Hsu Dana serves as president of the board of directors of the Prevention Institute and sits on the board of

advisors of Healthy Places by Design. Both organizations advance community-led action to address systemic factors that affect health and well-being in a collaborative, integrated way.

Of course, in today's politically polarized environment, that can sound too much like socialism to some ears.

To that, Hsu Dana answered: "We do need to know how we sound to others. I think one of the mistakes liberals make is thinking that people just aren't getting it and we just need to feed them more facts. Rather than listen to their aspirations, needs and

concerns, we can come across as judgmental. So I am a big believer in the power of local leadership, especially in smaller towns and cities where they can have a dialogue." That's important, Hsu Dana notes, at a time when economic inequality, social

isolation and political polarization are stark.

She adds: "I don't know of any one community that has gotten it all down right in a sustained way. What I do know is there are many cities — even the larger ones — that are making traction. They are in the process of building trust and following

up with action. It absolutely has to start with listening to people in the community. Communities where trusted leaders were engaged — for example, the faith leaders, the fire chief — did a whole lot better during the COVID pandemic, helping

people understand certain practices that kept people healthy. The community is the unit of transformation."

MAKING CHANGE GENERATION TO GENERATION

Making an impact on life expectancy with interventions is important for every age cohort, but it is particularly important and challenging for children and older adults.

In Detroit, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and The Kresge Foundation invested $50 million in 2016 to seed Hope Starts Here, a coalition of advocates for early childhood systems.13 To that point, Detroit had a well-deserved reputation for dysfunction

when it came to early childhood. Nine percent of Detroit moms got either late or no prenatal care and, at one point, the city had the highest rate of infant mortality in the country, with 13.5 of every 1,000 babies dying before their first birthday.

More than 60% of Detroit's children aged 5 and under were living in poverty.14

Since then, Hope Starts Here has engaged thousands of Detroit residents — families, childcare providers, health care professionals and educators — to develop strategies and actions to advance early childhood development.

The organization defined six imperatives15:

- Promote the health, development and well-being of all Detroit children.

- Support parents and caregivers as children's first teachers and champions.

- Increase the overall quality of Detroit's early childhood programs.

- Guarantee safe and inspiring learning environments for children.

- Create tools and resources to better coordinate systems that impact early childhood.

- Find new ways to fund early childhood and better use the resources at hand.

Hope Starts Here has defined 15 actions to achieve their goals by 2027.16

As for seniors, Sandy Markwood, CEO of USAging17 — a national association that supports the network of Area Agencies on Aging — notes that by 2034, there will be more people over age 65 than under 18. She adds that seniors have

much to offer, both economically and socially, but because of ageism are not valued by society, which tends to focus on the deficits of aging rather than its assets.

That said, the demographics of aging do present issues that should be addressed. Too few older adults plan for the time when they will need more support. And too few take advantage of services already in place that could both lengthen and enhance the

quality of their lives. So yes, at some point there is a cost to providing care for older adults. But the evolution of services is ongoing, so that many older adults have greater choice in their care through offerings like increased home care options.

But providing care and support is only part of the equation. "We also need to focus on the fact that the nation's increasing population of older adults represent a demographic powerhouse," Markwood said. "Older adults and their 53 million caregivers can

be economic drivers in this country. What if we looked at our aging population that way, and communities responded by focusing on being healthy communities for a lifetime?"

So, like other thought leaders mentioned here, Markwood references community-based solutions that engage stakeholders across a wide spectrum. One program she holds out as a model serves small towns located in the 10 counties known as Middle Peninsula

and Northern Neck in the Virginia Bay area. These towns are fully or partially designated as medically underserved areas by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. Many residents are extremely isolated and in need of services.

The effort is organized through Bay Aging,18 an Area Agency on Aging, which has formed partnerships with federal, state and local governments; community and civic groups; faith communities; and businesses.

Among its achievements, Bay Aging:

- Serves more than 30,000 people through housing, transportation and health-related services statewide each year.

- Participates in the Northern Neck/Middle Peninsula Telemedicine Consortium, which Bay Aging helped to establish, connecting rural health providers with the University of Virginia's telemedicine system.

- Administers funds for residential improvements, including more than $53 million in single-family project funds that supported such programs as weatherization, indoor plumbing rehabilitation and emergency home repairs.

- Secures housing, including investing more than $50 million for the acquisition and/or development and operation of 12 rental housing communities that helped to address homelessness in the region.

- Finds housing for community members in need, including placing more than 400 people (193 households) in safe and affordable homes through the Housing Choice Voucher Program (widely known as Section 8) and lifted 534 people (210 households) out of

homelessness through the Rapid Rehousing program in fiscal year 2023.

