BY: SARAH E. HETUE HILL; PHILIP J. BOYLE, Ph.D., and VICTORIA CHRISTIAN-BAGGOTT M.B.A., NHA, RAC-CT, NE-C; JIM SHAW, MD, DEBORAH A. BURTON, Ph.D., RN, and SANDRA E. GREGG, M.N., M.H.A.; MARIA GATTO, M.A., APRN, ACHPN, NP, BC-AHN, HNP

EDITOR'S NOTE

Health Progress asked four Catholic health systems to describe their programs of palliative care, including stage of experience, challenges and goals. Here, Ascension Health, Catholic Health East, Providence Health & Services and Bon Secours Health System report.

Ascension Health

BY SARAH E. HETUE HILL

In 2004, Ascension Health began a systemwide look at the state of palliative care. We found pieces in place throughout our system, but when we benchmarked them against 49 cancer centers of excellence around the country, we found we had significant work to do to deliver the robust, interdisciplinary and trans-disciplinary type of palliative care our chronically and seriously ill patients and their families deserved.

We set these goals:

- Establish a systemwide, multidisciplinary palliative care task force. It would include representatives from oncology, cardiology, internal medicine with palliative care expertise, nursing, pastoral/spiritual care, social services/case management, ethics, quality improvement, clinical excellence and finance.

- The task force would: set clear objectives and practical strategies to improve palliative care throughout Ascension Health; develop objective criteria and goals for measurement; and create and distribute tools for successful integration of palliative care in diverse care settings.

- Make palliative care training a priority for health care providers across practice settings.

PILOTS, VISION AND PRACTICES DEFINED

The Ascension Health palliative care task force formed in early 2006 and chose seven pilot sites that served an assortment of geographic and socio-cultural settings. These sites were hospitals that already had established palliative care programs with dedicated full-time employees and palliative care goals and measures.

Between 2006 and 2009, the task force and pilot sites created a definition, vision and graphic illustration of palliative care. They identified leading palliative care practices for across-the-board implementation that addressed specific issues pertaining to facility size and type.

As its standard, the task force used the eight domains of quality palliative care identified in the National Consensus Project's Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care.

They created volume, process and quality measures that examine various aspects of the eight domains. Over the four years that we have collected data, we have seen the following:

- The number of deaths remains relatively static and the number of discharges increases at a steady rate, indicating that we are seeing patients earlier in their disease trajectories and that professionals are understanding that palliative care is not only for persons at the end of life

- The No. 1 reason for consultation requests is for help with patient/family education or for assistance with identifying and addressing goals of care

- Results are positive on all three of our quality indicators for symptom management of pain, dyspnea and gastrointestinal distress, which measure not only responsiveness but also timeliness of response

Two metrics examining structures and processes of care also are showing consistent results for the care responsiveness of our teams. One metric tracks whether palliative care assessments are completed within 24 hours of consult requests, and another tracks whether family meetings are completed with an interdisciplinary team within 48 hours of initial consult. Health ministries are able to use these two measures to show the need for additional full-time employees and/or 24-hour, 7-day-a-week coverage.

Our measure on the spiritual, religious and existential domain, which tracks whether a spiritual assessment is completed by a qualified staff person, showed us we needed to provide more education on charting in this area — a relatively easy fix.

Individual health ministries that are able to track even more data are seeing positive results in many areas such as reduced length of stays and readmission rates, improved clinical outcomes and increased patient and family satisfaction. For example, at Seton Health in Troy, N.Y., the palliative care team sees patients primarily through home health consults resulting in a 30-day readmission rate of 1 percent versus the national average of 20 percent for palliative care-appropriate patients and a 60-day readmission rate of only 3 percent.

Several Ascension Health ministries have significantly increased use of hospice for qualified patients. St. Mary's Hospital in Amsterdam, N.Y. has seen a 60 percent increase in the completion of advance directives, and their patient/family satisfaction ratings are ranked at 4.7 out of 5. They also have seen significant improvements around accurately assigning acuity to patients and moving them to appropriate care, including to inpatient hospice. This work has helped create a significant reduction in the raw mortality rate at St. Mary's.

