By LISA EISENHAUER

Before the start of each session of "Ethics on the Big Screen," Leslie Kuhnel wonders if participants will be searching for tissues before the evening is over.

Kuhnel

KuhnelKuhnel, vice president — ethics and theology for CHI Health, the Midwest Division of CommonSpirit Health, has seen the tears flow as program participants watch emotionally charged films and hear panel discussions on sensitive topics such as race-based

disparities in health care outcomes, living with mental illness, losing a loved one to dementia and facing the experience of homelessness.

The Ethics on the Big Screen education series has been hosted by the CHI Health Ethics Center in Omaha, Nebraska, for almost 20 years. Each session offers health care professionals the opportunity to explore the lived experiences of a particular patient population through a format

of film, didactic learning, small-group discussion and expert panel presentations — often including a first-person perspective from a patient or family members. Participants can earn continuing education credits and attend sessions in person

or virtually over Zoom.

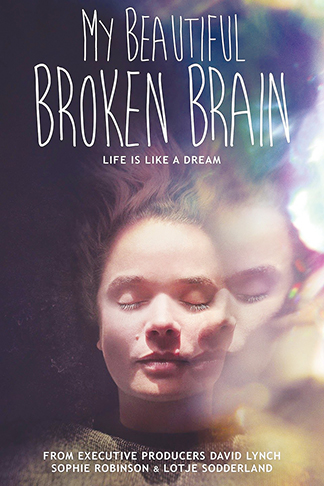

The documentary My Beautiful Broken Brain, about a woman's recovery from a stroke she suffered at 34, was the focus of discussion during the 'Ethics on the Big Screen' session in May.

The documentary My Beautiful Broken Brain, about a woman's recovery from a stroke she suffered at 34, was the focus of discussion during the 'Ethics on the Big Screen' session in May.The program's reach had been primarily local with a small regional following throughout the Midwest Division. But thanks to technology developments resulting from the COVID-19 response and a new partnership with a local Omaha arts organization, that has

changed.

Ethics on the Big Screen used the arts organization's theater for its spring event, during which the documentary My Beautiful Broken Brain was

shown and discussed. The session was live-streamed for the virtual audience. With the technological advancements, Kuhnel says, "We can offer a high-quality learning experience no matter where our colleagues are located."

With expanded promotion throughout CommonSpirit, the spring installment drew almost 130 participants from across the health system's 24-state footprint.

The program uses documentaries to help health care workers "recognize how social stigma and our own biases impact patient care, and how can we be better prepared to care for our patients with compassion and respect for their unique stories and experiences,"

Kuhnel says.

Each three-hour session starts with Kuhnel introducing the ethics topic. Following the film screening, attendees break into small groups for in-person or virtual chats about the topic. After that, a panel of health care professionals and people with related

personal experiences takes the stage to delve more deeply into the topic. Recent sessions have included medical students and other learners from CHI Health's academic partners, presenting basic information on the topic area of that session.

My Beautiful Broken Brain, the documentary shown in May, explores the struggles of a woman who has to relearn to speak, read and write after suffering a stroke at the age of 34. Kuhnel says the discussion that followed focused on "autonomy, personhood

and decision-making challenges" for patients recovering from a life-changing acquired brain injury such as a stroke. The panel included a mother who works as a care manager in the rehab medicine setting and who shared her family's story following

her son's brain injury.

The documentary Aftershock, which looks at how racial and gender bias affect maternal health care, was the topic of discussion earlier this year.

The documentary Aftershock, which looks at how racial and gender bias affect maternal health care, was the topic of discussion earlier this year.Aftershock, a documentary about how racial and gender bias factor into poor maternal health outcomes and high rates of maternal death among Black women, screened

at the January session. Doctors and midwives participating in the panel discussion talked about how to address racial inequities in maternal health care including by improving access to prenatal care for members of high-risk groups and by making

conscious efforts to counteract the impact of systemic racism and unconscious bias within this population in particular.

Also on the panel was Lynnette Zepeda, who shared her own story about the communication gaps that she experienced as a Black woman and how the initial treatment she got for an ectopic pregnancy made her feel like "a slab of meat on a tray."

Said Zepeda: "No one would tell me what was going on. They were getting ready to do surgery on me (and) I didn't know what they were going to do and I don't know what the outcome would have been."

But just before the procedure was to start, the lead physician came into the room and explained to Zepeda what was happening and why. The same doctor was at her bedside when she awoke after the procedure. The doctor, she said, "made me feel like

a human being and heard me."

Kuhnel says first-person stories such as Zepeda's are a powerful part of the participation experience at Ethics on the Big Screen sessions.

Kuhnel generally uses documentaries rather than feature films to anchor the discussion topics. "With more and more powerful stories being told through documentary films, we have the opportunity to dive deeply into a wide variety of ethics questions

in health care," she says.