High turnover, worker shortages and burnout are taking a toll on workplaces these days.

U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy lists workplace well-being among his priorities. "We can build workplaces that are engines of well-being, showing workers that they matter, that their work matters, and that they have the workplace resources and support

necessary to flourish," he writes on his website, hhs.gov/surgeon general.

To offer insight on what keeps workers dedicated and motivated, Catholic Health World reached out across Catholic health care systems to ask several longtime employees why they have stayed where they are.

Bonnie Goldsberry, 48 years at Benedictine Living Community — Dickinson, North Dakota

Bonnie Goldsberry, 64, has lived in Dickinson, a city of about 26,000, all her life. That means in her role as activity director at Benedictine Living Community — Dickinson she encounters familiar faces. She's worked with former teachers, her dentist,

even her mother, who now lives at the eldercare facility.

Goldsberry

Goldsberry"The majority of these people are lifelong residents that I have known all my life, that have built this community to what it is today," she said. "I am very driven to serve them because they have given so much to this community."

Goldsberry started at the facility in November 1975 as a certified nursing assistant, staying in that role for several years until becoming activity assistant and finally activity director. She fills in occasionally as a nursing assistant.

Simply being present for the residents is part of the job for everyone on staff in Goldsberry's view. "Everyone needs to be out there, because that's where you get the real joy," she said. "That's where you make the big difference. Being with them."

As activity director, Goldsberry arranges crafts and games for the residents, transports them from area to area, helps them select meals, and organizes activities with the outside community. For Halloween the facility welcomed 500 trick-or-treaters, the

first major community event since the pandemic.

Goldsberry finds it most difficult in her job to see residents in the middle stages of dementia who don't fully understand why they are at the facility. It is also difficult for her when residents die, since she has known many of them and their families

for so long. She tries to go to their funeral and memorial services, she said.

Goldsberry has advice for anyone who wants to work in a nursing facility: exercise compassion, which includes being careful with body language and words. These residents didn't aspire to live in a nursing home, she said.

"You need to provide a little bit of love in everybody's heart to make it better for them," she said. "And if you don't have that, then don't even start. But if you want to experience real joy, come to a nursing home because you'll get it. You'll get

tenfold back what you give."

Sally Muehlius, 50 years at SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital — Fond du Lac, Wisconsin

Sally Muehlius, a nurse with SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital Family Birth Suites, prepares Anna Martin and her newborn son, Luka, for their return home. Muehlius has been with SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital for 50 years.

Sally Muehlius, a nurse with SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital Family Birth Suites, prepares Anna Martin and her newborn son, Luka, for their return home. Muehlius has been with SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital for 50 years.Sally Muehlius can't guess how many babies she's helped usher into the world. The registered nurse first started working at SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital in 1973. After one month in a medical unit, a position opened up in obstetrics, where she had hoped

to work.

"I slipped in and never left," she said.

She's been lucky to have great, reliable co-workers and bosses over the years. "They're helpful, and not running the other way," Muehlius said.

There's always something new to learn, and Muehlius, 70, marvels at the changes she's seen over the years. Now, babies mostly stay with their mothers, and the nursery is smaller and mainly for sick babies. Computer charting that she said takes longer

has replaced paper charting. Mothers automatically get IVs, and pain medications have evolved from gas to cervical blocks to epidurals.

"When I first started here, if the couple wasn't married, the dad couldn't go in for the birth. You'd have dads crying," she said. That changed soon after she started, and all dads have been allowed to stay with the mothers since.

Muehlius gets to know families, learning about their lives, and she likes to joke around and have fun. She takes time to show inexperienced parents how to feed, swaddle, and hold their babies.

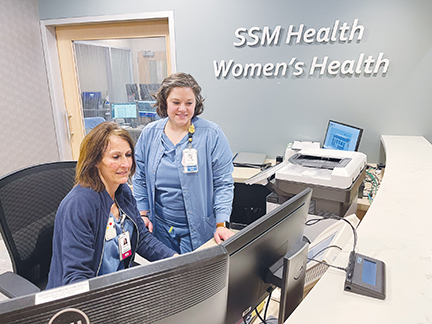

Sally Muehlius, at left, a longtime nurse at SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital, shares her knowledge and experience with her colleagues, including Josie Birschbach, a fellow nurse.

