BY: ELIZABETH A. McCREA, Ph.D.

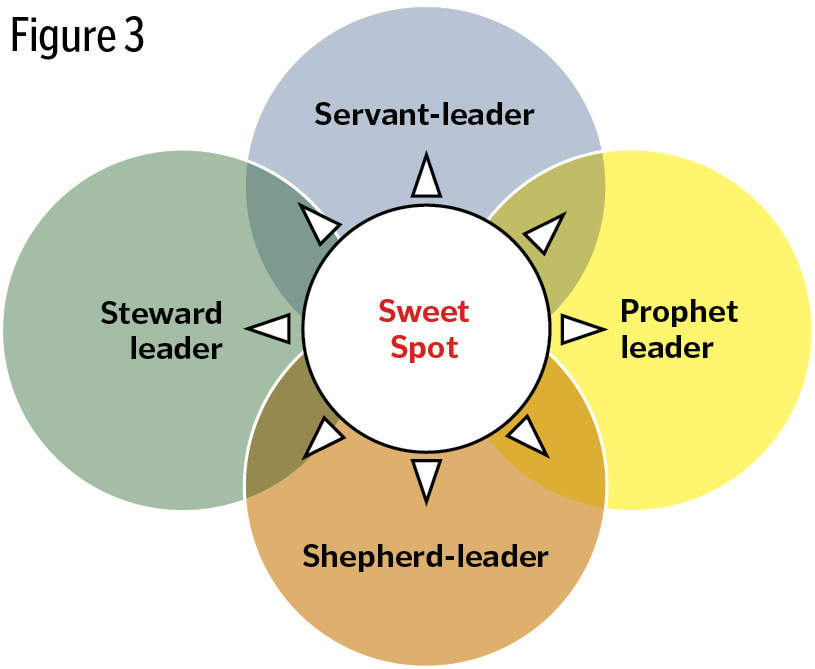

Successful Catholic health care executives are adept at switching hats, dealing with a ministry issue, then dealing with a leadership issue, as they navigate their day. However, true ministry leadership is like the sweet spot of a tennis racket: The power comes from the center, where all the interwoven strands come together. The question is, how do mission-driven organizations develop leaders who can confidently continue the healing ministry of Jesus as embodied by its founding religious communities while, at the same time, they are adapting and creating the resources needed to be successful in the rapidly evolving future of U.S. health care?

To address this question, Jfigudith Persichilli, RN, M.A., then president and chief executive officer of Newton Square, Pa.-based Catholic Health East (CHE), envisioned an in-house ministry leadership academy that would provide advanced ministry leadership formation and succession development for top-level executives, particularly lay leaders, with long-term career potential in the organization. (In April 2013, Persichilli was named interim president and CEO of the new ministry to be formed by CHE's consolidation with Trinity Health of Livonia, Mich. )

The academy's emphasis was not simply to develop executive leadership skills, nor was it simply to install an advanced ministry formation program. Instead the goal was to develop the participants' capacity to function in both worlds at the same time. In partnership with faculty from Seton Hall University, South Orange, N.J., executives from CHE began to develop an integrated curriculum that would give key executives an opportunity to further develop the critical ministry leadership characteristics, skills, knowledge and attitudes they would need to lead the Catholic health care organization now and in the uncertain, rapidly changing future.1

Inspired by the urgent need to support lay ministry leaders as they face a turbulent health care environment and to develop future top-level executives, the program's goal was to foster "contemplation in action"2 by blending knowledge and skill development with opportunities to reflect.

Negotiating this tension requires "ambidextrous" leaders who can adeptly handle the inherent conflicts between stability and change. They need "…capabilities for efficiency, consistency and reliability on the one hand, and experimentation, improvisation and luck on the other."3 Leaning too far towards preservation can lead to stagnation; however, leaning too far towards change can lead to chaos and waste. Indeed, recent empirical research in other fields has demonstrated that a balanced approach between exploring new options and leveraging current resources was positively correlated with success.4

We used the generalized empirical method developed by philosopher and theologian Fr. Bernard Lonergan, SJ, as a framework to loosely structure the program's six two-day sessions delivered over 18 months. The first cohort has completed the program, and surveys indicate that participants valued the face-to-face sessions and the intersession activities. Based on evaluative exercises, faculty judged that key concepts and attitudes were communicated. Further summative and formative evaluations are planned, even as a second cohort has been convened.

