By LISA EISENHAUER

While he says he respectfully disagrees with a bold call from some other prominent physicians in end-of-life care to do away with living wills and advance care planning forms — a plea that has been met with pushback — Dr. Ira Byock concurs that the way the process is widely practiced is ineffective.

Byock

"I think the controversy is misplaced and I suspect that if the people debating this were in the same room we'd probably come to substantial if not total agreement," says Byock, a leading palliative care physician and founder and senior vice president for strategic innovation of the Institute for Human Caring at Providence St. Joseph Health.

Dr. Colin Scibetta and Chaplain Stephanie Ryu visit the bedside of Josephine Courtney at Providence Little Company of Mary Medical Center in Torrance, California. The conversation included discussion of the goals of Courtney's care and aspects of her advance directive. The visit took place shortly before her death.

Providence Institute for Human Caring

James Robinson, advance care planning coordinator for the multispecialty medical group CHRISTUS Trinity Clinic that serves 200 locations across Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas, has a similar take on the viewpoint piece titled "What's Wrong with Advance Care Planning" that was published by JAMA Network in October.

He is not in favor of ending the practice but agrees improvements could be made. "I think we need to just refine what we're doing and expand what we're doing," Robinson says.

Authors cite lack of validity

The JAMA article doesn't hedge in its indictment of advance care planning that consists of completion of a form saying what treatments are wanted or not wanted far into the future, referred to in the piece as ACP. The article states plainly: "ACP does not improve end-of-life care, nor does its documentation serve as a reliable and valid quality indicator of an end-of-life discussion."

Morrison

Dr. R. Sean Morrison, professor and chair of the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, is the lead author of the viewpoint. He says the argument it presents is based on findings from dozens of studies of advance care planning that stretch back 25 years.

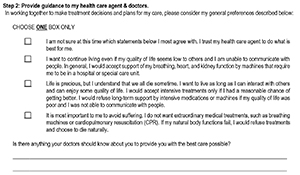

The two revised and simplified advance directives offered to patients at Providence St. Joseph Health facilities include the options shown here for patients to choose from to guide their health care surrogates and care providers on their care preferences.

"We haven't been able to show that ACP is an effective process of ensuring that people receive goal-concordant care at the end of life," Morrison says.

He considers the call he and his co-authors have issued to end advance care planning to be the only logical response to empirical evidence that the practice is not working. He compares it, for example, to how the medical community changed course on the use of estrogen supplements when research showed they were not beneficial and potentially harmful to postmenopausal women.

"And as a scientist, I have to look at the data, no matter how hard that is, and the data on this are crystal clear," Morrison says.

As to the timing of the opinion piece, he says one of the driving factors was what he has witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Too often, he says, he has seen overwhelmed and exhausted clinicians relying on living wills and other advance directives for guidance on patient care, rather than having meaningful, in-the-moment discussions with patients or their families about potential treatments and outcomes.

Shortcut for some clinicians

Dr. Diane Meier, one of Morrison's co-authors and a colleague, says that the use of advance directives such as living wills as "shortcuts in place of thoughtful, considered conversations with patients about their current situations" didn't start with the pandemic. Meier is founder and director emerita of the Center to Advance Palliative Care that is part of the Icahn School of Medicine.

She says advance care planning grew out of a movement to give patients who can no longer speak for themselves a say in their own care rather than allowing physicians to have sole discretion in treatment decisions. But that laudable and successful movement, she says, too often has given way to having patients fill out documents that, when a patient needs care and can't speak for himself or herself, are ignored or used as a blanket statement for care preferences.

"The best example is the overinterpretation of the do-not-resuscitate order to don't do anything," Meier says. "And that happens all the time. The public is perhaps not aware of this phenomenon, but clinicians working in the system know how do-not-resuscitate orders are often interpreted as a surrogate for comfort measures only."

She says she has had a "long-term increasing level of disquiet" about advance care planning as it has come to be practiced. She worries, for example, that Medicare, by giving care providers financial incentives to encourage patients to file advance directives is essentially rewarding those providers for "completing a form and checking a box." "There is no measurement of the quality of the conversation, of whether the clinician billing for advance care planning has ever been trained in how to initiate these conversations (most of us have had no training), and of whether the patient or surrogate understand what they are signing," she says.

