Building infrastructure and transforming the care model to address disparities could take a decade

By LISA EISENHAUER The presidents of four competing hospitals on the south side of Chicago that together are operating in the red by about $76 million a year have agreed to combine their hospitals' assets and start a new system.

They said that system will expand access to preventive care and quality services, reduce drastic health inequities and provide economic development, jobs and training programs in the region.

Schneider

"We really think we've envisioned something here that is pretty bold and is transformational and should help to get our residents the level of care and the kinds of care that they deserve," said Carol Schneider, president and chief executive of Mercy Hospital & Medical Center, part of Trinity Health.

The nonbinding agreement signed in January by Schneider and the presidents of Advocate Trinity Hospital, part of Advocate Health Care; South Shore Hospital; and St. Bernard Hospital & Health Care Center calls for building several community health centers and at least one new, state-of-the-art inpatient acute care hospital to replace the four aging hospitals. Mercy Hospital and St. Bernard Hospital are Catholic.

Holland

Charles Holland, president and chief executive of St. Bernard Hospital, said that "individually the path forward was not sustainable" for the hospitals.

A new system

Schneider said the new system will operate on its own. "It will be a new company and it will not be associated with the legacy organizations," she said.

The new system will have an independent board of directors including a voting member from each of the legacy hospitals. According to a press statement, after a definitive agreement is executed, a benchmark expected by midyear, a chief executive and leadership team will be named and "each provider will contribute or transfer existing hospital assets to and help capitalize the new system."

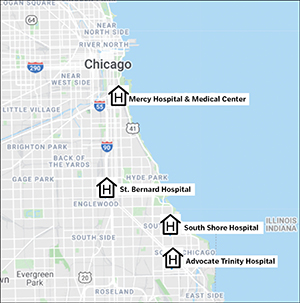

The four hospitals proposing a merger are in neighborhoods on the south side of Chicago. All of them are operating in the red.

The estimated capital investment to create the new system and network of facilities is $1.1 billion. In addition to funding from the hospitals, the plan foresees funding from state and federal sources and private donations.

"We started talking in September, so it's been pretty quick, but we all have very aligned goals and missions and kind of the same urgency to do what is best," Schneider said.

Holland said combining the hospitals' resources is a way to address "astounding" health disparities in the section of Chicago they serve. He and Schneider pointed to statistics that show, for example, that the overall life expectancy for residents of some south side neighborhoods is as much as 30 years less than for residents of other parts of Chicago.

Both executives stressed that the merger is a voluntary move by all four hospitals. "This is not being forced," Holland said.

He added: "Our commitment as the four presidents who've come together to put together this vision is that no facility that's currently operating would close until a new community health center is built and open and serving patients. Nothing would close until something new is built."

Together, the hospitals have 973 licensed beds. Mercy Hospital has the most, with 402 licensed beds. No decisions have been made yet on how many beds the hospital or hospitals in the new system will have.

All of the hospitals are losing money principally because they are not being adequately reimbursed by public insurers, Holland said. "We're safety net hospitals and the majority of our patients have Medicaid as a source of payment and in Illinois Medicaid doesn't cover the cost of care," he said.

Shifting to outpatient care

Schneider said the plan for the new south side system to open community health centers is in line with a state mandate to assist hospitals in "transforming their services and care models to better align with the needs of the communities they serve." The mandate includes looking at whether more services in a community should be shifted from inpatient to outpatient sites. "We're really looking at some behavioral changes (among patients) and offering access to care at the most appropriate level in an easy access way, instead of using emergency departments," Schneider said.

Community members and other stakeholders in the new system can share their thoughts on the plans at an upcoming series of community forums. The meetings "will help shape future hospital services, and the expansion of urgent care, ambulatory surgery, infusion therapy and behavioral health services at new community health centers, as well as specialty care, imaging and diagnostic services," according to southsidetransformation.org, a website with information on the merger. The website also says the merger is expected "to take the better part of a decade."

Holland said the new system will be nonprofit and non-Catholic. He said he and other executives who are working on the planned merger have had conversations with the Archdiocese of Chicago and "they're supportive of this effort to address disparities in health care and to really look community-wide at the need for a health care system on the south side of Chicago."

The executives are unaware of a similar merger anywhere else. "I'm under the impression that this is a very unique model in the nation, where four hospitals come together and contribute their assets, their property and say let's create something new here," Holland said.