By JULIE MINDA

NEW YORK and RHINEBECK, N.Y. — In the 1970s and 1980s, relatively little was known about Huntington's disease. So, when the normally loving and gentle Jim White started becoming increasingly angry and argumentative — and at times combative — his wife and six children were perplexed.

And when White, then in his 40s and highly successful as a pharmaceutical salesperson, began missing appointments and his work performance began to slip, the gossips said he must be an alcoholic.

After years of physical and mental decline and several misdiagnoses — including male menopause and stress — White received the correct diagnosis in 1981 from a family friend and physician. It was devastating. White had Huntington's disease.

Mary White Moore and Tom White, two of White's children, were in their 20s when their father's mental deterioration became pronounced. Mary White Moore says the family "lived with the horrors of HD." Tom White says as their father's condition worsened, he needed around-the-clock care and, eventually, required help with every activity. Every member of the White family — along with a patchwork of close friends and family and hired aides — pitched in to try to keep Jim White safe, fed, bathed and to dress him as he slowly lost his ability to walk, eat and communicate.

"The years prior to diagnosis were especially dark and frightening as my parents in particular and all of us struggled to figure out what was happening around us," Tom White recalls.

It is because of Jim White that Catholic provider ArchCare established facilities offering specialized care to people with Huntington's disease. While about 30,000 people in the U.S. today have received a Huntington's disease diagnosis, there are fewer than 300 beds in long-term care facilities nationwide dedicated specifically to their care.

New York City-based ArchCare has 48 such beds in a unit at its Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center in New York City's East Harlem neighborhood, and 38 are in a unit at its ArchCare at Ferncliff Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center in Rhinebeck, N.Y. Rhinebeck is about 100 miles north of New York City. ArchCare is a continuing care provider run by the Archdiocese of New York.

New choice

The ArchCare units were the inspiration of Cardinal John Joseph O'Connor, archbishop of New York from 1984 until his death in 2000. Cardinal O'Connor became friends with Jim White and his wife Mary a few years after White was diagnosed with Huntington's.

The cardinal visited their home during the late stages of Jim's illness and saw Mary and her six children struggle to care for Jim there. Struck by his friends' plight, the cardinal tasked the Terence Cardinal Cooke nursing home with establishing the nation's first Huntington's disease residential unit. It opened in 1988, and Jim White was its first resident and lived there until his 1998 death.

The unit expanded a decade later and, in 2004, it was dubbed the Mary and Jim White Unit for the Care of People with Huntington's Disease. Eleven years later, ArchCare opened the second unit at its nursing home in Rhinebeck.

One of Mary and Tom White's siblings, Liz, also had Huntington's disease; she lived at the ArchCare unit in Harlem for several years before her death in 2006. Cousins of Mary and Tom White currently reside at ArchCare units. The White family have been key supporters of ArchCare's Huntington's facilities.

Defective gene

Huntington's disease is a progressive degenerative brain disorder caused by a defective gene. That gene codes a "blueprint" that continually copies a defective protein causing a breakdown of nerve cells in the brain. Most but not all people with the condition begin experiencing symptoms in the prime of life between the ages 30 and 50. Children of a parent with the condition have a 50-50 chance of inheriting the defective gene.

People with Huntington's typically exhibit chorea, or involuntary, uncontrolled movement of the arms, legs, head or other body parts, as well as a decline in physical ability. The disease usually brings about a progressive decline in thinking and reasoning ability, including a loss of memory, concentration, judgment and planning skills. The condition is associated with mood disorders, especially depression, anxiety, anger and irritability.

According to the Huntington's Disease Society of America, the disease presents subtly at first, but symptoms and loss of mental and physical function worsen over its trajectory of 10 to 20 years, on average. In the late stages of the condition, a person may lose the ability to walk and speak, and become entirely dependent on others for care.

There is no cure for Huntington's disease, and no way to slow or stop the brain changes it causes, according to the Huntington's disease society. Treatment normally includes drugs and therapies to manage symptoms.