CURRICULUM DESIGN

Curriculum design started at CHE's top levels and included the executive vice president of mission integration, the vice president of leadership development and the vice president of mission and ethics. Since most of the candidates for the ministry leadership academy had participated in CHE's three-year ministry formation program, the curriculum needed to start where the initial formation program left off.

The goal, program designers agreed, was to help the participants integrate the core elements of ministry leadership into their policies, structures and organizational cultures such that Catholic identity explicitly informed the organization's daily operations and long-term vision. Such a goal required that managers understand Catholic social teachings, Biblical and theological understandings of relationships, personal and organizational integrity and the meaning of suffering and healing in the Catholic tradition, among other ministry knowledge and competencies.

The program also was to further explore and deepen participants' understanding of the charism of the organizations' founders; the role of Catholic identity and tradition in the organization; and the importance of health care ministry as embodied in the CHE mission.

But ministry alone would not be sufficient; the ministry leadership academy also would need to include the leadership skills required to guide a large and operationally diverse health care system that includes acute care hospitals, continuing-care retirement communities, home health/hospice agencies as well as long-term care, assisted living, behavioral health and rehabilitation facilities. Therefore, the CHE faculty also included in the program an operational leadership curriculum to help participants acquire an in-depth understanding and increased capability in defining, aligning and integrating core functions effectively throughout the organization. This dimension encompassed many traditional health care management concepts, including financial analysis, operational excellence, strategic thinking, marketing, informatics, health law, values-based decision-making and managing physician relations, but — and this is a critical point — viewed them all through a ministry lens.

Finally, the CHE team designed the transformational leadership portion of the curriculum so that it strengthened those skills essential to an organization's ongoing agility, innovation and growth. This section of the framework included the knowledge and skills needed for top managers to negotiate the challenging health care environment, such as creative thinking, community engagement, strategic change, talent development, organizational design, process improvement, conflict management and organizational agility, among several others.

DEVELOPING THE SWEET SPOT MODEL

Clearly a successful Catholic health care leader would need to balance these myriad leadership skills while simultaneously weaving mission-related principles throughout the organization's fabric. At this point, academics from Seton Hall University joined the process. CHE wanted a university partner to bring in fresh perspectives, new voices, subject-matter expertise and legitimacy for the program. The Seton Hall University faculty members came from a variety of schools, including representatives from the Graduate School of Health & Medical Sciences, the School of Theology, the School of Law, the School of Business, as well as the director of the Center for Catholic Studies. The goal of this larger faculty group was to create an integrated, university-based certificate program for the CHE Ministry Leadership Academy.