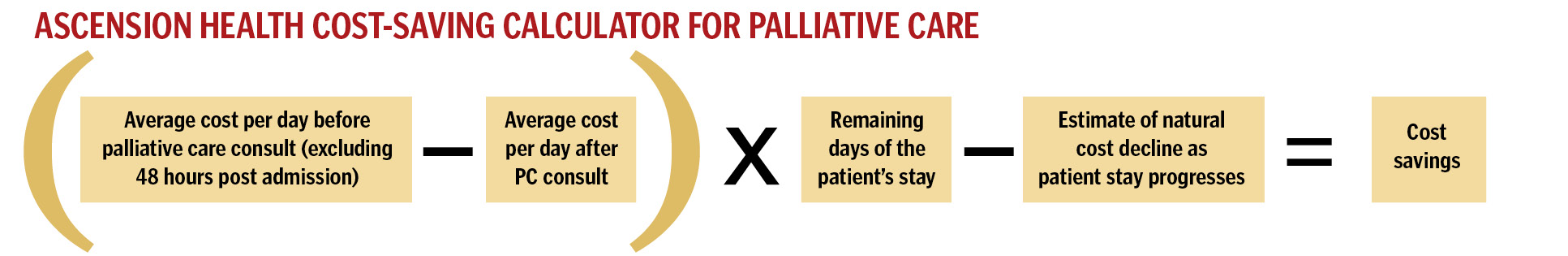

Demonstrating financial feasibility and sustainability of palliative care teams was another important development in this initial phase. Ascension Health ministries developed two different models for measuring financial feasibility and cost savings, and both models have been used successfully to show an increased need for palliative care full-time employees based not only on mission and quality imperatives, but on cost savings. These twin goals of increasing quality and decreasing cost are, of course, important learnings for the implementation of health care reform.

IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES

- Staffing ratios and adequate reimbursement for palliative care teams' work. To deliver the model of care we desire, some teams have had to be creative in working with other departments to make sure all eight domains are addressed for patients and their families. We have engaged with numerous stakeholders to promote advocacy around policy and regulatory change that would provide adequate reimbursement for discussions on goals of care, eliminate the homebound requirement for home health patients with chronic illness, and so on.

- Outmoded medical model. Despite our significant work on culture change and education on palliative care, some of our palliative care teams are still being overused for strictly end-of-life or pain issues. This suggests to us that the old medical model still prevails in some places. The old medical model maintains a strict dichotomy between aggressive, life-sustaining treatment delivered until all hope is lost and delivering palliative care and hospice services only at that point. The old medical model is also built upon the false assumption that palliative care is not also an "aggressive" form of care.

We view palliative care as not merely a service but a model that shifts the way we view care. Our teams have worked diligently on forms of education to counter misunderstandings about palliative care, yet there is still work to be done. We also are involved in several workgroups to enhance the social marketing of palliative care to the public in order to decrease confusion about what palliative care is and how it improves quality of life.

Another related, consistent challenge is late consultation requests for palliative care, or requests that are made within 48 hours of the death or discharge of a patient. We have begun tracking this in several health ministries and are working to complete even more education for creating culture change where this remains a problem.

TAKING IT SYSTEMWIDE

In 2009, we began our transition to Phase II. The first major goal was for all of our acute-care-based facilities to develop plans for establishing a leading practice palliative care model by the end of 2010. They will use the tools and leading practices shared from the pilot sites, as well as from other organizations, for palliative care excellence (including the Center to Advance Palliative Care, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, the Supportive Care Coalition, and others).

The second major goal is to have all of the essential elements of palliative care fully integrated within all Ascension Health ministries by 2015. Creating a model of palliative care delivery throughout the continuum will enable us to provide higher-quality care in more managed and comfortable care settings and reduce the burden on the health care system by addressing and eliminating inefficiencies.

Many of Ascension Health's ministries have significant opportunities for care integration within our own system. In places where we do not have our own facilities beyond the acute-care setting, we will need to work with existing community partners.

A significant portion of our patient population in palliative care — including the chronically ill and elderly — is often among our most vulnerable. We owe these patients and their families better care coordination, improved clinical outcomes, increased quality of life and increased access to person-centered, spiritually centered, holistic care.

SARAH E. HETUE HILL is program coordinator, palliative care initiative, for Ascension Health, St. Louis.

Ascension Health, based in St. Louis, is the nation's largest Catholic and nonprofit health system. Its more than 500 locations provide acute care, psychiatric, rehabilitation, residential care and community health services in 20 states and the District of Columbia.

ASCENSION PILOT SITES

Carondelet Health Network, Tucson, Ariz.

Our Lady of Lourdes Memorial Hospital, Binghamton, N.Y.

Providence Hospital, Southfield, Mich.

Sacred Heart Health System, Pensacola, Fla.

St. Vincent's Health Services, Bridgeport, Conn.

St. Mary's Hospital, Amsterdam, N.Y.

St. Mary's Medical Center, Evansville, Ind.

THE EIGHT DOMAINS OF QUALITY PALLIANCE CARE

- Structure and processes of care

- Physical aspects of care

- Psychosocial and psychiatric aspects of care

- Social aspects of care

- Spiritual, religious and existential aspects of care

- Cultural aspects of care

- Care of the imminently dying patient

- Ethical and legal aspects of care

Source:

Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care

National Consensus Project

Catholic Health East

BY PHILIP J. BOYLE, Ph.D. and VICTORIA CHRISTIAN-BAGGOTT M.B.A., NHA, RAC-CT, NE-C

Catholic Health East (CHE) is a relatively new player in a systemwide approach to palliative care. In 2007, CHE had only three formal, budgeted, palliative care programs with at least one full-time employee. To our own astonishment, in a few short years — and with important mentoring from the Supportive Care Coalition — CHE has made substantial advances in systemwide palliative care programming, not only for those at the end of life but also for those patients who suffer symptoms associated with chronic or life-threatening illness.

