Students gather in a parking lot near St. Louis' Central Visual and Performing Arts High School after a shooting there last fall. The Archdiocese of St. Louis convened a firearms summit this summer focused on how to reverse the tide of gun violence.

Health care workers were among those who spoke out. Photo by David Carson/St. Louis Post-Dispatch via AP

SHREWSBURY, Mo. — After the shooting death of 9-year-old Evelyn Dieckhaus along with two other students and three adults at a school in Nashville, Tennessee, in March, members of her grandparents' parish more than 350 miles away in Washington, Missouri,

gathered to pray.

"People showed up in great numbers, not really knowing what to say," said Fr. Mike Boehm, then the pastor of the parish, St. Francis Borgia. "It was really a time for our church to be seen as a beacon of hope."

Fr. Boehm was among those who called for the Catholic Church to become a beacon of hope — and action — during a daylong summit to address gun violence convened by the Archdiocese of St. Louis. About 350 people gathered for the July 29 event,

called "Addressing Gun Violence: Promoting a Culture of Life."

The summit featured several speakers and panelists, including Fr. Boehm, who discussed the impact of gun violence. After a lunch break, participants met in workshops on topics such as ministering to survivors and advocating for sensible gun legislation.

"As a church committed to the value of life, we need to address these issues with our Christian Catholic perspective," St. Louis Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski told the crowd. He is the liaison between the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

and the CHA Board of Trustees.

Archbishop Rozanski noted that the bishops conference has spoken pointedly about gun violence, including sending a letter to Congress calling for action after the mass shooting at Uvalde, Texas, in 2022 that took the lives of 19 children and two teachers. "We cannot stand by without living our faith and addressing the issue of gun

violence," he said.

Garza

GarzaA widespread problem

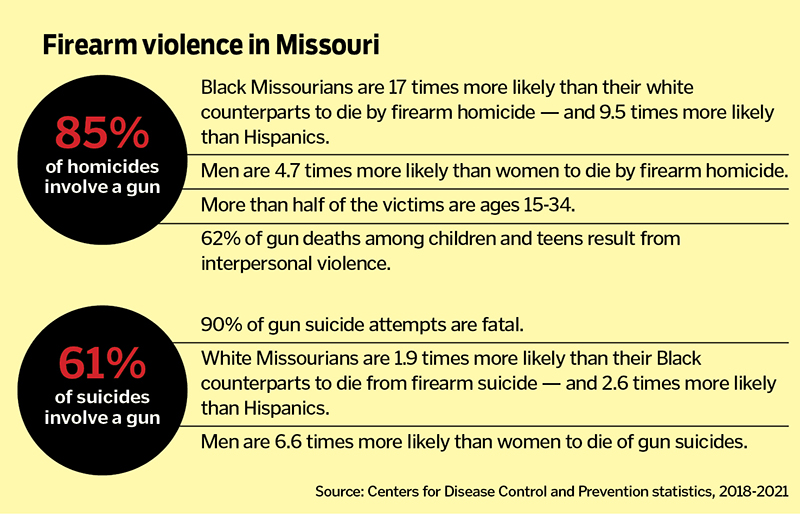

Dr. Alexander Garza, chief community health officer for SSM Health,

pointed out that in 2021 there were more than 48,000 firearm-related deaths in the United States, with 134 people dying each day. Over the past 10 years, the death rate due to firearms has increased by almost 40% nationwide, according to Garza, citing

data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The firearm death rate in Missouri is among the highest 10 in the nation, he said. In the counties that make up the St. Louis archdiocese, 57% of firearm deaths are homicides, compared to 44%

across Missouri, he said. The other gun deaths are suicides.

Most of the gun violence victims in Missouri — 85% — are male, with Black Missourians 17 times more likely than those who are white to die by firearm homicide, he said. Of people who take their own lives by gun, they are 1.9 times more likely

to be white than Black and 6.6 times more likely to be men than women, he said.

Garza hopes people see that the issues surrounding deaths and injuries from firearms are complex, he said. "They're not just a law enforcement problem," he noted. "They're not just a public health problem. It's all of our problem."

Kathy Gilbert and Kim Westerman, who have advocated for laws they say will decrease gun violence in Missouri, spoke about the current state – a "sad" state, they said – of its laws. Both the Giffords Center for Violence Intervention and Everytown

for Gun Safety give Missouri's laws a low rating. Both groups and several others have found a direct correlation between the strength of gun laws in Missouri and the number of gun deaths and injuries, and some of the state's gun laws have loosened

in recent years, Gilbert and Westerman pointed out.