Wrong incentives

What in her view instead should be incentivized is ongoing conversations about care preferences as well as continuity of care for patients so that they can develop trust-based relationships with their clinicians. In addition, she says, clinicians should be trained on communication skills so they are proficient at talking with patients and understanding patients' preferences.

"We don't incentivize continuity of relationships or demonstrating competencies in communication skills, but we could," she says.

In the opinion piece, Meier, Morrison and their co-author, Dr. Ronald M. Arnold, a specialist in palliative care and medical ethics at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, argue that "treatment choices near the end of life are not simple, consistent, logical, linear, or predictable but are complex, uncertain, emotionally laden, and fluid. Patients' preferences are rarely static and are influenced by age, physical and cognitive function, culture, family preferences, clinician advice, financial resources, and perceived caregiver burden." It is no surprise then, say the authors, that the gap between hypothetical scenarios set out in advance care plans and a patient's circumstances and care options at the end of life can be yawning.

A group of Providence St. Joseph Health workers in California fill out advance directives for themselves. In recent years, the system has begun offering patients simplified versions of a trusted decision-maker declaration and an advance care directive. The system's Institute for Human Caring has developed training curricula for clinicians on how to have more meaningful conversations with patients about serious illnesses.

Meier's advice to patients is to do two things: name someone they trust to represent them if they are no longer able to make their own medical decisions, as often happens during serious illness, and discuss with their proxy what they would want if they become permanently unable to recognize and interact with loved ones.

Some people say they would want care focused on their comfort if they were in a vegetative state, while others opt for all possible life-prolonging treatment, regardless of the quality of that life, she says.

"I present this question to my patients and ask 'Which kind of person are you?' so that I do not bias their choice," Meier says. "Full stop. That's it."

Praise and criticism

Meier and Morrison say, as expected, they have gotten praise as well as criticism for their viewpoint. The praise has included gratitude that they were bold enough to start a dialogue; the criticism has included that they haven't presented an easy alternative means for patients and families to make their wishes known to caregivers.

While they welcome the discussion of the merits of advance care planning, Byock and Robinson aren't endorsing an immediate end to the practice. Their systems are committed to counseling patients on advance care planning and, in fact, have recently acted to improve how that service is offered.

Byock takes issue with the argument made in the JAMA viewpoint in part because he finds it unclear what metrics the authors are using as the basis for their conclusion that advance care planning has failed to achieve the desired ends. "I don't think the field has ever decided what the measure of goal concordance would be," he says.

Drs. Diane Meier and R. Sean Morrison talk in a hallway of the palliative care unit at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Both are palliative care specialists and two of the three authors of a recent opinion piece in JAMA Network that urged a rethinking of advance care planning.

His own research and observations have shown that many patients and families are greatly relieved at having a trusted surrogate named and preferences for end-of-life care documented. He says he takes comfort in knowing that his own directive is in place.

"There's an old saying in medicine: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence," Byock says. "The fact that our measures aren't good enough to detect diminished stress at the time of decision-making or my own current feelings of having more confidence that I'm taking care of my family, that doesn't invalidate the benefit."

Premature conclusion

In his previous work as a hospital chaplain, Robinson says he too saw how advance care planning can lift the heavy burden of decision-making on families at the bedside of a gravely ill or dying patient. "If those conversations have already happened, that real concern is often alleviated."

In his view, the finality of the argument against advance care planning made by Morrison, Meier and Arnold is premature. He notes that the advance planning directive is still gaining a foothold in health care.

Robinson moved from chaplain to the newly created position of advance care planning coordinator just a couple of years ago, when CHRISTUS Health decided to offer the service to patients who come to its clinics for care. He said it was a need identified in San Antonio, a community in which many people don't have primary care doctors and aren't aware of how they can make their health care preferences known.

"The CHRISTUS program came out of the system's mission integration department," he says. "It didn't develop from a clinical standpoint or from operations or anywhere else. It came from mission, which means to me that we're doing it because it's something that we should be doing."

Systems simplify, innovate advance directive process

Advance care planning came into being in medical care in the middle of the last century. California in 1976 became the first state to pass a statute for a living will, a legal document that lets patients make their care preferences known and protects doctors if they follow those wishes in good faith.

Nationally, the practice of including patients' wishes in care delivery was codified in the Patient Self Determination Act of 1990. That federal statute directs care providers to "periodically inquire as to whether a patient executed an advanced directive and document the patient's wishes regarding their medical care."