Today each of our 11 formal palliative care programs provides several hundred consultations a year. By the end of 2010, all 20 regions within CHE will have three-year palliative care plans in place, and most already have begun their implementation.

What follows is a description of how we got started on a systemwide approach and what we learned.

GETTING STARTED

In 2007, CHE joined the Supportive Care Coalition and their leadership set a new level of expectation for our system. We assessed our palliative care programming through semi-structured interviews at all CHE ministries. In short, the interviews revealed misperceptions and resistance to palliative care — a lack of passion and nerve. To change this culture, we set about making the palliative care case. We formulated an explanation and rationale and aimed for constant reiteration at every level of CHE — including board members and clinicians.

We simply said, over and over, some version of the following: "The public perception of Catholic health care is that it provides compassionate care. Surely all health care should do that, but with Catholic health care's reputation on the line, no person in our ministries should die alone or in pain or while experiencing suffering from any symptom that could be treated and managed effectively through palliative care. Our most important opportunity is to live up to our reputation."

Along with addressing the challenges, we also focused on what we were doing well with the idea of capitalizing on our strengths. We discovered CHE had 25 board-certified palliative care physicians, 10 of whom were employed as hospitalists or as directors of palliative care or hospice programs. In our experience, programs that make substantial advances are championed by a physician leader who has gained the confidence of other physicians in the institution. Thus our message to the ministries that already had intensivists and hospitalists was to encourage them to build on that core group by showing hiring preference to those with backgrounds in palliative care. We also urged them to encourage non-board-certified physicians to sit for board certification in hospice and palliative medicine before 2012, when training requirements are due to change.

We discovered that two programs (St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne, Pa. and St. Mary's Health Care System in Athens, Ga.) are led by palliative care nurses and that these programs perhaps eased concerns of referring physicians who might otherwise have believed they would lose patients to palliative care physicians. Our interviews also revealed that medical students at Saint Joseph's Health System in Atlanta, Ga., have been used both to extend the reach of palliative care and to cultivate prospects for the needed board-certified palliative care physicians.

We have found inventive collaboration with external palliative care and hospice programs extends the efforts of palliative care programming. Several institutions have partnered with hospice, either bringing it inside the institution with dedicated inpatient hospice units or closely partnering through bridge programs. In some instances, community hospices offer not only end-of-life care but also palliative services to acute care patients. We also have devised a creative use of trained pastoral care or hospice volunteers who provide a comforting presence to those who are dying, ranging from the national "No One Dies Alone" program at five of our ministries to a program of telephone pastoral visits staffed by retired women religious for Mercy Home Health of Southeastern Pennsylvania.

We discovered and encouraged one crucial element of systemwide programming, namely, care for the caregivers. Most notably, four ministries conduct quarterly Schwartz Center Rounds underwritten by an annual grant. The rounds provide an interdisciplinary forum where caregivers discuss difficult emotional and social issues that arise in caring for patients.

Outside this formal programming, several spiritual care departments are present at or near the deaths of all patients, ministering not only to patients and families but also to the caregivers who are often emotionally and spiritually affected by the death.

FUNDING AND REIMBURSEMENT

By networking with institutional members of the Supportive Care Coalition, CHE palliative care services developed a range of programming, most relying on the creative use of staff, volunteers and external partners rather than extra funding. Certified palliative care physicians lead most CHE palliative care programs; two are led by nurses who provided over 1,000 consultations last year. Volunteers, especially those who stay with actively dying patients, expand our programs' reach. Equally noteworthy, hospice programs not owned by CHE often offer important partnerships by providing support in palliative care and end-of-life services.

Reimbursement continues to be a significant administrative challenge since only physicians can bill for visits. However, successful palliative care programs require other professionals, including nurses, social workers, masseuses, art and occupational therapists and chaplains.

For example, many of our sites regularly use such innovative palliative programming as healing touch, art therapy, pet therapy and yoga. BayCare Health System's Morton Plant Hospital (Clearwater, Fla.), provides teddy-bear therapy where the use of the teddy bears has a calming effect not only on dementia patients, but also on patients who are restless and in distress. For children who have lost loved ones, one site provides a camp experience.

To support these professionals, existing programs have relied on external grants and hospital foundations. A few of the programs, most notably Sisters of Providence Health System, Springfield, Mass., and Saint Joseph's Health System in Atlanta, are actively tracking cost reduction associated with palliative care services, such as hospital readmissions, reduction in length of stay and other reductions in expenses for long stays in ICU or other critical care units.

THE WORK AGENDA

The innovative programs and the challenges reported suggest opportunities for growth within CHE including:

- Effectively partnering with local hospice for palliative care services

- Aggressively seeking grant funding

- Successfully training and engaging volunteers for "No One Dies Alone" programs

- Identifying and cultivating physicians who could sit for the palliative care board certification before 2012. Board-certified palliative care physicians who secure certification before 2012 will not be required to attend a residency or fellowship.