Sally Muehlius, at left, a longtime nurse at SSM Health St. Agnes Hospital, shares her knowledge and experience with her colleagues, including Josie Birschbach, a fellow nurse."It is a very good feeling to see that they are a little more comfortable," she said. "And as you see them through two days here, they're doing more things on their own."

She said the most rewarding part of her job is when a mother gives birth after a particularly long labor and delivery. "When the baby finally comes in, everything's going well, that is the best," she said.

Many mothers apologize to her after giving birth. They feel bad for not saying thank you or for taking so long. "To hear them apologize is like, oh, my gosh, that's crazy," she said. "I'm just so happy everyone is doing well."

Muehlius doesn't plan to retire soon. She works five shifts every two weeks, which still allows her to travel and have plenty of free time. "I get people who wonder, am I crazy?" she said. "It's a good feeling knowing I can (retire) if I want, but I like

it this way."

Pete Goeckner, 50 years at HSHS St. Anthony's Memorial Hospital in Effingham, Illinois

Pete Goeckner never knows what's in store for him when he comes to work each morning at HSHS St. Anthony's Memorial Hospital. He logs in and checks to see what work orders await: a leaky pipe, a malfunctioning hospital bed, an uncooperative ice machine.

Pete Goeckner

Pete GoecknerGoeckner, 67, faces each problem with a good attitude and usually has some dad jokes to share with whomever he encounters. "Some of them do laugh, and some of them roll their eyes," he said.

He started at the hospital part time when he was 16 years old, first working as a dishwasher and then as a cook's helper. Most of the time he's spent in maintenance.

"I was real green," said Goeckner with his tongue-in-cheek humor. "I've learned everything that I know now, which ain't much, on the job."

His official title is maintenance mechanic, and he works with a crew that handles work orders and does preventative maintenance, such as lubricating equipment. The crew plows the grounds and sidewalks when it snows. Members take turns staying on call

for emergencies.

Pete Goeckner, 67, a maintenance mechanic at HSHS St. Anthony's Memorial Hospital in Effingham, Illinois, started working there as a teenager.

Pete Goeckner, 67, a maintenance mechanic at HSHS St. Anthony's Memorial Hospital in Effingham, Illinois, started working there as a teenager."Pete is so consistent on every job he is given," said John Cordery, manager of plant operations at the hospital. "He reviews the work order and runs through the possible problem scenarios before heading out. He has a smile and greeting for everyone

he encounters on the way to the job location, whether a colleague, doctor, patient or visitor."

Since Goeckner grew up in the area and lives in nearby Teutopolis, Illinois, he often runs into people he knows at the hospital. He likes the people at his job and being in the company of other dedicated, long-term employees.

"I get along with maybe 99% of the people," he said. "You can't have 100."

He said he feels supported by an employer that always supplies what he needs to do his job.

He thinks he will retire soon, having recovered from recent shoulder surgery. But he's not sure. His son threw a retirement party for him a few years ago when he first planned to retire, but he put those plans on hold when his home's garage and its

contents burned in a fire.

Over the years, he's had opportunities to work elsewhere, he said. He can't see himself working in a factory or doing the same thing every day.

"I'm not a job jumper," he said. "If I like something, I stay with it, or tried to. Have I threatened to go to other places? I'm not saying I haven't. But was I serious? Probably not. I like what I do."

Nina Mayes, About 62 years at Bon Secours St. Francis Downtown — Greenville, South Carolina

Nina Mayes ticks off the specialties she makes for hungry staff, patients and visitors at Bon Secours St. Francis Downtown hospital: bacon, sausage and egg biscuits, lemon pound cake, banana pudding and a pineapple upside down cake with a glaze she

makes from the juice drained from the can.

"Then I spread that pineapple glaze on top, and I just give it a little bit of (yellow) food coloring to give it color, and it just stands out," she said.

