BY: EDWIN TREVATHAN, MD, M.P.H.

For all who work in Catholic health care, a commitment to people who are poor, vulnerable and socially marginalized is a manifestation of a commitment to show the love of God to the world and an expression of the pursuit of justice in an unjust world. In this complex and transformative time in U.S. health care, new opportunities abound to sustain and expand these commitments, thus strengthening our identity and our mission as Catholic institutions, along with our financial positions, by fostering new strategic partnerships with community organizations.

With the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), we must improve health care outcomes and reduce costs while we care for people who are poor, who have multiple chronic diseases and who are at the highest risk of complications. Many of the major determinants of poor health outcomes, and of high health care costs, are found outside the walls of our hospitals and clinics. Only by improving the baseline health of patients before they enter our hospitals, and by enhancing their health after they are discharged, will our health systems and hospitals be able to maintain a commitment to the vulnerable while remaining financially viable. As a result, health care leaders today must view their domain of influence much more broadly than their predecessors, as they partner with new organizations and invest in wellness and health promotion at the community level. Strategic financial prowess in the boardroom will be essential, but political and collaborative skills at the community level will become the new currency on which health care systems will trade.

Consistent with the ACA's revision of the tax-exempt status for nonprofit hospitals (Section 9007), hospitals and health care systems are required to conduct community health needs assessments at least once every three years. Then, once health needs of the community are identified, the programs developed and implemented to address them, if "transparent, concrete, and measureable," may be considered as community benefit investments by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS Policy 2011-52).1, 2 While findings of community health needs assessments and information gathered from community representatives will vary between high-risk communities, most poor communities in the United States have fairly consistent and predictable health needs that may be addressed by public health approaches and implemented via community benefit programs.

In an effort to demonstrate possible approaches to addressing an identified public health problem, this article offers examples of public health interventions to improve maternal and child health — interventions that can reduce costs while carrying out the mission of Catholic health care. The methods used for defining populations for community health needs assessments, that is, for establishing community relationships and partners and implementing interventions to improve infant and child health, are similar to methods that might be used for improving health outcomes for adult conditions.

DEFINING THE POPULATION SERVED

When doing a health needs assessment, health systems, hospitals and clinics should first identify the geographic area and the specific populations served by their institutions. For example, public health interventions aimed at improving maternal and childhood health should focus on those mothers and children that some hospitals have attempted to avoid — those with the worst health outcomes, who fail to utilize appropriate preventive services, who tend to have high emergency room utilization and high rates of outcomes associated with poor social standing, such as prematurity and infant mortality. This population is also likely to have high rates of asthma admissions, low vaccine coverage and high rates of preventable hospital readmissions. These geographic areas are also likely to be those where other adults with the worst health outcomes live and work.

Partnerships with state or local health departments, and with a school of public health in the region, may allow a health system to best identify the neighborhoods where patients with the worst outcomes reside. Once the populations for public health interventions have been identified, the stage is set for a community health needs assessment.3 These assessments, along with community-based participatory research, have rapidly evolved into a highly specialized field with specialized methods. Health system leaders may benefit from consulting experts in the methods of engaging the community members, design of the assessment instrument and in the analysis of the data.4

PLACE-BASED INTERVENTIONS

In most communities the people most likely to benefit from public health interventions to improve maternal and child health are those with the least access to reliable transportation to a health care facility. Competing immediate priorities, poor health literacy, concern that missing a day of work will result in loss of income and denial of health risk all make it unlikely that future high-risk patients will seek elective preventive interventions. Health care professionals will have to take interventions to their targeted populations where they live, where they work, where they play and where they worship. Focusing on a single location in a community is rarely successful; health professionals should plan on working with employers, churches, local housing authorities and other local gathering places.

Once the neighborhoods where poor, at-risk people live have been identified, the next step is to find out where they work. Remember that contrary to popular stereotypes, most of the poor in America work as much as they can and move in and out of poverty as their job, health and family situations fluctuate. Hospitals can partner with local community leaders to help make contact with low-income employers. Once they understand that you are offering them an opportunity to improve the productivity of their workforce by improving their employees' health (and the health of their children), employers will likely be enthusiastic partners for both conducting a community health needs assessment and for implementing public health interventions. In-kind contributions from employers (e.g., space for public health programs in the workplace) can reduce costs and improve participation rates.