- Providing system support to regional health corporations to continue to develop and implement palliative care programs.

- Identifying leading practice for development of palliative care suites.

- Enhancing care for the caregiver programs.

In the meantime, CHE has developed a pilot program consisting of a six-part webinar to be offered to day, evening, and night shifts in fall 2010. In collaboration with Consolidated Catholic Health Care, these webinars, which are CME- and CEU-ready, will be made available nationally in a way similar to CHE's existing programming in ethics and spiritual care.

PHILIP J. BOYLE is vice president, mission and ethics and VICTORIA CHRISTIAN-BAGGOTT is vice president, clinical improvement for the Continuing Care Management Services Network (CCMSN) at Catholic Health East, Newtown Square, Pa.

CATHOLIC HEALTH EAST is a multi-institutional Catholic health system based in Newtown Square, Pa. The system includes 34 acute care hospitals, four long-term acute care hospitals, 25 freestanding and hospital-based long-term care facilities, 14 assisted-living facilities, four continuing care retirement communities, eight behavioral health and rehabilitation facilities, 37 home health/hospice agencies and numerous ambulatory and community-based health services located within 11 Eastern states from Maine to Florida.

CHALLENGES

We found the challenges to launching and sustaining a systemwide palliative care program to be divided among clinical, administrative and cultural barriers.

- Clinically, the greatest barrier is the continued misunderstanding of appropriate pain and symptom assessment and management, not only at the end of life, but also for chronically ill patients — a challenge that exists across the continuum of care

- Nurses and physicians alike do not commonly distinguish palliative care from hospice care, and both groups are undereducated about appropriate pain and symptom assessment and management

- Physicians are slow to recognize that the benefits of early referrals and collaboration with the palliative care team can facilitate difficult and critical conversations and decisions with the patient and family

Providence Health & Services

BY JIM SHAW, MD, DEBORAH A. BURTON, Ph.D., RN and SANDRA E. GREGG, M.N., M.H.A.

Starting in 2007, a group of Providence mission and clinical leaders made the case for a uniform, systemwide set of palliative care services. The chief medical officer and chief nursing officer agreed and co-sponsored a palliative care initiative as a clinical and quality priority. They also gave a boost to the original palliative care leadership group by adding multidisciplinary clinical and operational participants.