Mayes, 80, has been with the hospital for about 62 years, minus a couple short breaks to work elsewhere. She comes to work every morning at 4:30 a.m., and usually leaves between 1 and 2 p.m. She said she's never called in sick and is never late for

work. She's even stayed overnight at the hospital during bad weather.

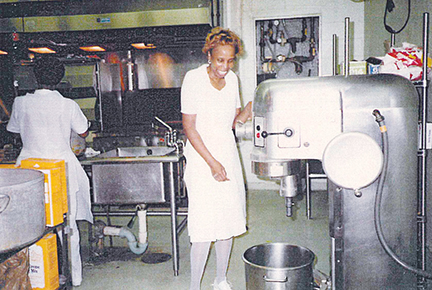

Nina Mayes, 80, has worked for decades at Bon Secours St. Francis Downtown in Greenville, South Carolina, most of it in food service as a baker. This photo is from her work area in the late 1980s, when bakers wore white uniforms.

Nina Mayes, 80, has worked for decades at Bon Secours St. Francis Downtown in Greenville, South Carolina, most of it in food service as a baker. This photo is from her work area in the late 1980s, when bakers wore white uniforms.Mayes started working at the hospital in the laundry department during summers in high school. After graduating in 1961, she started working in food service as a baker.

"I was almost like a human sponge," she said. "And I was just trying to soak up everything."

She trained on a brick-lined oven, and back then, everything was made from scratch, including fresh rolls she produced daily. Now, the rolls arrive as pre-made dough. She just has to poof and bake them. Still, she still makes about two-thirds of the

hospital's baked goods from scratch.

She loves trying new things in the kitchen and being creative.

"You know what? It keeps me motivated," she said. "Some of the things really aren't from scratch all the time, but you can tweak it. At least that's what the young people say."

She likes working for the hospital because she knows what her supervisors expect of her even as they give her a lot of autonomy.

"Over the years things change," she said. "I can't say I'm always happy with changes but figure you always can compromise. If you let things get negative, that will spoil everything."

She has no plans to retire soon and likes staying busy at the hospital. "Each and every day you only have that day, and I try to make the best of it," she said. "I'm so blessed."

Patty Putnam, 52 years at Open Arms Hospice, Bon Secours, Simpsonville, South Carolina

Patty Putnam is 77 years old and has no plans to retire soon. She loves seeing her friends and colleagues, and she loves helping patients and their families.

"I love just sitting and talking with people," she said.

Patty Putnam

Patty PutnamPutnam was hired as a staff pharmacist for St. Francis Downtown hospital in Greenville, South Carolina, in 1971. After about 10 years she became pharmacy director, and for the past 10 years has been the pharmacist for Open Arms Hospice in nearby Simpsonville,

also part of the Bon Secours system.

When she started, the hospital was run by the Franciscan Sisters of the Poor, who wore full habits.

"I've got to be honest, I'm an old south Georgia girl, and I had never seen a Catholic until I moved," she said. "These ladies knew their business, too. They ran the labs, they ran dietary, they ran pharmacy. That was such an eye-opener for me. That's

what got me started on my long journey on the right foot."

Working in a hospice presents its own emotional challenges.

After Putnam's first week, she returned to learn that 10 patients died over the weekend.

"I had a real hard time with that," she said. "But as I've worked with it over the years, and you see exactly what hospice really is and what it does for patients and the families, then you see it as a very positive thing. You're giving them something

that they're not going to get somewhere else. You're easing them out, so to speak."

Computerization has made Putnam's job easier. When she first started, she had to decipher handwriting, and she marvels that pharmacists didn't make more mistakes. "The world has improved patient care so much," she said. "And I think that's the way

we're able to help our patients — we're able to give it the best that we can."

The hospice has a large contingent of volunteers, who do things like delivering Thanksgiving dinners to families who have a member receiving hospice care.

"You can only do so much for a dying patient," she said. "You want them to be comfortable and you want to do the best that you can for them. But a lot of times the ones that are in need of support are the families."

Putnam said her employer is more focused on caring for individuals, including its own workers, than on profits. "We have to take care of our employees if we're going to take care of the patient," she said.