BY: ANN NEALE, PhD

Dr. Neale is senior research scholar, Center for Clinical Bioethics, Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, DC.

A Writer Suggests an Exercise that Readers Can use to probe Their Own Attitudes

How do beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors help or hinder health care justice? How, specifically, do the beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors of those of us who work in health care affect health care justice? In this article, I offer a practical exercise that can be used to probe such phenomena. I offer the exercise not just for private reflection — for, that is, an individual's examination of his or her conscience — but also for groups seeking to do what has been called "public conscience work."*

* John W. (Jack) Glaser, STD, senior vice president, theology and ethics, St. Joseph Health System, Orange, CA, coined the phrase "public conscience work" to refer to the effort required on the part of the general public in the transformation of U.S. health care.

Readers who undergo the exercise will, I think, discover that taking time to reflect individually can be a useful way to explore one's own ambivalence about U.S. health care. Clarifying basic value choices that lie at the heart of our struggle for a more just and sustainable health care system can shed light on the tradeoffs inevitably involved in policy change. Honest, open discernment concerning these issues promises to bring greater integrity to the struggle and greater leverage to the reform effort. Furthermore, group reflection — public conscience work — can reveal the extent of our common ground, build community, and empower us to take the collective action necessary to address the structural injustices in U.S. health care.

Rationale for This Exercise

Virtually everyone agrees that U.S. health care is at a crossroads. It faces many challenges — the most evident being unsustainable cost increases† and diminishing access.§ For decades, attempts at reform have been unsuccessful. As a nation, we have not been able to get behind a policy proposal that adequately addresses our health system's many failures. One reason our traditional approaches have not worked is that we have not brought to those efforts sufficient reflection concerning the deeper, values-level attitudes concerning reform. Instead, the reform movement has concentrated on promoting particular policy solutions.

†Current trends suggest that health care will comprise 35 percent of the nation's GDP by 2040.

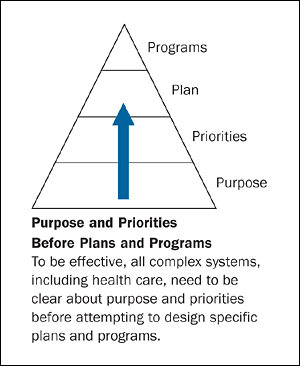

Ultimately, of course, we must agree on a delivery and financing system if we are to redress the situation. But first we must recognize that U.S. health care's fundamental challenge is moral and social in nature. Before we decide the technical issues related to changing the system, we need considerable individual and community soul-searching at the level of values and priorities. We need to come together as a community to reflect on:

- What is important to us about health care?

- How should a good community live together in respect to this issue?

- What limits, if any, should neighbors be willing to accept if we all are to receive the health care we need?

We need to address openly the fact that health care is but one social good among many and only one factor in achieving healthy communities. Tradeoffs are inevitable. Conscience work can help us to choose wisely.

In particular, I propose that those of us who are involved in Catholic health care examine our consciences from the perspective of cultural awareness and Catholic social teaching. Such introspection is important for two reasons. The first has to do with personal integrity.

Maintaining Personal Integrity

We tend to bring our values to bear on external realities. In the ministry's long history with health care reform, we have evaluated the current and possible health care systems in light of Catholic social teaching and recommended policy that better reflects that teaching. Our principle-driven advocacy presupposes ongoing introspection and corresponding efforts to ensure that we are personally and professionally aligned with the principles and values entailed in the policy positions the ministry supports. That is, our advocacy and lobbying have presumably emanated from personal convictions that manifest the principles according to which we judge and attempt to transform U.S. health care.

This is an important, but perhaps not altogether warranted, assumption. After all, we are part of a culture that glibly assures pollsters that "everyone should have access to health care regardless of ability to pay" — and then lives with a scandalously different reality belying the culture's values-laden protestations. An examination of our individual consciences will provide us an opportunity to compare our professed versus our actual beliefs and the way those beliefs influence our personal and professional lives.