Like every other advocate for healthy communities, Markwood recognizes the political environment is hazardous. The Older Americans Act comes up every five years for reauthorization. It provides critical supports for various social services and programs

for citizens 60 and older. Some of these include a range of supportive services, congregate nutrition services (for example, meals served at group sites such as senior centers, community centers, schools, churches or senior housing complexes), family

caregiver support, and services to prevent the abuse, neglect and exploitation of older persons. Since its inception in 1965, it has always drawn bipartisan support.

But Markwood recognizes we live in a time when popular programs risk being held hostage or used as bargaining chips. "The OAA [Older Americans Act] is on the discretionary side of the budget," she acknowledges. "So, you have to fight for appropriations

every year for these programs, and that's hard. But we see this as an important commitment to older adults to ensure that they can live with dignity and independence in their homes and in their communities.

"We look at aging not as a red or a blue issue," Markwood said. "Everybody is aging if they are lucky."

Markwood, Singleton, Levi and Hsu Dana note that the journey toward healthier communities involves triumphs and persistent challenges. From addressing the opioid epidemic, homelessness and rising suicide rates to grappling with chronic diseases, infectious

outbreaks and environmental concerns, the landscape is complex. While the nation's life expectancy has declined, there's a resilient spirit among public health workers, community organizers and leaders, and an increasing recognition that collaborations

— complicated as they may be — are crucial.

Or, as the Dodo declared in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland: "The best way to explain it is to do it."

SALLY J. ALTMAN has devoted her career in public health to working with key stakeholders on health access issues as a health care administrator and a journalist. RICHARD H. WEISS is a journalist and co-founder and current

chair of the River City Journalism Fund, a nonprofit, social justice storytelling project that addresses the need for better representation of historically marginalized communities in metropolitan St. Louis.

NOTES

- Joel Achenbach and Dan Keating, "New CDC Life Expectancy Data Shows Painfully Slow Rebound From Covid," The Washington Post, November 29, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2023/11/29/life-expectancy-2022-united-states/.

- "Framework in Practice: Bright Spots," Raising the Bar, 2022, https://rtbhealthcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/RWJF-RTB-Report-2022-BRIGHT-SPOTS-FINAL-060622.pdf.

- National Alliance to Impact the Social Determinants of Health, https://nasdoh.org.

- Helen Mittmann, Janet Heinrich, and Jeffrey Levi, "Accountable Communities for Health: What We Are Learning from Recent Evaluations," NAM Perspectives (October 31, 2022): https://doi.org/10.31478/202210a.

- "About MetroHealth," MetroHealth, https://www.metrohealth.org/about-us.

- "MetroHealth Develops Diverse Healthcare Leaders Through Nation's First High School Inside a Hospital," Creating Healthier Communities, November 18, 2022, https://chcimpact.org/metrohealth-develops-diverse-healthcare-leaders-through-nations-first-high-school-inside-a-hospital/.

- "Cities of Opportunity Theory of Change," National League of Cities, https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NLC-COO-TOC-102821-regular-original-format-FINAL.pdf.

- "Cities of Opportunity Theory of Change," National League of Cities.

- "How Cities Can Redefine Progress Toward Equity for Well-Being," National League of Cities, https://www.nlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/NLC-WB-message-guide_final-11-12-21__508-Compliant.pdf.

- "County Health Rankings Model," County Health Rankings & Roadmaps, https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/explore-health-rankings/county-health-rankings-model.

- "County Health Rankings & Roadmaps," University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, https://uwphi.pophealth.wisc.edu/chrr/.

- Dr. David U. Himmelstein and Dr. Steffie Woolhandler, "Public Health's Falling Share of U.S. Health Spending," American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 1 (January 2016): 56-57; Eric C. Schneider et al., "Mirror, Mirror 2021 — Reflecting Poorly:

Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries," The Commonwealth Fund, August 4, 2021, https://doi.org/10.26099/01DV-H208.

- Hope Starts Here, https://hopestartsheredetroit.org; Margo Dalal, "Fueled by Community Input, Foundations Unveil Comprehensive Early Childhood Education Initiative,"

Model D, December 11, 2017, https://www.modeldmedia.com/features/hope-starts-here-unveil-121117.aspx.

- "Hope Starts Here: Detroit's Community Framework for Brighter Futures," Hope Starts Here, November 2017, https://hopestartsheredetroit.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/HSH-Full-Framework_2017_web.pdf.

- Hope Starts Here Imperatives, Hope Starts Here, https://hopestartsheredetroit.org/imperatives/.

- "Hope Starts Here Unveils 10-Year Community Framework to Improve Early Childhood Outcomes for Detroit," Hope Starts Here, November 10, 2017, https://hopestartsheredetroit.org/blog/hope-starts-unveils-10-year-community-framework-improve-early-childhood-outcomes-detroit/.

- "About Us," USAging, https://www.usaging.org/about.

- Bay Aging, https://bayaging.org.