BY: FRED ROTTNEK, MD, MAHCM

I never expected to go to jail. As a good Catholic boy, middle child of three in a good Catholic household of working-class parents in St. Louis, I grew up with the very best of intentions. I wanted to do something with my life worthy of the talents that God gave me. And I cultivated those talents, particularly in school, at a ferocious pace.

I entered medical school at Saint Louis University and, unknowingly, began building my future practice as I chose electives that involved caring for the city's homeless population. I loved it. After graduation, I found my comfort zone in a family medicine residency focused on community-based experience, keeping out of hospitals' marble lobbies with water features! I was more comfortable caring for patients in homeless shelters and in the chaos of a children's home.

After I completed the family medicine residency, I joined the program's faculty. The St. Louis County Health Department approached my boss about staffing the three county health centers with family physicians. He was hesitant when he learned the county jail and juvenile detention center were part of the deal. I told him that if we got the contract, I would take the assignment in corrections. In the shelters, I had been caring for the correctional system's frequent fliers — the homeless, the poor and those without resources. These people had become my cherished patient population.

That was 15 years ago. And for almost 13 years, I have been the contracted medical director for corrections in St. Louis County and the chief physician at the jail and juvenile detention facilities.

I never expected to spend time behind bars. But the last 13 years have been among the best of my life. I love my work. I love being in jail.

JUST ANOTHER DAY IN FAMILY MEDICINE

We provide health care for murderers and rapists, thieves and punks, deadbeat dads and sex offenders. We provide care for alcoholics and addicts. We provide care for chronic schizophrenics and people with undiagnosed mood disorders. Most importantly, we care for people.

It is hard, grinding and unrelenting work, but it is rewarding and meaningful. It forces me into daily reflection in order to stay fresh, engaged and focused. After all, about 35,000 arrestees come through our intake department on an annual basis; all receive a medical evaluation by our registered nurses. I have an active daily patient panel of about 1,325 people.

After people ask me why I do this work in the first place, they often ask how I find the resilience to face the job, day after day. While I always have been an innately reflective person, I broadened this skill and found anchors for my work through studies at Aquinas Institute of Theology in St. Louis. In 2001, I became a member of the first cohort of the Aquinas Health Care Mission program. There, my passion in ministry and professional formation was fed with a diversity of approaches and participation in Catholic health care.

In the health care mission program, I found both a broader view of health care and an enhanced understanding of healing and the deeper story of health care as ministry. But I brought with me my experience as a medical practitioner in the messy world of public and community health. I was the one who would ask, over and over, "When we say that Catholic health care is a healing ministry of the church, do we say so because we believe it — or do we say it just to make us feel better about ourselves?"

My classmates gave meaningful responses, but the responses varied by the systems they represented. Some Catholic systems took a proactive, collaborative approach with community partners such as federally qualified health centers and small family-owned businesses. Other classmates were somewhat embarrassed by the business practices that their systems engaged in for the purpose of market dominance. All felt that their systems could do more with care of the marginalized, including the homeless, the undocumented and the incarcerated. But bringing together system leaders who shared a vision for this type of ministry was daunting and discouraging. Maintaining a functional fiscal model in the rapidly shifting world of health care was the dominant concern; creatively expanding mission through less secure funding streams — if any funding streams at all — was not the priority. I was not in a position to push for large-scale change at that time.

Ten years later, experience, struggle and partnerships have given me a stronger voice and a much broader vocabulary. I am currently a member of no traditional parish. Instead, my parish is Saint Louis University; my community is correctional health care. I am convinced my work, and the work that surrounds me, is a healing ministry of the church. And this ministry is local. I believe it is time for the church to revitalize its role in this mission.

JAILHOUSE MEDICINE

People do not aspire to be in jail. The majority of our patients are people who engaged in behaviors that resulted in incarceration. Something went terribly wrong at some point in their lives, and we seek to provide the best care possible to individuals whose health problems are only part of the story. Sometimes that means treating our patients with more respect than they have for themselves: The pregnant woman who didn't know she was pregnant and was drinking a gallon of vodka a day. The man who never took care of his post-operative gunshot wound correctly, and, as a result, has been walking around for the past few years with an abdominal cavity that is, essentially, a pocket of pus. The actively psychotic schizophrenic woman who screamed in our psychiatry infirmary for five months of her pregnancy. The 12-year-old boy who raped and almost murdered a 6-year-old girl.