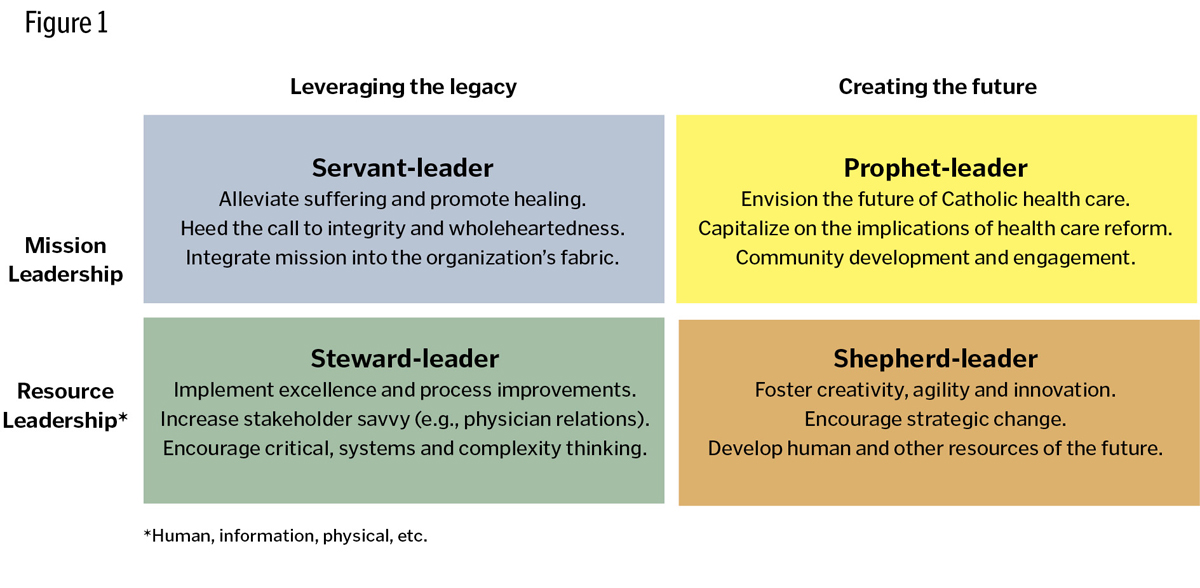

After discussing the myriad possibilities, a member of the team raised the concept of ambidexterity. What eventually emerged was a balanced model that highlighted the ambidextrous nature of leadership in any modern organization, along with a deep appreciation of a Catholic health care organization's mission. The resulting model is a two-by-two matrix; it visually conveys the need for balance, both along the dimensions of leveraging the legacy versus creating the future, and the equally important dimensions of resources versus mission.

Servant-Leader: Mission is central to CHE's culture. A servant-leader goes beyond simply preserving the founders' healing ministry to leveraging or "living" the mission of Catholic health care. In this case,

Servant-Leader: Mission is central to CHE's culture. A servant-leader goes beyond simply preserving the founders' healing ministry to leveraging or "living" the mission of Catholic health care. In this case,

… a servant-leader focuses primarily on the growth and well-being of people and the communities to which they belong. While traditional leadership generally involves the accumulation and exercise of power by one at the "top of the pyramid," servant leadership is different. The servant-leader shares power, puts the needs of others first and helps people develop and perform as highly as possible.5

CHE's various institutions have strong traditions of alleviating suffering and promoting healing, especially among the poor and disadvantaged. The religious congregations who founded the component ministries of CHE believed deeply in acting with integrity and wholeheartedness, with a focus on the dignity of the persons served, and serving those less fortunate. In addition, they integrated this calling and their healing mission into the very fabric of their organizations. It is incumbent upon future lay leaders to preserve this legacy, even as the organization adapts to the ever-changing health care environment.

Prophet-Leader: This describes roles central to the evolution of the organization's healing mission. A prophet-leader envisions the future of Catholic health care, especially in light of the increasing reliance on lay leaders, recent health care reform in the United States, advancing health care technologies like genomics, non-embryonic stem cells, electronic medical records and other issues. Catholic health care leaders today have to navigate changes that were unimaginable just a few years ago, including mergers or alliances with non-Catholic organizations.

The role of prophet also encompasses the important work of community development and engagement. To carry on the religious founders' original vision, senior CHE executives must spread the word about the unique value of a Catholic approach to health care and adapt it and shape it in ways that are relevant to today's communities. Prophet-leaders need to find creative ways to stay solvent so CHE can continue to minister to the poor and disadvantaged and to maintain a person-centered focus throughout the institution. These executives must also advocate for the evolving nature of the Catholic health care ministry in many diverse arenas, including local communities, local, state and federal governments, the church and among other faith-based and secular organizations.