Policymakers, health care systems and care providers have used various strategies to put the practice into place, including establishing protocols for discussions and drafting state-specific advance directive forms. It's only been since 2016 that Medicare Part B has reimbursed for advance care planning services. Some insurers do, too.

Shortcomings

Even with its relatively short history, Dr. Ira Byock says he and others who specialize in end-of-life care long have been aware of the shortcomings of advance care planning as practiced. Byock is a palliative care physician and founder and chief medical officer of the Institute for Human Caring at Providence St. Joseph Health.

One of the main flaws in the process is that often the documents that patients are asked to complete are both too complex and too generic, Byock says. Some of the directives ask patients to state whether they would want specific treatments at any time, offering them no opportunity to clarify under what circumstances they might be willing to undergo procedures such as dialysis or cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

"The large majority of people get to the part of the form with the menu of services and say 'Gee I don't know. I have to think about this. I better go home and talk to my family,'" Byock says. "And they take the form with them and you never see it again."

Shorter, simpler forms

Providence St. Joseph Health has moved in recent years to simplify the process through the use of two short forms. One is a trusted decision-maker declaration, a brief directive that does not require notarization or the signatures of witnesses to be entered into a patient's medical records and considered valid by the system.

In the declaration, patients name a health care agent who they authorize to speak on their behalf if they lose decision-making capacity. Patients also check one of four boxes to provide guidance on their care preferences.

The first box, which Byock says is the one most commonly checked, says: "I am not sure at this time which statements below I most agree with. I trust my health care agent to do what is best for me."

The declaration is signed by the patient and a licensed independent medical practitioner, who vouches for the patient's "decisional capacity." "By formal Providence policy, in the absence of an advance directive, these stand as evidence of the patient's verbally expressed wishes," Byock says.

The process of explaining the declaration to a patient and getting it filled out can take just a few minutes. And it can be done remotely, as has happened often during the pandemic, when Byock and other clinicians with expertise in advance care counseling have helped patients fill out the forms via video connections.

The other recently created directive that Providence offers to patients is basically the same form as the trusted decision-maker directive except that it has to be notarized or have the signatures of two witnesses. That document, which the system calls the easy form advance directive, aligns with statutory requirements for advance directives and not just with the system's policies for a valid directive.

Byock says the revised and simplified directives are "far more covenantal than contractual." He maintains that covenants are based on trust whereas contracts provide legal protections in situations where there is mistrust.

In addition to the simplified documents, the Institute for Human Caring has developed advanced communication training curricula to teach providers how to have more meaningful serious-illness conversations. More than 4,000 providers at Providence have taken these courses.

Workplace approach

CHRISTUS Health also is being innovative in its approach to advance care planning. In January, the system began an incentive program to encourage its employees to fill out advance directives. Those who do so through the program, which includes watching a short video and uploading their signed documents, get points that can be cashed in for gifts.

James Robinson, advance care planning coordinator for the multispecialty medical group CHRISTUS Trinity Clinic, thinks his system's program is one that insurers and other employers easily could adopt. It could help address the challenge of reaching people in a community where many don't have primary care doctors and don't make regular visits to clinics, he says.

Robinson coordinated the employee program for CHRISTUS Health but his main job is to talk with patients at family medicine clinics in San Antonio about advance care planning. Most of the people he speaks with are elderly patients who are at the clinics for Medicare wellness visits, though his services are available to any patient.

He says he keeps the conversations broad. His goal is to educate patients about care directives and to encourage them to fill out the documents so that they identify a trusted surrogate and their preferences are known by their loved ones and by doctors.

Archbishop Garcia-Siller

In addition to its employee program and its outreach efforts in clinics, CHRISTUS has a section of its website devoted to advance care planning. The postings include an appeal from San Antonio Archbishop Gustavo Garcia-Siller for patients to have health directives on file with their care providers.

"I think what we've done at CHRISTUS is a good example of what can be done elsewhere, so we're very excited about that," Robinson says.

CHA's advance care planning tools are available at chausa.org/palliative/advance-care-planning. Byock and Dr. Daniela J. Lamas discuss the merits and new frameworks for advance care planning on the Institute for Human Caring's Hear Me Now Podcast, at HearMeNowPodcast.org. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care physician at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

— LISA EISENHAUER