BY: INDU SPUGNARDI

This edition of Health Progress covers many important topics related to palliative care — its connection to the mission of Catholic health care, efforts to define high-quality palliative care and the work of Catholic health care organizations to expand access to palliative care in the communities they serve.

While the number of palliative care programs is growing, this growth is tempered by:

- The way health care services are delivered and reimbursed

- A shortage of health care professionals who have the knowledge and skills to deliver high-quality palliative care, which encompasses symptom management, effective communication, psychosocial and spiritual support and care coordination

- A lack of research on the most effective ways to provide palliative and hospice care in a range of patient populations and settings

In Palliative Care: Transforming the Care of Serious Illness, Diane Meier, MD, a leading advocate for palliative care and a 2008 MacArthur Fellow, states, "… government and regulatory policy is required to bring the palliative care innovation to scale. Success will be achieved when all patients with advanced illness and their families can reliably access high-quality palliative care no matter where they live, what illness[es] they have, what their stage of disease, and where they need care."1

HOW PALLIATIVE CARE WORKS

Among the obstacles to palliative care access is confusion about what it means. Many people think palliative care is the same as hospice care, or they do not know what it is or when they might need it.

The National Quality Forum is an influential, not-for-profit organization that brings together a wide range of private- and public-sector stakeholders whose goal is to improve the quality of U.S. health care. The group defines palliative care as "patient- and family-centered care that optimizes quality of life by anticipating, preventing and treating suffering. Palliative care throughout the continuum of illness involves addressing physical, intellectual, emotional, social and spiritual needs and facilitating patient autonomy, access to information and choice."2