Shepherd-Leader: This term focuses on the roles needed to lead the organization to "green pastures."The shepherd-leader creates the kinds of resources — human, physical, informational, etc. — needed to be successful in the future. Leaders operating in this realm are called to foster creativity and innovation among their followers in a very challenging environment, especially since not much is known about the kinds of resources that will be necessary as the future unfolds. This will require the leader to identify and find cutting-edge resources, and to create an agile organization able to integrate and leverage these new assets.

Key to this endeavor is the shepherd-leader's ability to develop well-rounded lay leaders imbued with the ability to create the future of Catholic health care. Executives need to absorb the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in today's health care environment so they may lead their organizations to "calm waters" — or at least to avoid the most turbulence. By ensuring the success of their followers, shepherd-leaders will foster the future success of the organization as a whole.

Steward-Leader: This term encompasses the wise use of the organization's current resource base. The leader operating in this arena needs to implement best practices in excellence and process improvements, like Total Quality Management. They need to build strong relationships with physicians and other stakeholders who provide critical resources to the organization so that it can operate efficiently and effectively. Steward-leaders also need to encourage critical, systems and complexity thinking to ensure that CHE extracts the most value possible from every available resource.

TENSIONS AND PARADOXES

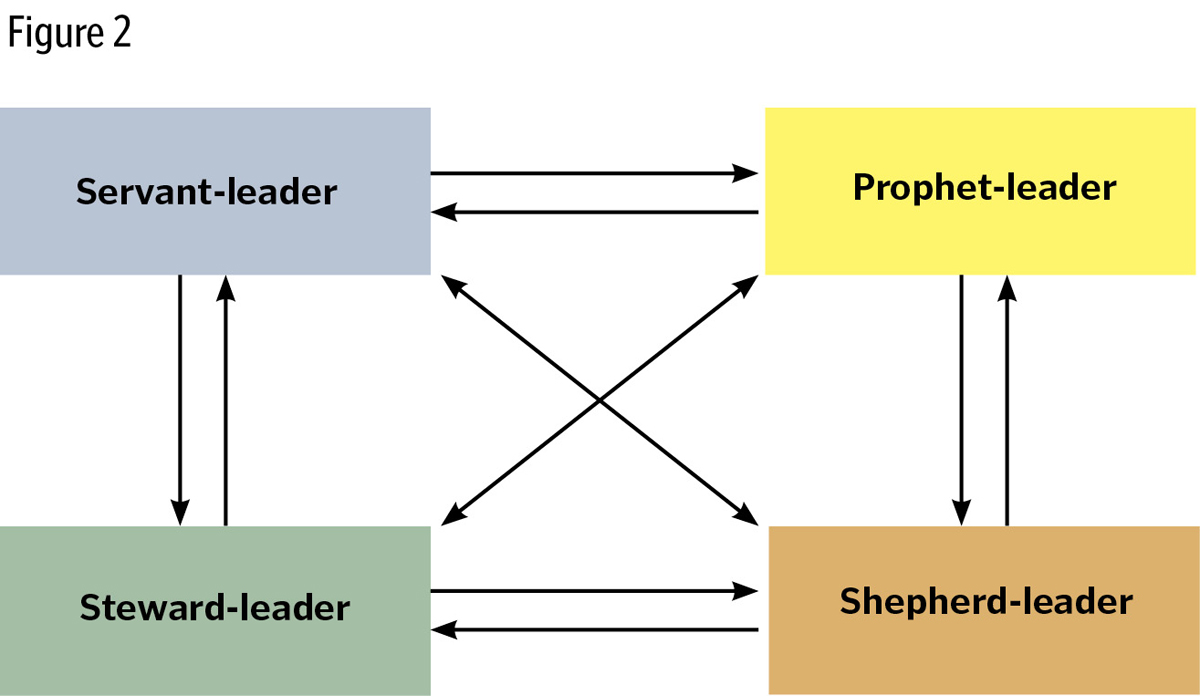

Though the matrix captured both the complexity and the balanced nature of Catholic health care ministry leadership in CHE, it did not seem to emphasize sufficiently the system tensions inherent in an ambidextrous organization. For example, Andriopoulos and Lewis6 (2010) found that firms had to develop methods of negotiating the paradoxes in the innovation process, particularly long-term adaptability against short-term survival; possibilities versus constraints; diversity as opposed to cohesiveness; and passion versus discipline. The team felt this concept of negotiating opposing tensions was so important — especially to the development of ministry leaders — that they developed a systems model to depict the influences and tensions faced by Catholic health care leaders as they negotiate the tensions between servant-, prophet-, shepherd-and steward-leadership roles.