We have built an interprofessional program with academic collaborations with Saint Louis University (where I am now full-time faculty), the St. Louis College of Pharmacy, Washington University and the University of Missouri-St. Louis. We proudly and enthusiastically include students and residents of a dozen professions into our daily work and ongoing projects.

The St. Louis County jail is the only jail in Missouri that is accredited with the American Correctional Association. This certification requires that we meet or exceed hundreds of standards, including health care, housing, nutrition, staff ratios and ongoing professional training. We promote our work at local, regional and national venues. And our practice is far safer than any emergency room I have ever worked or trained in. The inmate movement is structured and orderly. Operating under the principle of direct observation, officers are always present if inmates are out of their cells and physically interacting with staff or with each other. Inmates have clear and enforced guidelines of civility and cooperation. We consider our colleagues in the Department of Justice Services as partners that allow us to deliver health care in what is ultimately a very safe environment.

Annually, about 15,000 inmates stay in our facility for some length of time. During this time, most of our patients have the ability to access medical, mental health and dental care much faster than they would on the streets. While there are many acute situations — management of trauma, acute withdrawal conditions from legal and illegal substances, diagnosis and stabilization of serious mental illness, for example — we spend most of our time and energy in diagnosis, treatment and education regarding chronic illness.

We see the same major diagnoses as we would out in the community — hypertension, asthma, diabetes, dyslipidemia, back pain, sexually transmitted illness and the psychosocial overlays that color every life and condition. We have a window of opportunity to work with patients to help them take control of their health and manage their lives and their illnesses. For those who are ready to move forward, we can help by providing information about sliding-scale clinics in the community that they can access when released.

And we revel in incremental change — baby steps, when a patient takes them.

Of course, not everyone is ready. Many start using their substance(s) of abuse the moment they walk out of our doors. But many have come back to tell me stories of how they quit meth; and even though they are in on another DUI, at least they are clean of methamphetamines.

"That's something, isn't it?" they ask.

It certainly is.

But many patients break our hearts every time we see them back in jail. We have young males who grew up in the system and do not know how to function outside the structured environment of a correctional facility. We have the chronically mentally ill who are too sick to live on their own, but not sick enough for disability benefits or for permanent housing assistance. They are at their most stable when within our walls. And we have those who break the law just for treatment — a warm bed and three square meals a day.

From the standpoint of a medical practice, we have the same problems any practice faces: patients who don't take care of their health and don't stick to treatment regimens; unmotivated staff; burned-out staff and providers; administrative pressures; and working to stay ahead in a daily routine of putting out fires. But in correctional health care, the difference is that we are treating a population society usually keeps out of sight and mind.

A HEALING MINISTRY

Catholic health care should re-embrace correctional health care as ministry. This should be a no-brainer for providers, educators and mission leaders. We have a unique opportunity to broaden our mission, positively improve the health of individuals and community and train future providers to offer holistic and compassionate care. It gives us the means to step off of our manicured health campuses and back into the streets.