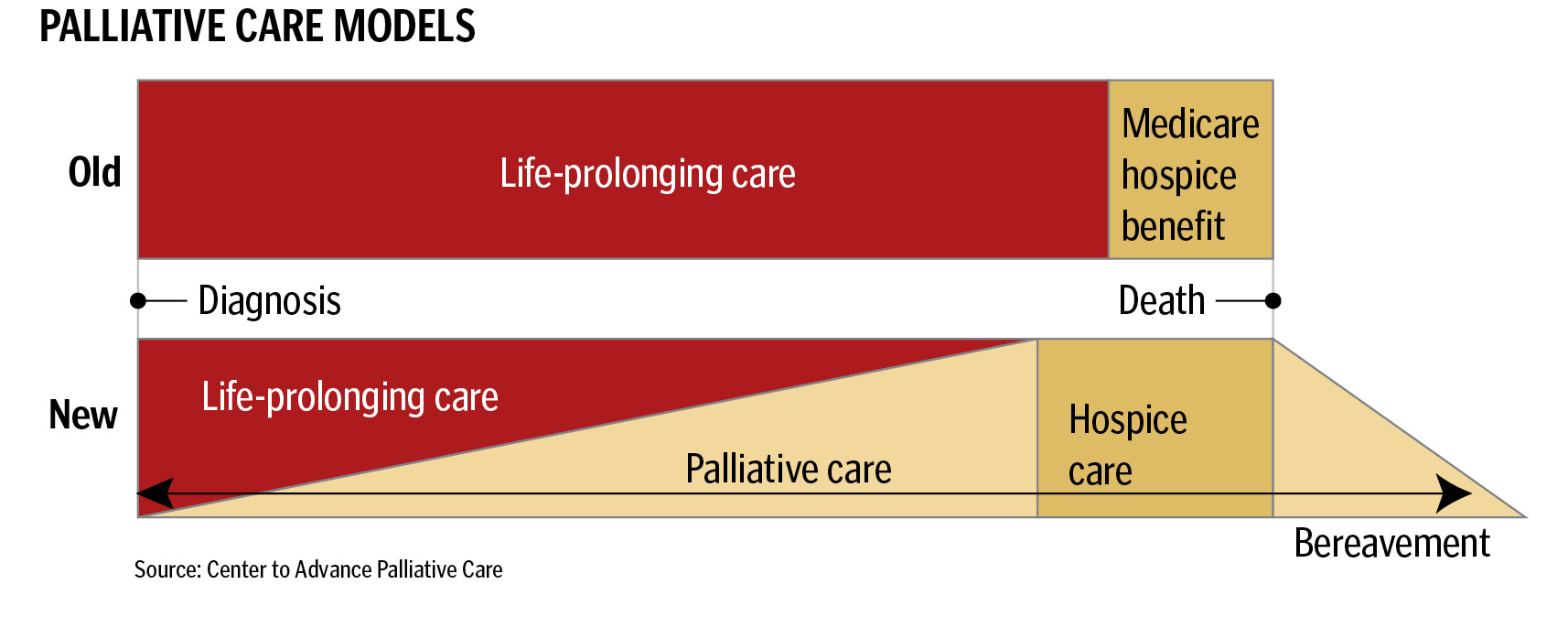

Palliative care is delivered at the same time as other curative and life-prolonging treatments, and it is not limited to the terminally ill. Hospice is a component of palliative care that is focused on the care of the terminally ill who have opted to stop curative, life-prolonging treatments.

The fundamental aspects of palliative care are communication and the coordination of care within and across various settings. An interdisciplinary team of health professionals who are skilled at holding the difficult conversations about the patient's illness, prognosis, treatment options and the realistic benefits and risks of those options is vital to effective communication. This team conducts a comprehensive patient and family assessment to understand and define goals of care and to learn what support is needed (such as monitoring and controlling levels of pain and other symptoms, or care needs in the home). These in-depth conversations help the team to support patient decision-making and to match treatments to patient goals.

The palliative care team also coordinates the care plan, which includes discussions with the patient, the family and other health care providers to ensure that all are on the same page in regard to the patient's condition, treatment options and how those options fit with the patient's goals.

Ideally, palliative care is introduced as soon as a person is diagnosed with a serious illness. The level of palliative care is tailored to the needs of the patient and the family. In the early stages of illness, palliative care interventions may be limited but they will increase as the disease progresses. Being involved at the outset allows the team an opportunity to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the patient's goals such as maintaining or improving function and optimizing quality of life, and to discuss the patient's condition and treatment options.

The diagram below contrasts the current standard of care with the palliative care approach.

MAKING THE CASE

Unfortunately, many people suffering from life-threatening illness do not receive palliative care. Patients and families struggle to control pain and other symptoms, to coordinate care among many different health care providers in many different settings and to obtain the information that can ensure treatments will reflect the patient's wishes. Far too often, patients at the end of their lives spend their final days in hospitals instead of in their homes surrounded by loved ones. During the patient's illness and after his or her death, caregivers and family members face many hardships and often don't receive support to overcome emotional and financial challenges.3

Research shows palliative care improves overall care for the seriously ill. Howard Gleckman's article in this issue of Health Progress discusses a study published Aug. 19, 2010, in the New England Journal of Medicine that finds providing early palliative care intervention for patients with lung cancer resulted in an improved quality of life, less aggressive interventions and longer survival than those receiving standard care. A journal editorial on the findings stated that the study represented an important step in confirming the benefit of providing palliative care and disease-specific treatment simultaneously at the point of diagnosis.4

A study published in 2008 in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society found similar results. The study was conducted with more than 500 family survivors of seriously ill veterans who had received inpatient or outpatient care in the last month of life from a participating Veterans Affairs Center. It assessed nine aspects of the care the patient received in his or her last month of life: the patient's well-being and dignity, adequacy of communication, respect for treatment preferences, emotional and spiritual support, management of symptoms, access to the inpatient facility of choice, care around the time of death, access to home care services and access to benefits and services after the patient's death.