For example, if ministry leaders invest too much of themselves in their steward-leader role — as many midlevel managers in organizations do — they will likely neglect their roles as shepherd, prophet and servant, which will push the entire system off-kilter. As He and Wong observed, there is a "need for managers to manage the tension between exploration and exploitation on a continuous basis."7

THE SWEET SPOT

There was still, however, an element of dissatisfaction with the two models. Although the first model depicted the need for senior managers to be ambidextrous, and the second highlighted the need to negotiate the dynamic tensions inherent in health care leadership roles, neither model captured the need for managers to develop what He & Wong called "a 'synthesizing capability' to create competitive advantage out of conflicting forces."8

Clearly health care ministry leaders need to simultaneously enact all of the leadership roles. In a manner similar to the relationship between yin-yang in Chinese philosophy, ministry leaders must embody both good leadership and good ministry practices at the same time. Perhaps they may have to emphasize one role over the others in particular situations, but over time, all roles need to be fully involved and fully integrated. The team created a diagram to harmonize with the other two models, which we named the "Sweet Spot."

In the end, we determined that the phenomenon of ministry leadership is too complex to depict easily using one single model. Thus the academy uses all three frameworks at different points in the program, generating more discussion and more insight than the use of any one model would have likely achieved.

Each version of the model looks at the same ministerial leadership phenomena, using the same four elements (servant-, steward-, shepherd- and prophet-leadership), but emphasizes a different dynamic: balance, system tensions and synthesis. All three dynamics appear to be important — in the eyes of both the practitioners and the scholars — to the effective leadership of an organization that must simultaneously create the future while leveraging, preserving and adapting the legacy of its healing ministry. Most importantly, it provides a framework and a vocabulary for ministry leaders to use as they make the decisions that will lead their organizations forward.

ELIZABETH A. MCCREA is assistant professor of management, Stillman School of Business, Seton Hall University, South Orange, N.J.

NOTES

- The models presented here represent a collaborative effort. From Catholic Health East, the codevelopers were: Sr. Julie Casey, IHM, the former executive vice president of mission integration; Sr. Mary Persico, IHM, executive vice president of mission integration; Anita Jensen, Ph.D., vice president of leadership development; Phillip Boyle, Ph.D., vice president of mission and ethics. From Seton Hall University, the codevelopers were: Monsignor Richard Liddy, Ph.D., professor and Director of Catholic Studies; Zeni Fox, Ph.D.,professor of seminary instruction; Terrence Cahill, Ed.D.,associate professor and chair, Department of Graduate Programs in Health Studies; Elizabeth McCrea, Ph.D., assistant professor of management and entrepreneurship.

- John W. Glaser and Deborah A. Proctor, "Keeping Formation In-House Deepens Catholic Culture," Health Progress 92, no. 5 (September-October 2011): 26-31.

- Michael L. Tushman and Charles A. O'Reilly, "Building Ambidextrous Organizations: Forming Your Own 'Skunk Works,'" Health Forum Journal 42, no. 2 (1999): 20.

- Angeloantonio Russo and Clodia Vurro, "Cross-boundary Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in the Fuel Cell Industry," European Management Review 7, no. 1 (2010): 30-45.

- Robert K. Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership, https://www.greenleaf.org/what-is-servant-leadership/.

- Constantine Andriopoulos and Marianne W. Lewis, "Managing Innovation Paradoxes: Ambidexterity Lessons from Leading Product Design Companies," Long Range Planning 43, no. 1 (February 2010): 104.

