By RENEE STOVSKY

It's common knowledge that human trafficking is a global issue that encompasses sex trafficking and labor trafficking, both of which are illegal. But considerably less attention is paid to ways in which skilled and unskilled workers can be exploited.

"There are nannies forced to work seven days a week, with responsibility for child care 24 hours a day," says Sr. Rosemary Donley, SC, a professor of nursing at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. "There are nurses from the Philippines and India who may be working under contracts that limit their freedom of travel and have landed them in hospitals where nobody would want to work — places where incredible staffing difficulties make the work untenable for all staff. The nurses can't exit their contracts without paying penalties to the staffing company equivalent to several years' salary. We should be concerned about these workers as well."

Sr. Donley

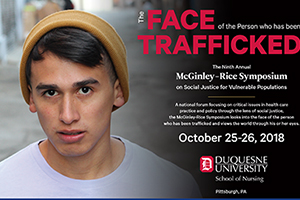

Sr. Donley, who holds the Jacques Laval Chair for Social Justice in Duquesne University's School of Nursing, organized the upcoming conference "The Face of the Person Who Has Been Trafficked," the ninth annual McGinley-Rice Symposium on Social Justice for Vulnerable Populations. It will be held Oct. 25-26 at Duquesne University. (Registration deadline for the conference is Oct. 19; information can be found at duq.edu/academics/schools/nursing/mcginley-rice-symposium)

In addition to sex trafficking and labor trafficking in industries like agriculture and fishing, conference speakers will touch on ways in which restrictions on workers can impinge upon their dignity as workers and their personal freedoms.

Vulnerability and naivete

One of the scheduled panelists is Mukul Bakhshi, an attorney who directs the Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices, a division of Philadelphia-based CGFNS International. CGFNS describes itself as an "immigration neutral nonprofit" that assesses and validates the academic and professional credentials of foreign-educated health care professionals seeking to work outside their country of origin. Bakhshi says that exploitation of foreign nurses through questionable contract practices has elements that are reminiscent of indentured servitude.

"Though most foreign nurses have positive experiences working in the U.S., others are treated like indentured servants, subjected to bait-and-switch tactics in terms of assignments and threatened with high breach fees if they try to leave a contract," says Bakhshi.

He says problems with unethical recruitment of foreign nurses have grown in the past decade as the labor market has tightened. Moreover, fewer hospitals are directly employing these nurses. Instead, most foreign-educated nurses seeking employment in the U.S. now depend on third-party recruiters in their home countries to link them with staffing agencies.

"In the staffing firm model, nurses are employed by the staffing firm and work under contract to health facilities. This can lead to problematic recruiting," he says. He calls on hospitals to be proactive in heading off potential problems by using recruiters who are certified by the Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices. (See sidebar.)

Sr. Donley adds that while there are a small number of bad actors, most nurse staffing companies that recruit foreign-educated nurses to the U.S. operate ethically. However, she says nurses may enter contracts without a full understanding of the implications. "Should they take the contract to a lawyer before they sign it? Yes." But that is not common practice by workers in emerging economies, she says.

Up-front investment

The staffing agencies typically pay for up-front costs including fees related to obtaining a special work visa, relocation to the U.S., preparation for credentialing tests and lodging during that training and orientation. In exchange, the nurse agrees to work under contract to the agency — usually for three years — and may contractually waive a right to a jury trial should a legal dispute arise. After three years of employment with the staffing agency, the nurse is released from the contract and is free to take other jobs, if visa status allows.

Bakhshi says CGFNS' VisaScreen is the only nurse credentialing service in the U.S. that is approved by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security in applications for occupational visas. The great majority of applicants for the credential validating service are female nurses, most of whom come from the Philippines, followed by India and China.

The poster for an upcoming seminar on human trafficking, which aims to educate nurses on the issue.

In 2017 CGFNS issued more than 5,000 VisaScreen certificates for nurses. That's down from a high of 17,000 in 2004, during a peak period in foreign nurses immigrating to the U.S. Historically, the number of foreign nurses sponsored by employers to enter the U.S has been expanded and contracted to address shortages and surpluses in the labor market. With the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projecting that by 2024 there could be a shortage of a million registered nurses in the U.S., experts expect health care providers to attempt to increase their reliance on foreign-educated nurses. Bakhshi says that as recruitment rises, so do the risks that workers will be vulnerable to unscrupulous recruitment tactics or enter contractual commitments without a full understanding of the terms.