The study found palliative consultations improve outcomes of care and indicated earlier consultations may confer additional benefit due to improvements in communication and emotional support.5

Palliative care has been shown to lower hospital costs by reducing both length of stay in the hospital and the intensive care unit and the use of costly diagnostic and therapeutic interventions of marginal or no benefit to patients.6 The reduction in cost can be attributed to enhanced communication, which is a key aspect of palliative care. In-depth, ongoing communication with their health care providers gives patients and families an informed and realistic understanding of their situation, the benefits and risks of various interventions and their impact on the patients' goals. This often, but not always, results in patient decisions to forgo aggressive treatments and to move to settings (home with hospice or out of the ICU) where they can receive care that is in keeping with their wishes.7

It is important to note that research has shown no difference in mortality or other adverse events associated with hospital palliative care. In the hospice setting, palliative care appears to be associated with both better survival and lower costs.8

BARRIERS TO PALLIATIVE CARE

Most palliative care advocates would agree that the biggest obstacle to the widespread availability of palliative care services is health care's current fee-for-service reimbursement system. This payment system does not compensate physicians adequately for the cognitive services — that is, the time spent in detailed communication — that are key to palliative care.

As Meier observes, these, the most fundamental palliative care services, are not reimbursed at all. "For example, the current Medicare payment system," she writes, "will not compensate physicians for the conduct of goals-of-care meetings with family members of seriously ill patients, whether in the hospital, in the office or at home. Nor will Medicare reimburse the necessary collaborative process of decision-making or the services of the interdisciplinary team required to deliver quality palliative care."9

Another major obstacle is the shortage of health professionals who possess the skills and knowledge to deliver high quality palliative care. America's Care of Serious Illness: A State by State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation's Hospitals, a 2008 report published by the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center, reports that in 2007, there were 2,883 physicians board-certified in palliative medicine (one physician per 31,000 persons living with serious and life-threatening illness.) Medical schools, nursing schools and schools of social work minimally cover palliative and end-of-life care in coursework and clinical clerkships, and this content is usually not required. The current payment system also indirectly adds to the shortage by providing greater reimbursement for services provided by acute care and specialty care practitioners and lower reimbursement for services provided by primary care and palliative care specialists. For young physicians with large student loans to pay off, the decision is often to go into one of the well-paying specialty or subspecialty fields.

Lack of sufficient research funding is another barrier. High quality palliative care depends upon research-tested delivery models that address a range of populations, diseases and care settings. Research is also needed to develop effective quality measures. These measures will be used to evaluate the quality of care, drive improvement and, eventually, determine payment as part of Medicare's value-based purchasing program. However, current research funding for palliative care is not meeting the needs of the field. A recent analysis of sources of funding for palliative care found that fewer than 5 percent of palliative care investigators received any National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding.10 At this time, a significant amount of funding comes from private sector philanthropic support.

THE AFFORDABLE CARE ACT

Provisions in the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed in March 2010 address some of these barriers. They include new payment and delivery models that could help promote palliative and hospice care, concurrent-care demonstration projects and funding for research on pain management.

Expanding coverage under Medicare or Medicaid to cover palliative care services is highly unlikely as the nation moves to implement the Affordable Care Act. However, new payment models being tested under the law, which include penalties for preventable readmissions, bundled payments, accountable care organizations and medical homes, won't be effective in improving care and reducing costs unless care is patient-centered and coordinated. Palliative care can help organizations achieve these goals for seriously ill patients, and, as a result, may become a more widely available benefit.

It is widely acknowledged that an obstacle to terminally ill patients gaining timely hospice care is Medicare's requirement to forgo curative treatment in order to qualify for the hospice benefit. The median length of time in hospice was slightly more than 20 days in 2008; more than a third of people died or were discharged from hospice in seven days or less.11 This last statistic is troubling to palliative care advocates because hospice benefits can provide crucial support for both patients and families during a very difficult time, and some research indicates they may extend the patient's life.12

The Affordable Care Act establishes a three-year "concurrent care" demonstration program at 15 sites nationwide, in which Medicare would cover both curative and hospice treatment simultaneously. The demonstration, scheduled to begin in 2012, will undergo an independent evaluation of its impact on patient care, quality of life and spending. Based on the results, the Secretary of Health and Human Services will recommend to Congress whether to change the hospice-care payment policy.