Jessica Woolbright, the executive director of Saint Martha's, a shelter and drop-in center in St. Louis that helps women and children experiencing domestic violence, noted she is a daughter of a state trooper and grew up with guns in the house. In 2020,

the state of Missouri ranked sixth in the country for women murdered by men, she said. The state requires people who have full orders of protection against them to turn over their guns to a friend or family member, but that isn't enough to make women

feel safe, she said.

"So my hope for today is that all of us find ways to find common sense. Because here's the thing: right now, both literally and figuratively, all we're doing is putting Band-Aids on the problem," she said. "And until we are willing to step up and take

that next step to protect the most vulnerable around us, that is what we will continue to do."

A school shooting hits home

Tobias Winright is a professor of moral theology at St. Patrick's Pontifical University in Maynooth, Ireland. Before that, he served as an associate professor of theological ethics and health care ethics

at Saint Louis University, and before that, he was a police officer and correctional officer. When the family moved to Ireland, his daughter stayed in St. Louis with friends to finish her senior year at a St. Louis high school.

St. Louis Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski listens from among a crowd of about 350 people who attended the firearms summit led by the archdiocese at the Cardinal Rigali Center in Shrewsbury, Missouri. The archbishop and many other speakers called for the Catholic Church to take a lead role in finding ways to address gun violence. Photo by Valerie Schremp Hahn/@CHA

St. Louis Archbishop Mitchell T. Rozanski listens from among a crowd of about 350 people who attended the firearms summit led by the archdiocese at the Cardinal Rigali Center in Shrewsbury, Missouri. The archbishop and many other speakers called for the Catholic Church to take a lead role in finding ways to address gun violence. Photo by Valerie Schremp Hahn/@CHAHe recounted the day last October when he and his wife got a text from her saying her school was under lockdown because of gunfire. A former student was on a rampage, killing a teacher and a student.

"My daughter had to step over this student's body to escape," he said, showing a slide with a photo of 15-year-old Alexandria Bell. Central Visual and Performing Arts High School where the shooting took place shares a campus with the school Winright's

daughter attended, Collegiate School of Medicine and Bioscience.

The decision to move to Ireland was difficult, but the gun issue factored into it, Winright said. He pointed out that Ireland is a "very Catholic" country, with about 50 to 70 gun deaths a year.

At the summit, he reviewed the long history of nonviolence taught by the Catholic Church, which he said stresses that lethal force must be used in moderation. "Rights are always accompanied with responsibilities," he said.

Michael McGrath is a special agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. He lives near the St. Louis school where the shooting took place and responded immediately. As he looked for the shooter, he evacuated students. It was strange

to see both innocence and terror in their faces, he said.

"One tall, sweet kid, through a face full of tears, said 'Thank you. Thank you so much.' So we reassured him," McGrath said. "It was clear that this young man had spent an unacceptable amount of time wondering if that was his last day. And I mean that

absolutely in the most literal way you can think."

While his passion for justice is inextricably linked to his faith, McGrath said he and his colleagues in law enforcement see "unacceptable levels of human violence." He said they agree that their related stress and mental fatigue has been long lasting.

Empowering responders, survivors

Kyle Dooley, a former police officer, spoke about the five members of his family, including his father and grandfather, who died by suicide with a handgun. He now trains police officers on how to

respond to people experiencing a mental health crisis in his work with the National Alliance on Mental Illness St. Louis.

The group has trained more than 7,000 police officers in the St. Louis region.

"I have realized that I touch more lives today than I ever touched as a police officer arresting people and putting them into our criminal justice system," he said.

Atif Mahr shared that in the months following the fatal drive-by shooting of his 19-year-old daughter, Isis Mahr, he relied on the help and support of his parish family and his faith in God. Two men were charged in the shooting, but the primary witness

died. In July, less than two weeks before the summit, the charges were dropped.

Mahr's daughter wanted to be a nurse. After her death, he started a foundation in his daughter's name to mentor youth who would like to become nurses.

"To walk with the spirit of God teaches me to be a blessing to my community, to say, 'Hey, I need to forgive, move on, so I can continue to live in a godly manner,'" Mahr said. "And whatever God has planned, it will bring her justice."

Lori Beck, a trauma nurse specialist with St. Louis Children's Hospital, spoke about her 28 years of taking care of kids injured or killed by firearms. "It takes a toll," she said. "I remember faces. I remember their stories. I very clearly remember the

sounds of grieving families."

When she first started at the hospital, she and her colleagues took care of three to five firearm injuries a year. Now, it's more than two gunshot wounds a week, something they handle with the same frequency as simple surgeries like appendectomies.

A few years ago, Children's and St. Louis-based BJC HealthCare began giving away gun locks. They since have handed out about 30,000 in all. Preliminary data shows that the number of intentional firearm injuries seen since at Children's has remained about

the same, but unintentional injuries are down by half, she said.

Looking out at the crowd, she said: "This gives me so much hope. I do know I want to be part of the solution."