- Zi-Lin He and Poh-Kam Wong, "Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis," Organization Science 15, no. 4 (July-August 2004): 481.

- He and Wong, "Exploration vs. Exploitation."

BERNARD LONERGAN AND CATHOLIC HEALTH CARE

By MONSIGNOR RICHARD M. LIDDY, Ph.D.

Helen Keller (1880-1968) grew up unable to see or to hear, cut off from the world, helpless and dependent. One day in March, 1887, her teacher, Anne Sullivan, took her for a walk, and Keller describes the scene in her autobiography, The Story of My Life:

We walked down the path to the well-house, attracted by the fragrance of the honeysuckle with which it was covered. Someone was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout. As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word w-a-t-e-r, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motion of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew that w-a-t-e-r meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. That living word awakened my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free! … I left the well-house eager to learn. Everything had a name and each name gave birth to a new thought. As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life.

For the Canadian Jesuit philosopher-theologian Bernard Lonergan (1904-1984), it was not just the discovery of language that was important, but the discovery of discovery itself: the act of insight, of understanding, of that "aha!" moment at the core of Helen Keller becoming such a significant leader. For what is authentic leadership but understanding the situation and what needs to be done, and communicating that vision to others?

Much of Lonergan's work consisted in inviting people to come to understand the preconditions for understanding — for example, as in Helen Keller's case, experiencing, attending, questioning, imagining — as well as all that follows from understanding, such as formulating in symbols or words, reflecting, judging, evaluating, deciding, acting, loving, etc. Lonergan found in close attention to these conscious acts a pattern of drives towards authenticitythat are evident in sophisticated ways in the lives of heroes and saints; in the methods of scientists and scholars; and in such ordinary examples as Helen Keller's discovery of the miracle of language. This pattern of conscious experiences presupposing and complementing one another — which anyone can discover in themselves — provides for Lonergan the basis for a nonmaterialist and empirically verifiable philosophy of the human person open to the world, as well as to the question of God. As he wrote in his 1957 work, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding: "Thoroughly understand what it is to understand, and not only will you understand the broad lines of all there is to be understood but also you will possess a fixed base, an invariant pattern, opening upon all further developments of understanding."

At this point, one could rightly ask: So what? Why seek an interdisciplinary language?Catholic Health East's collaboration with Seton Hall University in the Ministry Leadership Academy provides a case in point. The aim of the academy is to help leaders to become "ambidextrous," that is, to be able to shift from one mode of leadership to another as the occasion demands: from steward to servant, from shepherd to prophet. Beneath the different dimensions of leadership, there are different competencies successively invoked — and at the core of all these competencies is correct understanding of what precisely is needed in this or that situation.

The sessions of the Ministry Leadership Academy, based on Lonergan's method, have been structured around what he calls the transcendental imperatives: Be attentive! Be intelligent! Be reasonable! Be responsible! Be loving! And if necessary, change! For, as Helen Keller, we ourselves are built to be attentive to the data, to seek its meaning, to reflect on whether it's just a bright idea or in fact the truth, and to evaluate options for decisions aimed at the genuinely good. As one of the academy participants wrote:

The concept that has really impressed me over the past week is "the search for meaning." Even more intriguing is the notion that meanings change. I spend a significant part of my day asking questions, understanding answers and searching for the meaning of the answers. Most of the time, I'm trying to correlate answers to similar questions, to see if there are trends or correlations that may have a broader meaning. The recognition that meanings change, means that the correlations and conclusions are subject to modification and invalidation. Inquiry and judgment, therefore, require constant vigilance and reflection.

The core of "ambidextrous" ministerial leadership in changing times is the ability to understand, to check one's understanding — is it just a bright idea? — to recognize one's own biases and those of one's culture,to act and "create the change one wishes to see" and, on the basis of feedback from the new situation, to begin again the process of experiencing, understanding, judging and deciding.