The Affordable Care Act also directs state Medicaid plans and state Children's Health Insurance programs (CHIP) operating as Medicare expansions immediately to cover concurrent care for children with terminal illnesses. States with stand-alone CHIPs are not required to cover hospice services, but if they do, they must now offer curative treatment concurrently.

Another area where advocates have called for more action is increased funding for palliative care research, specifically in the areas of pain and symptom management, health professional communication skills, care coordination and models of care delivery.

The Affordable Care Act authorizes an Institute of Medicine conference on pain care to evaluate the adequacy of pain assessment, treatment and management; identify and address barriers to appropriate pain care; increase awareness; and report to Congress on findings and recommendations by June 30, 2011. The act also authorizes the Pain Consortium at the NIH to enhance and coordinate clinical research on pain causes and treatments. It establishes a grant program to improve health professionals' ability to assess and appropriately treat pain.

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the provisions in the Affordable Care Act are a step in the right direction, other policy actions can accelerate needed changes. Meier outlines these actions in Transforming the Care of Serious Illness:

- Federal and private sector investment in a major social marketing campaign aimed at informing patients and families about palliative care and when to request it

- Legislation that will assure adequate NIH funding for palliative care

- Requirements by regulatory and accrediting bodies overseeing education of health professionals that schools commit to imparting palliative care skills and knowledge

- Federal and private sector actions to support palliative care education and fellowship training programs, including career development awards for junior faculty

- Medicare and other payers to create payment incentives for hospital- and provider-delivery of palliative care to appropriate patient populations. (This includes reimbursement for voluntary advance care planning)

- Public and private investment for the development and testing of clinical models for effective and efficient delivery of palliative care in all settings

At the state level, two significant policy efforts are worth noting.

- Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST), which allows persons with serious medical conditions to document their advance decisions for life-prolonging treatments as clear, specific, written medical orders that will be honored in all settings. To date, 14 states have adopted versions of POLST.

A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association finds that patients who used a standardized form signed by a physician to express their wishes for care at the end of life were more likely to receive their preferred level of care than patients who used more traditional methods such as advance directives and do-not-resuscitate orders.13 - Palliative care/end-of-life consultations. California and New York recently passed laws that would facilitate the discussion of end-of-life options between health providers and patients diagnosed with a terminal illness.

The New York law requires health care practitioners who are caring for patients diagnosed with a terminal illness to provide information and counseling regarding palliative care and end-of-life options, "including but not limited to: the range of options appropriate to the patient; the prognosis, risks and benefits of the various options; and the patient's legal rights to comprehensive pain and symptom management at the end of life." The information may be presented orally or in writing. Health care professionals must refer patients to another professionally qualified provider to discuss the information, if they do not wish to provide the information themselves.

The California law differs in that the health care provider has to provide the information on end-of-life options only if the patient requests it.

Because these are new laws, it will take some time to determine their impact on care for the seriously ill. Neither state's law offers reimbursement to health care providers for the discussions.

In an August 2010 Hospitalist News article, Wendy Edwards, MD, director of the palliative medicine program at New York City's Lenox Hill Hospital, commented that education would be a key component in the effectiveness of the legislation but there appeared to be no such formal requirements in the New York law.14 Advocates who worked to pass the legislation agree that provider education is key to ensuring that the conversations are effective. They hope that the law will prompt better end-of-life education in medical schools and professional training.

Although Edwards said she was not sure the new law was the best way to promote palliative care, she sees it as a positive development. "Palliative care won't just be the standard of care, but will be the law, which gives some backing to hospitals that seek to implement and strengthen their quality of care, and end-of-life care in particular," she said. However, passing a law will not make compliance easier for physicians who do not have experience in palliative care, she said. "It's a very hard discussion to have; it's not something doctors are trained to do."

