By LISA EISENHAUER

Dr. Zachary Risler can count on treating at least one patient every shift in the emergency room at Nazareth Hospital in Philadelphia who is either in the midst of an acute drug overdose, in need of care for recalcitrant wounds caused by injecting street

drugs or dealing with another medical condition that has been spawned or worsened by substance abuse.

Risler

RislerMost likely, he says, many of the patients have injected opioids cut with xylazine, a drug known on the street as tranq. Xylazine is a veterinary tranquilizer and painkiller with no approved uses in humans. It is widely present in opiates sold on the

street in Philadelphia.

Routine toxicology tests done by hospitals don't screen for xylazine, so Risler and his colleagues look for the clues that point to the drug. One clue is if the patient is in the midst of an acute overdose and unresponsive to the opiate reversal medication

naloxone. Black wounds are another.

"I think the big thing that we're seeing are people that show up with these really bad wounds, something called eschar, which is necrotic or black wounds," Risler says. The wounds, much like those from thermal or chemical burns, pose risks for infection

and disfigurement. The wounds can require intense and long-term medical care.

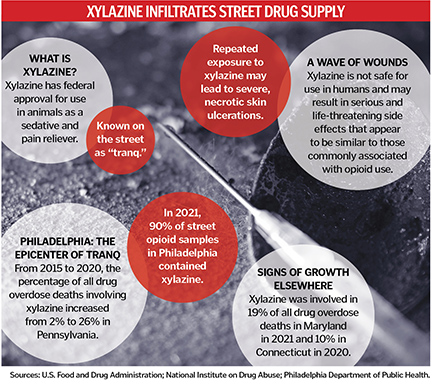

Worsening epidemic

The spike in prevalence of xylazine in street drug supplies of opiates is exacerbating an unchecked epidemic that already claims an alarming number of lives. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 80,816 fatal overdoses — 75% of all overdose deaths — in 2021 involved opioids. The number of opioid-related fatal overdoses in 2010 was 21,088.

A report published in April 2022 in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence says xylazine is increasingly present in overdose deaths. In 10 jurisdictions

across the nation that were studied, detection of the drug in overdose deaths went from 0.36% in 2015 to 6.7% in 2020. The highest xylazine prevalence was in Philadelphia (25.8% of overdose deaths), followed by Maryland (19.3%) and Connecticut (10.2%).

The National Institute on Drug Abuse says the number of opioid overdose deaths involving xylazine is unknown. "Most overdose deaths linked to both xylazine and fentanyl also involved additional substances, including cocaine, heroin, benzodiazepines, alcohol,

gabapentin, methadone, and prescription opioids," according to a research brief from the agency.

The brief describes xylazine as a central nervous system depressant that can cause drowsiness and amnesia. It says the drug can "slow breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure

to dangerously low levels." Repeated use of xylazine, the institute says, is associated with skin ulcers, abscesses, infections that can extend into bones and related complications. The institute says people report injecting, snorting, swallowing

and inhaling drugs containing xylazine.

Labs can use additional analytical processes to detect xylazine in blood. Toxicology results from patients who fatally overdosed in Philadelphia and other drug hotspots across the nation show increasing evidence of xylazine abuse, the institute says.

And deaths involving xylazine have been spreading westward from an epicenter in Northeastern states.

A street scene in Philadelphia, a center of xylazine abuse. The animal tranquilizer, which has no approved human uses, was found in 90% of street drugs tested by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health in 2021. The number of fatal overdoses in

Philadelphia in which xylazine was detected rose from 15 in 2015 to 434 in 2021.Credit: Sipa USA/Alamy Stock photo

A street scene in Philadelphia, a center of xylazine abuse. The animal tranquilizer, which has no approved human uses, was found in 90% of street drugs tested by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health in 2021. The number of fatal overdoses in

Philadelphia in which xylazine was detected rose from 15 in 2015 to 434 in 2021.Credit: Sipa USA/Alamy Stock photoResearch suggests that people suffering from substance use disorder began using xylazine in Puerto Rico in the early 2000s. Then the drug found its way into the opiates

being sold illicitly in cities with large Puerto Rican populations. Users report that xylazine prolongs the euphoric effects of fentanyl, the synthetic opioid that is largely

blamed for the widening overdose epidemic.