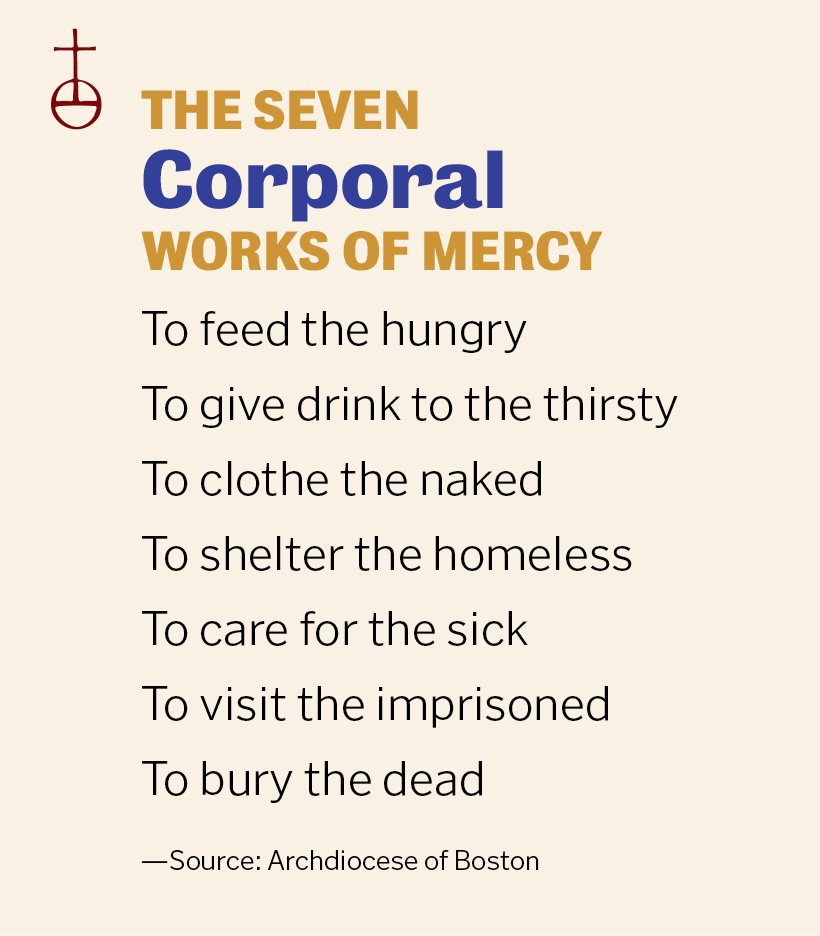

Correctional health care encompasses nearly all the corporal works of mercy, and many of the spiritual works of mercy as well. It is ministry. These are the people who were cared for by the saints and are visited by Pope Francis. We bring them pastoral care, but we can also bring them health care.

We have five Catholic schools of medicine and scores of residency programs in our country. We are responsible for training these learners in more than skills and procedures. We must teach them to heal. They must learn to appreciate their patients as whole human beings, with all the messiness that implies. In correctional health care, our patients are indeed messy — and they welcome our students, interns and residents.

Correctional health care can be a financially sustainable endeavor. Every county in the United States is responsible for the health care of its inmates. And, due to U.S. Supreme Court decisions in 1976 and 1980, all inmates are guaranteed a right to health care, including mental health care screenings as well as therapeutic care.

Most health care in U.S. correctional facilities is provided by publicly traded, investor-owned, for-profit corporations. But that is not the only model. We physicians of Saint Louis University provide family medicine and psychiatry services to the jail and juvenile detention program of St. Louis County, Mo. And St. Louis County pays its bills.

OPPORTUNITIES, LEADERSHIP

I just completed a two-day annual retreat with some of our medical students. The theme given to me was "Medicine as Vocation." The discussions during breaks and meals were characteristically all over the board. We spent a few hours talking about the changing role of physicians in health care.

This generation of upcoming physicians, the Millennials, have some unique assets to bring to the field of medicine: an appreciation of teamwork, a need for a broadly satisfying life and an idealism instilled in them by their Baby Boomer parents. They love my tales of correctional and community health, but they know they face an older generation of supervisors and systems that are slow to change. So, I encourage them to continue their reflective habits and utilize their assets in looking for consensus in their profession. All physicians are unique. But, all physicians have innate strengths and assets that can be recognized and cultivated to produce resiliency — particularly in this rapidly changing world of health care reform.

All physicians need resiliency. All physicians have teams of colleagues who support, direct and co-manage their days and their activities. All would benefit from a greater sense of gratitude and awareness to those who bring us success and effectiveness. All physicians enter into an intimate relationship with those they care for. All of us can find strength and purpose in reflection of this sacred trust, as well as an occasional visitation of why we went to medical school in the first place.

I love my work. The path here was and, on a daily basis, continues to be unpredictable and dynamic. But it is a path filled with contentment, gratitude and joy. Every single day, I remind myself I have learned something new. And every single day, I remember that my actions have helped at least one person gain understanding of his or her health.

Correctional health care is one means of further invigorating the ministry of Catholic health care. It also can inspire the providers who embrace this population. I hope that other physicians can sustain the joy and contentment in their work as I have in mine. And if they cannot do so on their own, perhaps they need to spend a little time behind bars.

FRED ROTTNEK is medical director of corrections medicine for the St. Louis County (Mo.) Department of Health. He is an associate professor and director of community medicine in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Saint Louis University. He also is a board member of the Criminal Justice Ministry and an advocate for re-entry programming to successfully transition ex-offenders back to the community.