In a time of turbulence when ambidextrous leaders are needed, Lonergan provides a vision of the person as open to the Spirit of God healing our darkness and aiding us to be concretely attentive, questioning, reflecting, evaluating, loving — eventually beginning the cycle all over again from a new spot — as evidently Helen Keller did.

MONSIGNOR RICHARD M. LIDDY is director of the Center for Catholic Studies at Seton Hall University, South Orange, N.J.

READINGS

For the link between Lonergan and the Catholic intellectual tradition, see Richard Liddy, Transforming Light: Intellectual Conversion in the Early Lonergan (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1993); for a story of "catching on" to Lonergan's thought: A Startling Strangeness: Reading Lonergan's Insight, (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2007). For a very good introduction to Lonergan's basic philosophy, see Brian Cronin's Foundations of Philosophy: Lonergan's Cognitional Theory and Epistemology (Nairobi: Consolata Institute of Philosophy Press, 2005).

MINISTRY LEADERSHIP ACADEMY

In April 2011, Judith Persichilli, R.N., president and CEO of Catholic Health East (CHE), welcomed the Ministry Leadership Academy's first class by acknowledging the strengths and contributions of each individual participant and outlining her vision for his or her personal future in the organization.

The cohort, a mix of about 20 system office and facility leaders, met for two-day sessions at a conference center for a total of six retreats, spread out over 18 months. The group divided into different breakout teams for each session so all the participants could get to know each other. The eight faculty from Seton Hall and the system office sat at tables with the teams so they could both facilitate and participate in the activities, following the "guide on the side" rather than the "sage on the stage" teaching approach.

Each day had a theme and began with a focusing point such as a story, a Bible passage or a film clip to invite reflection on the topic. The participants then embarked on a series of short lectures, reflective exercises, journal writing, meditations and skill-building sessions. After a closing prayer, the first day of each two-day session ended with a team-building activity and a communal dinner. Most participants stayed at the conference center overnight, and the second day followed a similar pattern: opening prayer and reflection, session lectures and activities and concluding reflection.

The session themes were based loosely on the stages of the Canadian Jesuit theologian and philosopher Bernard Lonergan's Generalized Empirical Method (see page 75). The faculty tried to build each two-day session in a "just-in-time" fashion, so that the sessions reflected the main issues facing the organization at the time. Titles of some of the topics: "Grace: What It Is and Why It Matters," "Interacting with the Church," "CEO Sense-making," "Sponsors' Understanding of Church and Their Expectations," "Catholic Identity," "Creative Power," "Organization in the Mind," "Leading in Chaos," and "Understanding Organization Design for Strategy Execution."

During each session, participants had time to apply the course material to their own situations at work through reflection, journaling and discussion. Several times over the course of the program, the faculty referred back to the "Sweet Spot" model to encourage participants to integrate leadership and ministry, as well as to leverage the legacy and create the future in their work.

Most sessions featured guest speakers, a wide-ranging group who were invited to share their expertise with the cohort. Among them: Sr. Carol Keehan, DC; president and CEO of the Catholic Health Association; Andre Delbecq, D.B.A., the J. Thomas and Kathleen L. McCarthy University Professor at Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, Calif., and a member of Ascension Health's board of trustees; J. Michael Stebbins, Ph.D., senior vice president of mission services, Avera Health, Sioux Falls, S.D.;Rev. John Haughey, SJ, senior research fellow, Woodstock Theological Center at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.; and John Allen, senior correspondent for the National Catholic Reporter and senior Vatican analyst for CNN.

During their time between the face-to-face sessions at the conference center, the participants engaged in various readings and reflections. Each person was able to custom-tailor the intersession activities to his or her own needs. In addition, the faculty provided one-on-one mentoring, leadership assessment and enrichment experiences to address development areas.

At the concluding session, the participants spent time reflecting on the Ministry Leadership Academy journey, synthesizing what they learned and mapping out their continued "sweet spot" development. In a closing ceremony, participants received their Certificates in Ministry Leadership from Seton Hall University.

— Elizabeth A. McCrea, Ph.D.