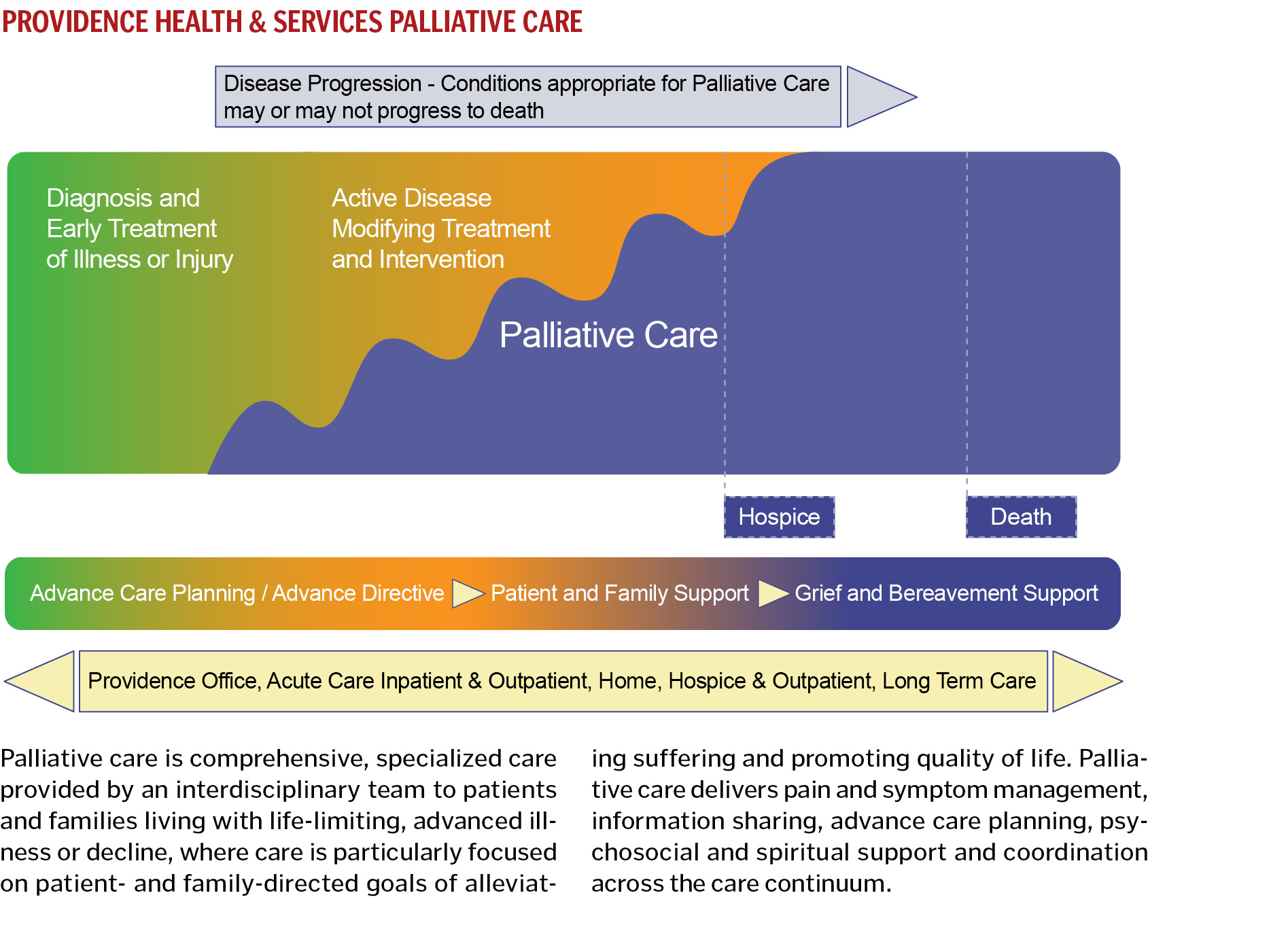

The first step was to conduct a comprehensive gap analysis across the system to measure palliative care services against national standards and to look for shortfalls. The 2009 analysis included both acute and community-based services. Based on those findings, more than 50 representatives from a wide range of palliative care teams and services came together for a two-day summit. Their primary goal was to arrive at a single Providence palliative care definition, model, minimum specifications and key metrics. The very broad multidisciplinary set of participants — physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, finance and mission leaders, administrators and analysts — enriched the process and further generated enthusiasm for what would become the Providence brand of comprehensive, continuum-based palliative care.

The summit generated commitment both for a uniform palliative care model and a level playing field between acute and non-acute palliative care services. Building on best practices discerned from participation in the Supportive Care Coalition, Providence expanded palliative care support across the entire care continuum and recognized the importance of offering palliative care services from the time of diagnosis.

Using a disciplined, consensus-building process, the group arrived at a definition for Providence palliative care.

Working from that definition, summit participants created and adopted minimum specifications to assess the extent to which palliative care is or is not being delivered. They also created clinical, financial and process-focused metrics, including:

- Palliative care providers will formulate, use and regularly review a timely care plan based on a comprehensive interdisciplinary assessment of the values, preferences, goals and needs of the patient and family

- Palliative care providers will measure and document pain, dyspnea, constipation and other symptoms using available standardized scales

- 30-day readmission and emergency department re-visit rates will be tracked and reported for all palliative care patients

REGIONAL ACCOUNTABILITY

As part of their 2010 strategic planning, the four Providence geographic regions were charged with identifying and closing palliative care service gaps in their local markets. The systemwide palliative care leadership team continued to act as coordinator in connecting region-specific quality plans and accountabilities. The team also began strategic planning for the next steps: competency assessment; developing a physician fellowship program and other educational efforts; credentialing; consultation support; and establishing systemwide governance for palliative care.

SYSTEM STRATEGY AND DIRECTION

Until recently, the organization could correctly be described as a traditional health system that honored local subsidiarity and autonomy in clinical care delivery. However, over the past five years, Providence has evolved, adopting a "One Ministry Committed to Excellence" strategy. For clinical care, that means reducing unnecessary variation in care delivery through standardizing clinical processes where appropriate and when supported by evidence.

As the regions became engaged in their planning, Providence took two major strategic steps towards accelerating the advancement of palliative care as a permanent pillar of clinical excellence and mission accountability.

One step was deciding to roll out a single electronic medical record system across Providence, in all care settings. Preparing for effective and efficient implementation of electronic medical records is driving rapid standardization of both clinical content and care delivery processes.

The second step was selecting palliative care as a program to be coordinated and supported systemwide. It is one of four pilot programs Providence launched to give certain clinical services a more formal collaborative structure. We chose palliative care because of its multidisciplinary leadership commitment, its mature and disciplined definitional and reporting components and its breadth of services.

PROGRESS TO DATE

As the developmental phase of our palliative care journey has gained momentum since 2009, Providence has collected rich anecdotal and experiential evidence that the culture is shifting dramatically.