"Foreign nurses are in very vulnerable positions. They can be placed in substandard housing during training and have very little control over job placement, titles and staffing ratios. They can face harassment and discrimination at work and are less likely to seek redress," for fear their immigration status would be put at risk, says Bakhshi.

Sr. Donley adds that foreign nurses typically send money back home, and families that supported their nursing school education planned for — and now rely on — the income. This obligation makes foreign nurses more vulnerable to being exploited. "You could say they got themselves into it; they signed the contract. Sure they did, but they had no idea what they were getting themselves into," she says.

Patricia Pittman, a professor at the Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, led a study published in 2014 on the perceptions of employment-based discrimination among foreign-educated nurses. The survey showed foreign-born nurses that had been recruited to the U.S. by health care staffing agencies and nurses who emigrated from developing countries "tend to be especially vulnerable to low wages, placement in less desirable jobs or undesirable shifts."

Foreign-educated nurses who renege on their contracts with staffing agencies can face civil breach of contract suits. Staffing firms may try to recover not only their up-front outlay but also their lost revenues from wages that would have been earned over the life of the contract. Companies have at times demanded six-figure settlements.

Clearer communication

One such case settled in August in South Florida involved a dispute between a Filipino nurse working in the U.S. and Sunrise, Fla.-based MedPro Healthcare Staffing. The settlement set out new protections for foreign-educated nurses who sign employment contracts with MedPro.

The defendant, Eden Selispara, was sued by MedPro for $156,000 in a breach of contract action. She was represented by Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer advocacy organization, in a countersuit that claimed MedPro had failed to find her employment after she completed training in the U.S. Selispara says that when she complained about the "untenability of indefinite unemployment without pay and confinement in South Florida" where MedPro provides professional training to foreign nurses, MedPro employees "threatened to make a baseless report of (immigration) fraud to U.S. immigration officials."

According to a press release on the settlement from Public Citizen, MedPro agreed to modify its practices "so that nurses and other health care professionals better understand the terms of any contracts they are presented with, that nurses are paid for time spent in mandatory training and orientation and that lawsuits or reporting to immigration are not used as threats." As part of the settlement, MedPro, while admitting no wrongdoing, agreed to cap the amount it demands in breach of contract suits at $40,000 and to offer workers who exit the contracts a payment plan rather than requiring immediate restitution.

Liz Tonkin, the president and chief executive of MedPro, said in a press release issued in conjunction with the settlement, "MedPro is always looking for ways to improve the experience for our employees and candidates so we can be the trusted leader in the recruitment and placement of foreign-educated health care professionals."

Research and resources A website developed by David Nolfi and Liz Waltman for the Gumberg Library at Duquesne University contains facts about human trafficking and testimonials from survivors. Find it at: http://guides.library.duq.edu/human_trafficking CHA's resources on preventing and interrupting human trafficking are published at chausa.org/human-trafficking/overview |

Heightened awareness can safeguard foreign-educated nurses in the workplace  Bakhshi What can health care facilities do to help combat inequitable treatment of foreign-educated nurses employed by staffing agencies? Mukul Bakhshi, an attorney who directs the Alliance for Ethical International Recruitment Practices, a division of CGFNS International, has these suggestions: - Be certain to work with reputable, certified recruiters and health care staffing agencies that commit to ethical practices. CGFNS lists recruiters and staffing agencies it has certified as being compliant with its code for ethical recruitment of foreign professionals. The list is published at cgfnsalliance.org/certification_process. Click on "new certified recruiters."

- Administrators also can ask to review recruiters' operating practices and employment contracts and inquire if foreign nurses can negotiate on their own behalf.

- Provide a direct channel from the foreign nurse to the human resources department at the hospital or health care facility where he/she is working. The goal here is to be an intermediary between the staffing firm and the nurse where appropriate. Encourage nurses to contact HR directly if or when they encounter problems.

- HR personnel should advise nurses on acceptable living conditions, commute times, staff ratios, shifts and so on. Let them know what their rights are so they will know when those rights are being violated.

- Hospitals can raise cultural consciousness by educating staff on unacceptable microaggressions and hidden prejudices. Much of the exploitation and discrimination foreign nurses encounter is done at the "micro level," according to Bakhshi. Nurse managers and direct supervisors should be alert to any bias against foreign nurses. Poor communication skills may hamper interactions with colleagues; educational experiences may differ; job assignments may be inappropriate or cultural practices may be different. Multicultural training can help people appreciate differences and lead to better work environments.

|