CATHOLIC HEALTH CARE LEADS

The Center to Advance Palliative Care's 2008 analysis of hospital palliative care growth found that features commonly associated with hospitals that provide a palliative care consultation service included Catholic sponsorship.15

Compassionate care to all persons, especially to those who face serious illness, are in pain or are dying, has been a hallmark of Catholic health care. Such care is described in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, which reminds us that a primary purpose of health care "in caring for the dying is the relief of pain and the suffering caused by it. Effective management of pain in all its forms is critical in the appropriate care of the dying." Catholic health care's significant efforts to promote palliative care reflect this tradition.

The Supportive Care Coalition (www.supportivecarecoalition.org) is an important player in these efforts. The coalition, made up of 19 Catholic health care organizations (including the Catholic Health Association), assists Catholic health care organizations and their health care professionals to address the physical, emotional, psychosocial and spiritual needs of those suffering from life-threatening and/or chronic illness as well as those approaching the end of life. The coalition also advocates cultural and social policy changes so that all patients can experience living well until death.

INFORMING THE DEBATE

The policy changes outlined in this article range from short-term efforts (career development awards, increased NIH funding for palliative care research) to longer-term efforts (changes in the reimbursement system). However, in order for any of these efforts to be successful, the public and policymakers need to understand what palliative care is and how it benefits patients and their families.

During the health reform debate, opponents of reform focused on a provision in the House bill that would have allowed Medicare to reimburse physicians for voluntary, advance care-planning sessions. Opponents labeled these consultations "death panels." Even though the accusations were completely false, the negative reactions generated by the attacks doomed the provision, and it was stripped from the final legislation.

Misconceptions prevalent during the debate still linger. A July 2010 poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 36 percent of seniors said the health reform law "… allowed a government panel to make decisions about end-of-life care for people on Medicare," and another 17 percent said they didn't know whether the law authorized the government to make these decisions.16

As advocates, Catholic health care should take advantage of opportunities to inform their communities about palliative care and the benefits it provides to seriously ill patients and their families. As the population ages and our political environment becomes more polarized, these highly charged debates over end-of-life care are likely to take place again. We need to ensure that the public understands what is being debated and what is at stake if actions are not taken to improve care for the seriously ill and dying.

INDU SPUGNARDI is director, advocacy and resource development, Catholic Health Association, Washington, D.C.

NOTES

- Diane E. Meier, et. al., eds., Palliative Care: Transforming the Care of Serious Illness (Princeton: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010), 61.

- National Quality Forum, A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care: A Consensus Report (Washington, D.C.: National Quality Forum, 2006).

- National Priorities Partnership, National Priorities and Goals: Aligning Our Efforts to Transform America's Healthcare (Washington, D.C.: National Quality Forum, 2008).

- Amy S. Kelley, Diane E. Meier, "Palliative Care — A Shifting Paradigm," New England Journal of Medicine 363 (Aug. 19, 2010): 781-782.

- David Casarett et al., "Do Palliative Consultations Improve Patient Outcomes?" Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 56, no. 4 (2008): 593-599.

- Meier, Palliative Care, 57.

- Meier, 57.

- Meier, 57

- Meier, 54.

- Meier, 48.

- Michelle Andrews, "Medicare Will Experiment with Expansion of Hospice Coverage," Kaiser Health News (Sept. 7, 2010), www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Features/Insuring-Your-Health/medicare-hospice-coverage-expansion.aspx.

- Andrews.

- Bridget M. Kuehn, "End-of-Life Wishes," Journal of the American Medical Association 304, no. 8 (2010):846.

- Alicia Ault, "N.Y. Palliative Care Law May Not Change Practice," Hospitalist News (Sept. 9, 2010), www.ehospitalistnews.com/news/palliative-care-hospice/single-article/ny-palliative-care-law-may-not-change-practice/1d2265f54f.html.

- Center to Advance Palliative Care, "New Analysis Shows Hospitals Continue to Implement Palliative Care Programs at Rapid Pace" Press release (April 14, 2008), www.capc.org/news-and-events/releases/news-release-4-14-08.

- Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Tracking Poll (conducted July 8-13, 2010).