Creating Social Change

The second reason for conscience work has to do with social change. Huge social change will be required to transform U.S. health care. That's because the current system is so deeply embedded in a multitude of stakeholders, including the 2,000-year-old medical profession and health care professionals in general; organizations delivering health care; the medical-industrial complex that supports and benefits from those organizations; and health care users, including ourselves.

Stakeholders will not let go of the status quo until a critical mass of people becomes convinced that there is a serious moral and social imperative to do so. Social change of this magnitude is not simply a matter of comprehensive new policy. To be effective, it must be accompanied by sustained individual and public conscience work that grounds a significant social movement comprising a critical mass of each of those stakeholders.

Multiple Lenses

The propositions suggested here can be viewed through a number of "lenses," including the social and medical cultures and Catholic social principles.

Social and Medical Cultures

We Americans live and work in a materialistic, individualistic culture whose values challenge health care's social and altruistic nature and whose policies can actually limit the good that health care professionals and organizations can accomplish.* Because human beings are inevitably influenced by the prevailing culture, I propose that, as we probe our behaviors and motives, we keep in mind some of our culture's prominent characteristics, including the following:

- We are reluctant to accept limits. Our society prizes progress, technology, and innovation. There is always more we might have and do.

- We have a strong allegiance to the market, uncritically accepting its claims of efficiency and its corollaries concerning individual freedom and choice. And concerning the market (where "more" is always a good thing), we believe that, in the end, market forces ultimately work to everyone's benefit.

- We attribute material wealth to individual effort, placing no social constraint on its accumulation or use.

- We are a society that accepts great discrepancies in regard to income and health security, and wealth and opportunity.

- Our expectations of modern medicine are virtually boundless — to cure all disease, to extend the life span — an "infinity model," as Daniel Callahan, PhD, has put it.

- We have a high-technology medical system oriented to the care and cure of individuals and focused on institutional care; health promotion and prevention and population-health receive much less attention.

- Health care costs are rising steadily, imposing increasing burdens on individuals, businesses, government, and health care providers. But those burdens are increasingly shifted away from business and government and onto individuals.

*For instance, conscientious health care professionals and organizations know very well that they are not able to meet all the needs of the uninsured people in their communities.

Keen awareness of these characteristics and their influence on ourselves and our health care system will help us to harness their potential for good and limit their potential for harm.

Catholic Social Teaching: The Common Good, Solidarity, and Stewardship

Several principles from the Catholic tradition — the common good, solidarity, and stewardship — are particularly relevant to the individual and public conscience work necessary in the health care reform movement.

The common good recognizes the deep connection between individual well-being and community well-being as well as an unavoidable tension in that relationship. It calls us to organize society so that all individuals are able to flourish. It sees health care as but one human good among many,* all of which contribute to healthy communities. The common good calls us to look beyond concern for ourselves and for our organizations, to solidarity with all others. Respecting that solidarity entails being responsive to the needs of the entire community. Inherent in the common good and solidarity is a tension between the individual and the community. We can honor those important principles and constructively resolve that tension only through hard choices and tradeoffs that keep those important principles in creative tension.

*For example, higher wages and better education and housing.

Stewardship calls us to recognize that all we have in the way of natural and material goods is a gift to be used prudently on behalf of our present community, as well as of those who will come after us. It reminds us that we must be measured in our use of the gifts we are given. It maintains that wealth should never be hoarded; rather, it should benefit the community, not just fortunate individuals who happen to possess it. Those mindful of stewardship recognize their limited claim on goods. They are stewards, not owners, and have a responsibility for the fair distribution of basic goods to the entire community.

Health care professionals and organizations are simultaneously part of the solution and part of the problem. By keeping this interior dialogue alive, in ourselves and in our work communities, we are much more likely to get at the root causes of our unjust health system and to contribute to the larger social movement that brings about more health care justice. Such individual and public conscience work is a lifetime endeavor — because medicine and health care are dynamic realities that constantly need direction and shaping so that everyone will be well served. It is well worth the effort because it holds the promise of both greater personal integration and structural reform.