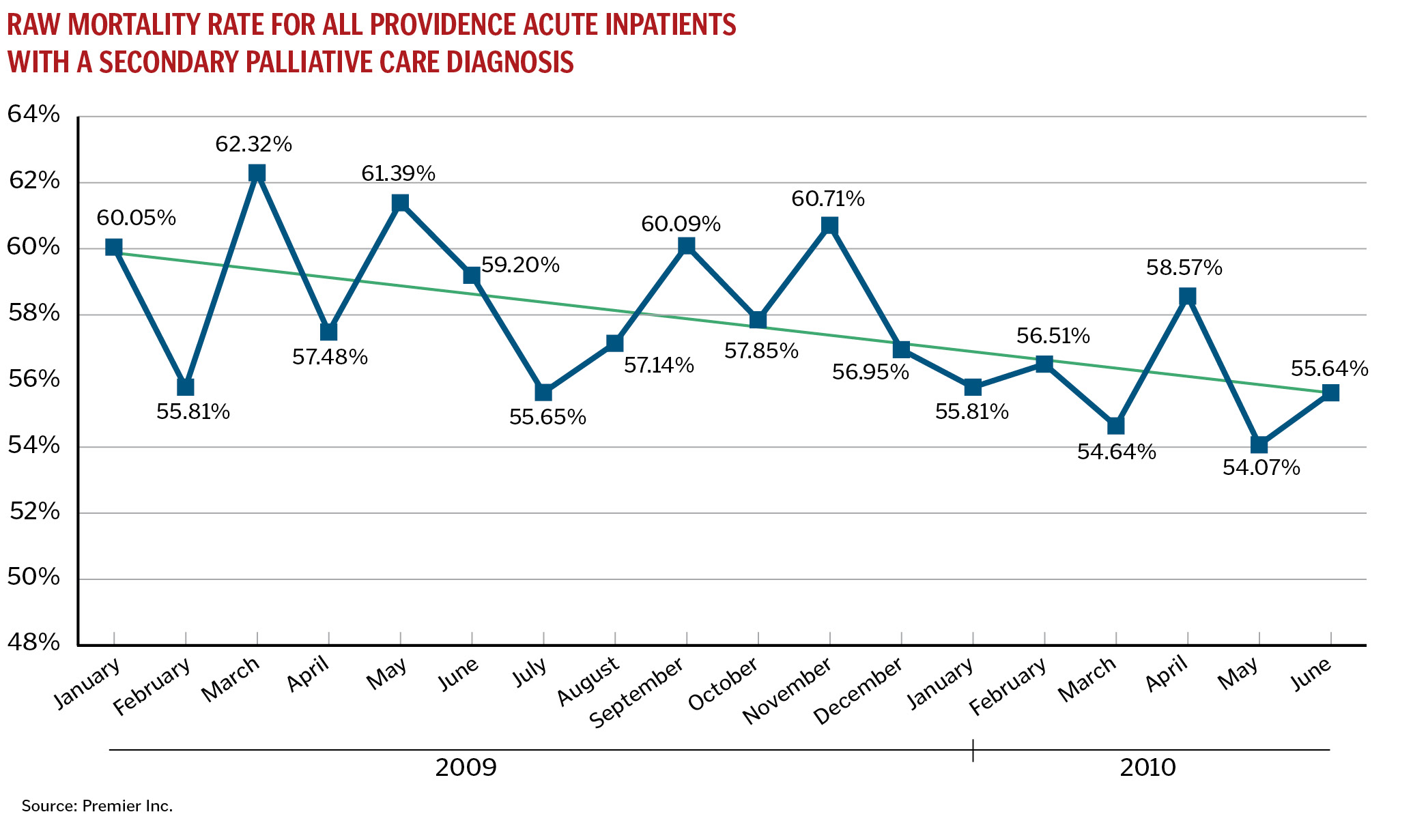

More recently, performance data have revealed a favorable effect on care outcomes. The table above summarizes system-level raw mortality rates for palliative care patients for the period January 2009 through June 2010, the very segment during which this work was launched. The downward trend is mirrored in identical analyses performed for each of the four Providence regions: Alaska, Washington/Montana, Oregon and California.

This early evidence of the impact of our work is encouraging. Most of all, we attribute our early clinical success to two essentials: leadership commitment and deep teamwork.

The focus for 2011 will be to continue clinical program formation and to further the spread and adoption of best practices in palliative care across all Providence ministries. In addition, we will create a strategic quality plan for palliative care.

CONCLUSIONS

Here are some of the lessons learned and barriers overcome:

- Palliative care develops and thrives when positioned within the organization as a key driver of quality

- Excellence in palliative care depends on a comprehensive "plan of care" implemented consistently across the entire care continuum

- Coordination and standardization of palliative care services require multidisciplinary clinician engagement and support, as well as program leadership and sufficient human and project management resources

Our palliative care journey began with the heritage and vision of our founders, the Sisters of Providence. Staying true to the groundwork started by the sisters is a key part of driving this mission-based work. On behalf of the most vulnerable patients and their families, Providence is committed to increasing access to palliative care services across the continuum of care.

JIM SHAW is medical director at Providence Center for Faith and Healing and supportive care physician for Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center, Spokane, Wash.

DEBORAH A. BURTON is vice president, chief nursing officer and SANDRA E. GREGG is director of strategic nursing initiatives at Providence Health & Services' system office, Renton, Wash.

