By KATHLEEN NELSON

Like many of his colleagues, Dr. Syd Hindley cares for a growing number of patients with advanced chronic illness. An emergency room physician at CHI Franciscan's St. Anthony Hospital in Gig Harbor, Washington, Hindley has no working relationship with these patients, who arrive suffering debilitating symptoms and a decreasing quality of life. Some have reached a point where curative treatments offer little to no chance for improvement; some have difficulty managing the symptoms of a serious chronic illness. In both cases, palliative care treatments could provide relief and support.

Hindley

Even so, broaching the topic of palliative care can lead to a critical and intimate conversation about prognosis and life goals, a conversation where respect and empathy are paramount.

"Too often, we have to make a deep connection on the spur of the moment and have a difficult conversation with very little background," he said. "It isn't easy to get from, 'Hey, I just met you and now I'm recommending that we can either do something that could make you feel worse or focus on easing your symptoms rather than seeking a cure.' They don't teach those skills in med school or residency."

Iregui

Hindley helped fill the gap in his training by attending CHI Franciscan's Palliative Care Academy, a two-day training program that blends the palliative skillset of supportive care and symptom management with ethics and communication.

Dr. Juan Iregui, a hospice and palliative care specialist at St. Joseph Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington, and a member of the CHI Franciscan system's ethics committee, leads sections of the training. "We tend to see ethics at 30,000 feet, as something theoretical, but it really belongs bedside," he said. "This training brings our ethics back to Earth."

The basics of difficult conversations

The journal Heart Failure Reviews reported in 2017 that there was just one palliative medicine specialist for every 1,200 people living with a serious or life-threatening illness — versus one cardiologist for every 71 people experiencing a heart attack. With so few specialists in palliative medicine, clinicians in other disciplines need a broader understanding of the scope and benefits of palliative medicine. Participants in the Palliative Care Academy learn simple and practical techniques to offer supportive care in the form of symptom and pain management as a complement to, or replacement for, curative treatments.

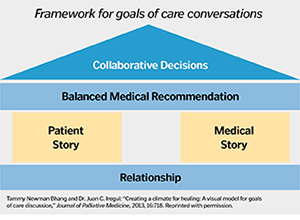

A simplified schematic of The House Model illustrates a patient-centered approach to conversations about palliative care and advanced care planning for end-stage disease.

They discuss ethics and the fundamentals of specific treatments, such as artificial nutrition, hydration and management of pain and breathlessness. The training supplements this clinical information with sessions on patient communication that deal with breaking bad news and matching medical treatments to the preferences of the patient and family.

"We're really not trying to teach people palliative care. We want to get in front of primary care doctors, nurses, social workers, really everyone on the team to improve basic communication skills," said Dr. Mimi Pattison, regional medical director for CHI Franciscan Hospice and Palliative Care and chief facilitator of the Palliative Care Academy. "It's so amazing how everyone can take these basic skills and apply them the next day."

Hindley signed up for the training after seeing the improvements in quality of life that palliative care provided to his grandparents at the ends of their lives. He also regularly treats patients in the ER with terminal, serious or chronic conditions and wanted to learn more about treatment options for managing symptoms and pain. He got so much more.

"Juan and Mimi give you this foundation for how to frame questions and approach the conversations and address these concerns," Hindley said.

Listen first

Iregui and Pattison base the communications training on what they call The House Model, built on a foundation of asking and listening, rather than telling: asking for permission to hold a conversation, listening to the patient's history and goals and asking for permission to make a balanced recommendation based on what is important to the patient and what the physician knows about his or her medical condition.

Participants cite this "ask before you tell" approach as the most transformative piece of the two-day training.

Dr. Mimi Pattison, regional medical director for CHI Franciscan Hospice and Palliative Care and chief facilitator of the Palliative Care Academy, leads a pre-COVID training session. She says the connection that many clinicians make between palliative care, hospice and dying keeps them from recommending palliative care to patients who could benefit.

"The interesting thing about the process is that it's very collaborative," Hindley said. "You ask a lot of questions, but there are also specific points where you ask for permission to offer a medical recommendation. So, you don't really leave the patients on their own. You collect the information then give them an informed recommendation based on what they tell you."

In addition to training as many clinicians as possible, Pattison hopes to move participants away from thinking of palliative care as giving up on a patient, or solely as hospice, which provides palliative care and emotional support to patients with end-stage terminal illness. She wants palliative treatments integrated into a care continuum.

Anytime, anywhere

"In the course, we talk about how palliative care is for anyone, anytime, anywhere, any diagnosis," she said. "Most people who need palliative care aren't dying. And people are shocked when they hear that because it's so linked to hospice. We really work to uncouple that connection between palliative care, hospice and dying."

Hindley noted that he uses the skills from the academy more than once a week, not just in conversations with terminal or gravely ill patients but in helping on less critical decisions of care.

"There's nowhere near enough discussion of palliative care," Hindley said. "Every patient in (intensive care) should have a palliative care consult to discuss goals of care and improve their comfort. It should be done for every patient with a cancer diagnosis, to talk about the process of care. It should be a standard part of a care plan."

The program has been offered once a month since 2015 and has trained more than 800 clinicians across disciplines: obstetricians, oncologists, hospitalists, psychiatrists, cardiothoracic surgeons. Most of the participants are employed by or affiliated with Catholic Health Initiatives facilities in the Pacific Northwest. Some program participants have come from other health systems and from the region's community health service providers. The training is so popular that sessions are booked a year in advance.

COVID-19: Challenge and opportunity

As with every aspect of health care, the outbreak of COVID-19 has presented challenges and opportunities for the academy. Sessions were capped at 13 participants before the pandemic and have been reduced to six because of the need to social distance. But working with CommonSpirit Health, CHI's parent ministry, Pattison and Dr. Christine Cofer of the Palliative Care Academy have developed a virtual version of the course that meets for three days in three-hour sessions. After finishing the first online session in July, they offered a second session in August. They plan to refine the presentation and are encouraged at the possibilities.

"I was surprised how effective it was," Iregui said after the July presentation. "A lot of the activities are the same. It can't totally replace the in-person sessions but may turn out to be more effective in delivering the training to a broader audience."

When care conversations matter most, listen first, talk later

The Palliative Care Academy teaches communication techniques based on The House Model, developed by Tammy Newman Bhang, the academy's former director, and Dr. Juan Iregui, palliative care specialist at St. Joseph Medical Center in Tacoma, Washington. The hallmark: Ask before telling. Following are the model's five elements and some of the guiding questions for physicians:

Foundation. After creating a quiet, safe space, ask for permission to begin the conversation through a question such as:

"We want to provide the best care possible from your perspective. Can we talk about that?"

Patient story. The key is to gather emotional and cognitive data by asking such questions as:

"Can you tell me, in your own words, what have you heard about your condition?"

"Where do you get your strength and support?"

"What is your body telling you?"

Medical story. Only after listening, ask to share medical information. Iregui and Bhang suggest delivering the news in a headline, for example:

"I'm worried that what we are hoping for may not happen," then letting the patient break the silence.

As a follow-up, "Given your medical situation, what is most important to you?"

Recommendation. After repeating their concerns and priorities, ask permission to offer a treatment that aligns with their goals, then ask:

"What do you think about this as a plan?"

Collaborative decision making. The goal is to ensure the quality of the collaboration, rather than judge the quality of the decision. Physicians should summarize and affirm the patient's decision and perhaps offer next steps, such as a time-limited trial of a treatment with a specific goal, then ask:

"To make sure I have done a good job communicating, can you share with me what we talked about?"