Philadelphia's Department of Public Health says xylazine was first detected in the street drug supply there in 2006. By 2021, the agency reports,

90% of street opioid samples contained xylazine. The number of fatal overdoses in Philadelphia in which xylazine was detected spiked from 15 in 2015 to 434 in 2021.

FDA issues alert

Still, xylazine remained largely under the national radar until last November, when the Food and Drug Administration issued a warning to health care professionals. The warning says the agency is aware "of increasing reports of serious side effects from individuals exposed to fentanyl, heroin, and other illicit

drugs contaminated with xylazine."

The warning notes that naloxone may not reverse the effects of opioid overdose when xylazine is present. In such cases, the FDA says clinicians "should provide appropriate supportive measures."

Risler says that's what he and his colleagues do at Nazareth, a Trinity Health hospital in a working-class section of north Philadelphia. Supplemental oxygen to counter suppressed breathing is one of the supportive measures Nazareth clinicians provide

to patients. Some patients with life-threatening respiratory suppression require intubation.

Because patients who have taken xylazine along with an opioid usually have been unconscious for a while when they are brought into the ER, Risler says when they regain consciousness the rush of the opioid has most likely worn off or been reversed by naloxone.

That can leave them in what he describes as withdrawal with intense drug cravings.

"It's just this tough balance between making sure that they survive an acute overdose and then convincing them that we're here to help them and try to get them the care they need," Risler says.

Nazareth has social workers in the ER who can provide warm handoffs to rehab programs. It sends kits with two doses of naloxone home with patients who are abusing opioids.

On the alert

In St. Louis, Drs. Steven Lorber and Mick Kilkelly haven't seen evidence of xylazine use in patients being treated for drug overdose at SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital.

Lorber

Lorber"It's probably here," says Lorber, SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital's chief of emergency medicine. "It's just that we're not seeing it because we're not looking for it."

Given the uptick in xylazine's presence in street drugs elsewhere, Lorber and Kilkelly are on the alert.

Kilkelly

KilkellyKilkelly, division chief of adult anesthesiology and medical director of SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital's operating rooms, points out that heroin and methamphetamine have long been cut with baking soda, baby powder and other substances that

don't have much of an impact on users. "But this stuff (xylazine) does create these devastating wounds that take a tremendous amount of time, energy and effort and health care resources to heal," he says.

Demand and supply

Lorber and Kilkelly say xylazine's spread in the street drug supply is to be expected for several reasons. One is that there seems to be demand for the drug. Another is that xylazine is currently not classified as a controlled substance. Even if drug enforcement agents or police find a trafficker with a stash of xylazine, the possession will not prompt charges.

"It's not illegal to possess xylazine," Kilkelly says. "You can have cases of this stuff in your trunk and get pulled over, and the officer has no legal authority to do anything."

The doctors also say that much like fentanyl, xylazine apparently can be easily manufactured in a lab. "The purity is probably very, very high and it's highly concentrated," Lorber says. "So, it's this very small amount of chemical that you need that

you can then cut to make a great deal of product to sell."

The SSM Health Saint Louis University Hospital doctors note that in the U.S., drug trends tend to start on the nation's coasts or southern border and then move inland. They are hoping that before xylazine becomes more prevalent in the Midwest they and

other care providers have time to educate themselves about how to detect the drug's presence and treat patients who have developed dependencies to it. They also hope to get a jump start on informing the public and the substance-abusing community on

xylazine's risks.

As to how to curtail the supply of xylazine, Kilkelly and Lorber expect that federal regulators will eventually add the drug to the list of controlled substances and policymakers will make its unauthorized manufacture and possession illegal. That, they

say, will spur the development and use of simple tests that can detect xylazine in drug supplies and in toxicology tests of patients being treated for overdose.

Compassionate care

In the meantime, the St. Louis doctors are looking toward the East Coast to see what best practices their peers identify for treating patients harmed by xylazine use.

Nazareth is the third hospital in Philadelphia where Risler has worked. At each one he has helped treat a population of patients with substance dependency disorders and related comorbidities.

"I think you quickly realize that none of them want to be in the position that they're in," he says. "It's just these drugs are so addictive, it's hard to get over that. We are just treating them with the most compassionate care that we can and kind of

meeting them where they are and just doing everything we can to help."