PROVIDENCE HEALTH & SERVICES is a not-for-profit Catholic health care ministry comprising 27 hospitals, numerous non-acute-care facilities and physician clinics, a health plan, a liberal arts university, a high school and many other health, housing and educational services. The health system spans five states — Alaska, Washington, Montana, Oregon and California — and its system office is located in Renton, Wash.

Bon Secours Health System

BY MARIA GATTO, M.A., APRN, ACHPN, NP, BC-AHN, HNP

Bon Secours Health System's task force on palliative care has its roots in the system's 1992 statement on care of the dying, followed by a quality plan. The task force, made up of representatives from mission services, the corporate level and local systems, ran demonstration projects from 1999 to 2004 that created and tested sites of palliative care around the system.

In 2005, I joined Bon Secours as director of palliative care to help create a systemwide, standardized and clinically comprehensive program. That same year, we established an interdisciplinary committee to create a palliative care charter and conduct a needs assessment/gap analysis.

We determined Bon Secours' top palliative care issues to be inconsistencies and a lack of standardization. Specifically, the study showed inconsistencies in palliative care policies and procedures, in compliance standards, documentation, outcome metrics and data information systems. We also found a lack of standardization in core and interdisciplinary palliative care teams, program models and educational requirements.

We presented the results of our research to corporate and local system leadership board quality committees and executive committees. That led to a commitment to implement standardized palliative care services throughout the system.

STEPS TO STANDARDIZATION

In 2006, the Bon Secours Health System named palliative care as a core element in its strategic quality plan for fiscal year 2006. That meant palliative care at Bon Secours was presented for the first time as different from hospice care and more than a consultative bedside service.

The health system then created a systemwide advisory council focused on developing budgetary support for palliative care, standardizing policies and procedures, developing palliative care documentation and incorporating palliative care into standardized electronic data collection.

'FORM FOLLOWS FINANCE'

Recognizing that form follows finance, the palliative care advisory council recommended that each local system develop an annual budget to support palliative care services within its operations. Local systems were urged to budget funds to support palliative care teams, palliative care education and a palliative care measurement system. As a result, all Bon Secours local systems presently have line items within their budgets to support palliative care services.

The advisory council appointed an ad hoc committee that spent a year creating a systemwide manual for standard palliative care policy and procedure. The committee tapped local system leadership, administration, physicians, nursing and medical executive committees for their input. At the corporate level, the governance, sponsorship and legal departments reviewed the draft content. Once they reached consensus, the policy and procedure manual went systemwide.

The manual is consistent with the Center to Advance Palliative Care guidelines, The Joint Commission standards and the National Quality Forum palliative care compliance standards.

MEASURING AND MONITORING

The advisory council recognized Bon Secours needed a palliative care documentation system to measure quality of care as well as to monitor compliance with national palliative care standards.

Bon Secours Hampton Roads Health System in Hampton Roads, Va., launched a pilot program using electronic medical record keeping that integrated Center to Advance Palliative Care screening tools, palliative care referral communication, processes, work lists, automated reports and a progress note format that palliative care practitioners could use. This system also allowed the practitioner to remotely review documents such as dictated histories and physicals and consultant reports from organizations that use paper charts.

Meanwhile, Bon Secours' ConnectCare, a powerful electronic medical records system, was being developed and is now being implemented in acute care and ambulatory settings. It provides an integrated, advanced system of clinical information and evidence-based practices.

The ConnectCare palliative care team, consisting of experts throughout the health system, used the documentation, research, screening tools and guidelines and the supportive guidance from the National Institutes of Health Director of Pain and Palliative Care Service to create a customized palliative care documentation system and order sets in ConnectCare.

To address data needs, the palliative care advisory council in 2008 piloted the Palliative Care Identifier Project at Bon Secours St. Francis Health System, Greenville, S.C. The project developed an electronic health information system code that identifies palliative care patients once the attending physician writes an order for a palliative care consult. Palliative care data reporting capabilities continue to expand throughout the Bon Secours system to report utilization, operational and financial outcomes.

CURRENT SYSTEMWIDE STRATEGIES

The system's current strategic quality plan, covering fiscal years 2010 through 2012, includes palliative care as a key element of such systemwide initiatives as dashboard reporting, mortality and "Zero Preventable Deaths," "clinical transformation" and the system's Center for Clinical Excellence. "Zero Preventable Deaths" is a project to reduce harm to our patients. Initial findings included lack of recognition of sepsis and lack of planning that focused on earlier palliative care services, especially with chronic disease and the ICU settings.