Few options

Alicia O'Keefe, program coordinator for the Center for Neurodegenerative Care at Ferncliff, says that when people with Huntington's no longer can live safely in their own homes, they often find it extremely difficult to find a place to live. Usually, when people with mid- to late-stage Huntington's disease are able to find a placement, it is in a nursing home or, particularly for people exhibiting aggression, a psychiatric unit. However, such placements often are not ideal because at most nursing homes and psychiatric units, the staff — while likely well-meaning — do not usually have the training or time to provide optimal care for people with Huntington's disease, says O'Keefe.

O'Keefe says it takes specialized training to care for people in the mid to late stages of Huntington's disease because the caregivers must understand the particulars of the disease, how symptoms present, interventions and therapies available to manage those symptoms and how to communicate with the person as his or her speech becomes difficult to understand — a commonality with the condition.

Because of the chorea, falls, injuries and choking are all persistent risks; and so staff also must understand how to mitigate those and other dangers, O'Keefe says. For instance, staff learn specifically how to interpret the unsteady gait of a person with Huntington's so they know precisely when to assist — and when to allow the person to continue moving.

Enhanced staff-to-resident ratios are needed for residents with Huntington's, since those in the late stage of the condition need individual assistance with the activities of daily living including eating. O'Keefe says staff listen for coughing in the dining room, which could be an indication a resident needs thickening fluids in a drink, or for solid foods to be chopped up smaller or pureed.

Specialized training

At both the New York City and Rhinebeck units, the medical director is a physician specializing in degenerative neurological conditions; and all staff on the units — including nurses, aides, therapists, social workers, housekeeping staff and maintenance workers — receive training on Huntington's disease and on other degenerative brain disorders.

The medical directors provide this specialized training to new staff on the units. Plus, the facility offers monthly training — some of it required and some voluntary — on such subjects as behavioral interventions, therapies and medications for people with Huntington's disease.

Charissa Brown is program manager of the New York City unit; and Amina Mamah is a clerk on that unit. Brown says both ArchCare Huntington's facilities have more staff per resident than is typical in a nursing home.

Engagement

Brown, O'Keefe and Mamah say staff on the units get to know residents as individuals and stay abreast of each resident's individualized care plan for a better understanding of the therapies, interventions and pharmacopeia that could include antipsychotics, antidepressants, antianxiety drugs and drugs to calm the body tremors. Staff try to minimize the use of chemical sedation to calm agitated patients, and they do not use physical restraints, says O'Keefe.

Both units offer numerous and frequent activities tailored to their residents' abilities, including games, arts and crafts, horticulture and exercise programs. Caregivers say activity is important for maintaining mental engagement. The activity also helps minimize behavioral issues.

Mamah, a 27-year employee who is believed to be the first staff member hired for the Huntington's unit in New York City, says years of experience and training have taught her many ways to keep residents engaged and calm. And, Mamah enjoys these ministrations. "I like dancing, so I dance" with residents. "I enjoy talking with them, laughing with them. I tell them my life story.

"I get to know them and their families," she says.

Huntington's units help residents preserve their voice and stories  Residents Peter Caldwell, left foreground, and Joseph Scannell participate in a session with speech therapist Peter Rahanis, right,in the Huntington's care unit at ArchCare's Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center in New York City. Julie Minda/© CHA It is usual for people with Huntington's disease to progressively lose their ability to communicate, due to the condition's effect on the organs needed to speak and on the mental processing skills needed to engage in conversation. Most of the patients who enter the Huntington's specialty units at ArchCare are experiencing significant disability; and they will stay at the facilities until their deaths. Several patients have lived a decade or more in one of the units. To help residents preserve their stories while they are still able to speak, caregivers create three-ring binders for each resident, with photos of the resident and their family members and other visuals. The binders also include typed descriptions of the person's background, including some of their favorite activities. Speech therapists at the unit at Terence Cardinal Cooke Health Care Center in Manhattan are supplementing the binders with computer-based photo and sound albums. Adjunct speech therapist Peter Rahanis of New York University explains that therapists download photos of the residents and their loved ones and then create links to audio clips of the residents describing each photo. This way, if the residents' verbal abilities decline, they can use the touchscreen to click on each photo and trigger their own voice describing why the photo is important to them. Eye-gaze technology is used for residents whose chorea prevents them from touching the screen. Resident Joseph Scannell has both a binder and computer-based "storybook." They feature his wife Merrill, his 21-year-old daughter, his 16-year-old son and information about Scannell's work as the assistant district attorney of Nassau County, N.Y. Scannell says when his children and wife come to visit, it's fun to look at the e-storybook together. He especially likes sharing the section where he talks about his favorite artist, Bruce Springsteen. Scannell put 10 of his favorite Springsteen songs in the book. — JULIE MINDA |

