By BETSY TAYLOR

An emergency medicine doctor rushes to stabilize a gunshot victim in a Chicagoland emergency room. It is a scene that may play out dozens of times across the city and near suburbs on an overheated and turbulent night.

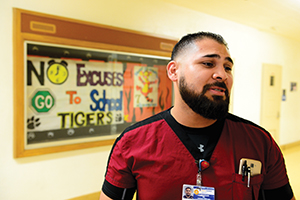

An intensive care unit nurse working in a suburban Los Angeles hospital sees his younger self in teens growing up in gang-ridden neighborhoods; he volunteers to visit their schools and proposes they might become hospital employees, rather than hospital patients, by making thoughtful, deliberate choices today.

Christian Diance, an intensive care nurse from Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in suburban Los Angeles, visits San Fernando Senior High School in California on April 5 to talk to teens about making responsible choices. His community outreach is aimed at preventing gun violence and trauma injuries resulting from bad decisions.

Photo by Dean Musgrove/Los Angeles Daily News

The manager of diagnostics imaging services at a West Baltimore hospital will not allow herself to become numb to the damage wrought by gun violence. A mother herself, she aches for parents who bury their sons and daughters, felled by a culture of violence. She organizes events to build bridges between police and area youth to curb violence on the streets.

Individuals working in urban hospitals, especially those with trauma units, recognize gun violence as an acute public health crisis. In an age where political polarization has deadlocked many efforts to advance public policy solutions, some individuals are doing what they can in their communities to break the cycle of violence.

The doctor, the diagnostics manager and the nurse each have a slightly different approach to community outreach to end gun violence or mitigate its damage, but all subscribe to the adage "to save a life is to save the world." They believe that individual actions and efforts by health systems and hospitals can reduce gun deaths.

Every day, about 315 people in America are shot. This includes murders, assaults, suicides and suicide attempts, unintentional shootings and police actions. Every day, about 93 people die from gun violence, including 32 murders — most of the gun deaths are suicides. That's according to an analysis from the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit promoting stronger gun laws, including broader requirements for background checks on gun purchasers.

'Everyone's blood is red'

One of the hardest hit cities is Chicago, where gun violence is an ongoing plague. By early July, the city had registered 346 murders for the year, the majority of them shooting deaths. Loyola University Medical Center is in Maywood, Ill., just outside Chicago. It operates a Level 1 trauma center, and its emergency room staff frequently work in high stress situations where life or death hang in the balance.

Marie Coglianese, Loyola University Health System's director of spiritual care and education, and chaplain Bob Andorka blessed the emergency department, its staff and patients in early June, praying for peace in the community and for protection from violence, including gun violence. Employees, who routinely work to save the lives of gunshot victims, wore orange ribbons as a show of their support for advocacy against gun violence.

"Regardless of one's shape, color, sex or ZIP code, inside everyone's blood is red and too much of it is spilling on our streets." That's from an opinion piece penned for the Chicago Tribune last year by Dr. Mark Cichon, Loyola University Medical Center's emergency medical services director, and the Rev. Michael Hayes, one of the medical center's chaplains. They said gun violence needs to be addressed as a public health epidemic like the Zika virus, cancer, heart disease or obesity.

Aftercare

The medical center's staff, chaplains, social workers and case managers are fostering new relationships in Chicago area neighborhoods, so that when they talk to a patient recovering from a gunshot, or to a patient's loved one, they can connect that person directly to a pastor or social services organization that can assist with their needs when the gunshot patient returns home, or the family is left to grieve.

Rev. Hayes attends Proviso Township meetings in Cook County to scout for community activist ministers and agencies willing to be a resource to Loyola patients, including gunshot patients and their families, once they leave the hospital.

Coglianese said Loyola is sounding out pastors to see if there would be an interest in learning about the effects of violence and providing pastoral care to those who have experienced it; the hospital also is looking into beginning a support group or retreat for mothers who have experienced the death or injury of a family member due to gun violence. "We're not saying here's the formula to make you feel better," she said. "We're asking, 'What would be helpful to you?"'

Offering hope

Christian Diance grew up in a rough section of Pacoima, in Los Angeles. Raised in a supportive family, he stayed focused in school and on his future and now works as an intensive care nurse at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills in suburban Los Angeles. He has about one patient a week who has a life threatening gunshot injury. And he's seen his share of young accident victims too.

Together with two clinical colleagues, he volunteers to talk to kids about decisions that can lead to violence and trauma.

Their presentation at schools includes videos of surgeries. Students see blunt force injuries caused by a texting driver and what bullets do to bodies. "Teenagers think they're invincible. It's a reality check," Diance said.

Diance talks to them about how he stayed out of trouble as a teenager, though he grew up in an area with gang activity. He spent a lot of time playing organized sports. He tells them about the steps he took to become an intensive care nurse and lets the teens know a medical career is possible for them.

The health care providers give their emails in case students have follow-up questions. "When I'm at schools talking to kids, I have in the back of my mind the trauma patients I've treated," Diance said.

Clark

Fighting crime and grime

At Bon Secours Baltimore Health System, staff from the Community Works outreach center have temporarily suspended door-to-door canvassing to tell neighborhood residents about community and social services at the outreach center. After a couple of shootings in the vicinity of Bon Secours Hospital, which is a few blocks away from Community Works, employees don't feel safe walking the neighborhood, said Curtis Clark, vice president of mission for Bon Secours Baltimore.

The health care system invites the community in, hosting "Crime and Grime" meetings at Community Works. Representatives from the hospital, the Baltimore police department and neighborhood associations share information about where violence is particularly bad at the moment, areas of improvement and what they're working on in the short term and long term to make the neighborhood safer.

Carolyn Greene, a manager at Bon Secours Hospital, spent time at a trauma center in Baltimore this year with a relative who was being treated for injuries following a scooter accident. Greene recalled at least two young people who were brought into the trauma center after being shot. She wants young people to be able to realize their potential, and knows a shooting shatters someone's future in an instant. "There is a light that just dims so fast. It's so sad. These kids look like they could be my babies. What can I do for the next babies coming up?"

Greene

With backing from Bon Secours Baltimore, she helped organize a one-hour gun buyback program with the Baltimore Police Department last year; it was intended as a trial run to gauge community response. Seven guns, including two rifles, were turned in. Bon Secours employees used some of the proceeds from a crab feast to buy back the weapons.

Greene and Capt. Jeffrey Shorter of the Baltimore Police Department are working to involve the police in more events offered by the hospital, including its annual Community Day, where free health screenings are available. They are planning to invite them to neighborhood movie nights and a "Snowball with a Cop" event, where young people will get free snow cones.

Greene said it's important for police and young people to have an opportunity to build ties and mutual trust.

Marie Coglianese, Loyola University Health System's director of spiritual care and education, shown here second from left, offers a prayer for peace and for all those affected by gun violence, on June 7 in the emergency department at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill.

Clark said Community Works has offerings that directly assist people trying to improve their lives, including a "redirection" program where teenage participants are under court mandates to complete a 10-week program to provide them with social, life and job skills. A separate six-month job training program gives other young people an alternative to selling drugs and other criminal pursuits.

Work to help young people gain employment and life skills can provide them with options and ultimately help reduce gun violence, Clark said.

Bon Secours is part of an effort to fund the construction of a $3.8 million youth development center in the neighborhood.

Hospitals need to heal outside their walls, Clark said. "We don't think being a health care system means — hey, that's not our job, or that's law enforcement's job." Of gun violence, he said, "It's something we feel obligated to figure out, we do."