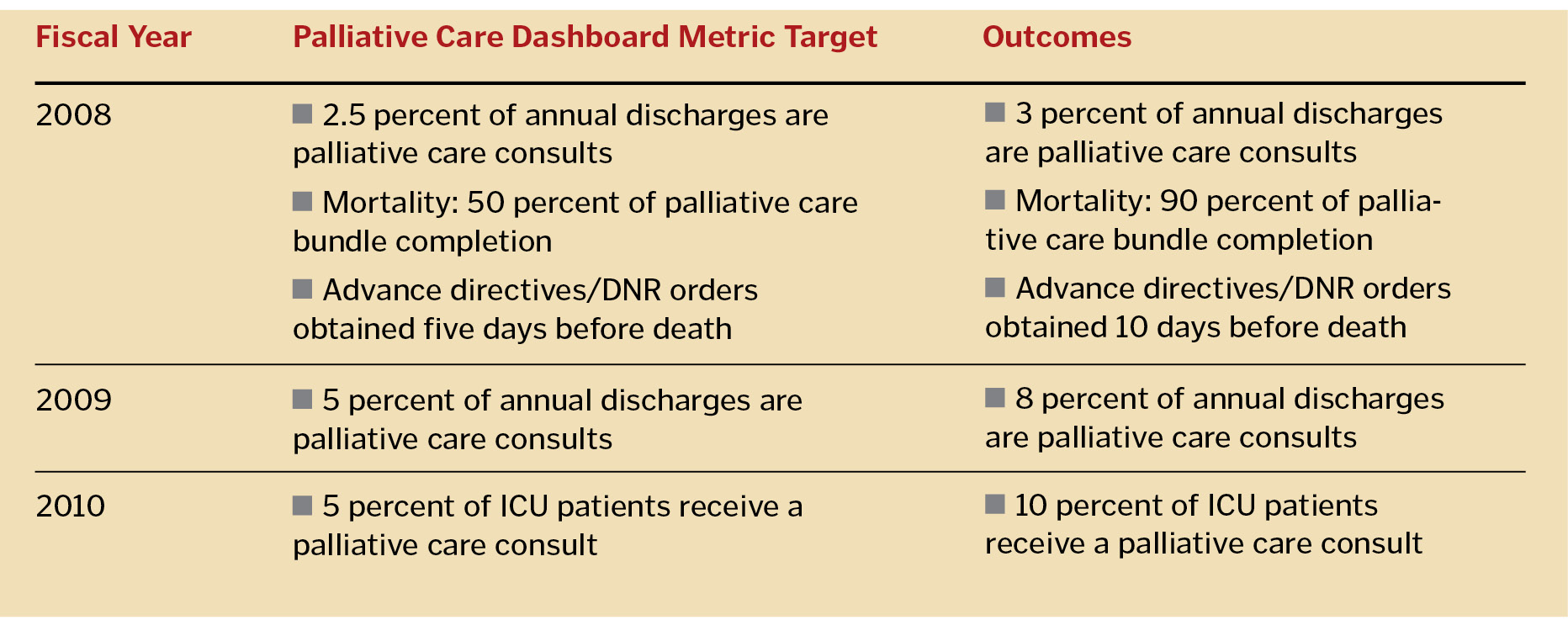

Dashboard reporting is a monthly review of each local system's performance on standardized metrics. The metrics cover multiple elements in the categories of community benefit, employee development, clinical excellence, growth and finance. Each year, a different palliative care metric is included as part of the reportable outcomes of clinical excellence. Over time, the local systems have demonstrated improvement in palliative care indicators. The table below shows the actual dashboard indicators Bon Secours Health System used for palliative care.

CONCLUSION

"Zero Preventable Deaths" was Bon Secours' first systemwide initiative to identify and provide palliative care as part of the efforts to recognize anticipated deaths and to eliminate unanticipated deaths. The initiative used tools from the Institute for Health Care Improvement.

We found local systems consistently failed to recognize, identify, plan and provide palliative care/hospice care services to appropriate end-of-life patients. In response, we initiated several collaborative improvement projects, processes and outcome measurement action items, all of which contributed to significant reductions in the mortality index. For example, we included palliative care teams as part of the mortality review process and established outcome targets in the ICU for palliative care consultation.

"Clinical transformation" is Bon Secours Health System's comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach that seeks to improve quality through innovation and process improvement. The palliative care initiative has demonstrated financial outcomes, as well, that translated into $4 million savings in 2008 and improving the quality of care.

The recently established Center for Clinical Excellence sets standards for practice excellence, and palliative care is a key element. The center's major focuses include practice excellence, care delivery redesign, a culture of safety, clinical education, leadership development and leveraging technology.

For nearly 20 years, Bon Secours Health System has actively sought to improve care of the dying. Over the past five years, the system has made dramatic, measurable improvements in the use and effectiveness of palliative care throughout the continuum of care. Palliative care at Bon Secours is becoming a standardized and clinically comprehensive program that has demonstrably improved quality of care, reduced costs and improved mortality rates.

MARIA GATTO is a board certified, advanced practice, palliative care and holistic care nurse practitioner. She is director of palliative care for Bon Secours Health System, Marriottsville, Md.

Bon Secours Health System, based in Marriottsville, Md., owns, manages or joint ventures 18 acute care hospitals, five long term care facilities, four assisted living facilities, 14 home care and hospice services and other health care facilities in seven states located primarily on the East Coast.