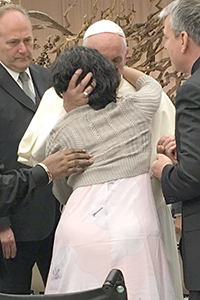

Pope Francis raises awareness of Huntington's  In May, Pope Francis held a special audience at the Vatican to increase public awareness of the plight of people with Huntington's disease. He is the first pope to do so. Among the many people with Huntington's disease from around the world taking part in the event was 24-year-old Bridgette Nathan, a resident of ArchCare at Ferncliff Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center in Rhinebeck, N.Y. Nathan, seen here hugging the pope, says of that moment, "I felt like a million bucks; I felt very connected to the pope." Traveling with a small contingent of ArchCare staff and supporters, Nathan also toured Rome during the trip. Originally from Jamaica, Nathan had lost her mother, brother and other family members to Huntington's disease before moving to New York at age 18. She was diagnosed with the condition that year. She moved to Ferncliff in June 2016. With no family in New York, and few family members left in Jamaica, Nathan says the staff at Ferncliff "are like my family now. It's a very loving place." — JULIE MINDA |

Nursing homes, psychiatric units not always ideal for people with Huntington's Because of the significant training and staffing demands needed to operate a specialized Huntington's disease unit, few nursing homes and psychiatric units have chosen to specialize in that type of care. That is according to Alicia O'Keefe, program coordinator for the Center for Neurodegenerative Care at Ferncliff, which is a unit at ArchCare at Ferncliff Nursing Home and Rehabilitation Center in Rhinebeck, N.Y. O'Keefe says that while the symptoms of other neurodegenerative diseases and other conditions common in nursing home residents may be similar to those of people with Huntington's disease, neither nursing home nor psychiatric facility placement may be ideal for a person with Huntington's disease. According to the Huntington's Disease Society of America, many people familiar with Huntington's disease say the multiple debilitating symptoms it causes are akin to having amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease simultaneously. All of these are progressive neurodegenerative conditions. ALS affects people's ability to control their movements; Parkinson's commonly causes tremors, gait and balance problems; and Alzheimer's negatively affects memory, thinking and behavior. People in the late stage of Huntington's disease may have that whole array of symptoms and so require assistance to perform any function of daily living. Total care necessitates more staffing per resident than is typical in psychiatric units and nursing homes, says O'Keefe. Too, Huntington's disease tends to worsen relatively early in people's lives, when they are in the prime of life. For younger people with the condition, a specialized facility may be preferable to a nursing home where all other residents are frail elders, O'Keefe says. O'Keefe says long-term psychiatric facility placement also is not usually ideal for people with Huntington's disease. While people with the condition may be placed in a psychiatric facility if they exhibit aggressive behaviors, most should not remain in such a facility for the long term. That is because staff in such facilities often focus on the psychiatric aspects of patients's conditions, and not on the full medical picture, says O'Keefe. Staff may not have a full understanding of chorea, or uncontrolled tremors, and some cognitive aspects of Huntington's disease. And psychiatric facility staff may not understand the importance of limiting the use of psychotropic medications, and to instead manage behaviors with other treatments, including exercise, therapeutic recreation and counseling, says O'Keefe. Staff in Huntington's-specific units are familiar with these approaches, she says. — JULIE MINDA |