Leaders in churches and other places of worship in poor communities can be especially helpful in reaching the most underserved and the vulnerable citizens, who often do not trust health care authorities. Engaging the local pastors, priests and religious leaders can be among the most productive strategies. Historically, leaders of local churches have implemented some of the most effective health education, nutrition and vaccination programs and have become the face of health interventions to their communities. These same local places of worship often have available space, allowing interventions to be placed closer to target populations.

Partnering with local businesses and places where at-risk patients shop and play can be especially rewarding. Local YMCAs and similar organizations, beauty parlors, barber shops, bowling alleys and even pool halls can be effective partners for reaching at-risk populations. Local schools and community colleges likewise are critical partners for many public health interventions.

Especially important are partnerships with local grocery stores. First, people on the edge of poverty may work in these stores. Second, in some communities these stores are often gathering places on nights and weekends and allow for distribution of health information. Finally, relationships with these stores over time can lead to making healthier food choices available to poor communities, especially when store owners are brought face-to-face with the poor health outcomes in their community that are associated with poor nutritional choices and with demands for better choices from community leaders and organizations.

PARTNERS AND COMMUNICATIONS

Establishing community relationships and partners for public health interventions takes time. More significantly, thinking of health outside the walls of the institution as part of the Catholic health care mission and its sphere of influence will challenge some of the most experienced managers. Yet the work that health care leaders do both inside and outside of organizations to develop community-based health interventions is well worth the time and the effort. Once a health system demonstrates the power of community-based health interventions, there will be no going back to the more limited view of an institution's role.

Those institutions that are just beginning to work in the poorest communities should not be surprised if they are not welcomed or perhaps are even openly distrusted. It will take time and effort to carefully develop, nourish and sustain relationships with community groups that lack experience partnering with health care organizations or may have had prior bad experiences with the health care system. Professionals should be prepared to spend time listening to the stories of people who, in spite of the best intentions, have felt unwelcomed by or have lacked access to health care facilities. Coordination with local health departments and local federally qualified health centers is important, too, because the goal is to complement, and not compete with, these organizations. A partnership with a local or regional school of public health may be helpful, as these schools often have experts in health communication with established relationships in these communities.

Remember, health care organizations must be "all in" for the long term. To enhance local cultural credibility, and to send the signal that this will be a long-term commitment, it may be good strategy to hire a respected health worker from the local community or neighborhood to champion community-based interventions.

Sharing the results of the community health needs assessment with the local community, at meetings in the community, and collecting input on implementation of interventions can help develop trust and facilitate buy-in for interventions. Local community ownership and local branding of interventions is difficult for some health care executives who feel a need for their institution's name and logo to be front and center. However, in a culture where large institutions are distrusted, placing a local face and a local community name ahead of the hospital or clinic name can send important signals to the community and ensure support from local leaders, who will then champion joint interventions more effectively.

Reporting progress of public health interventions in local church bulletins and community newspapers and having local residents distribute fliers in strategic locations can keep the community engaged. The communication materials must be appropriate for the local education level, culture and beliefs. It is important, therefore, to use health communications experts who know the local culture rather than the in-house marketing staff, who are typically oriented towards communicating with more affluent populations, or even physicians.

Local engagement and partnering with other interested groups are among strategies that bring the principles of Catholic social teaching to care of underserved populations. Not only do they align with the goals of health reform and the specific requirements of the ACA, they provide new opportunities for Catholic health care organizations to live out their mission in our world.

EDWIN TREVATHAN is a pediatric neurologist and epidemiologist. He is dean of the College for Public Health and Social Justice and professor of epidemiology, pediatrics and neurology at Saint Louis University, St. Louis.

NOTES

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Public Law 111-148, 111th Cong. (March 23, 2010), S 9007.

- U.S. Internal Revenue Service, "Notice and Request for Comments Regarding the Community Health Needs Assessment for Tax-Exempt Hospitals," Notice 2011-52, Internal Revenue Bulletin: 2011-30 (July 25, 2011).

- Meredith Minkler and Nina Wallerstein, eds., Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: Process to Outcomes (San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons, 2008).

- Michael Bilton, "Assessing Health Needs: It's a Good Strategy," Health Progress 93, no. 5 (Sept.-Oct. 2012): 78-79.

THE CASE FOR INVESTING IN MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH

INTERVENTION PROGRAMS IS STRONG

Almost 1 in 4 (23 percent) children in the U.S. live in poverty. According to UNICEF, among the world's 35 wealthiest countries only Romania has a higher percentage of children who are poor.1 Further, the U.S. infant mortality rate is among the highest in the developed world (Figure 1). Infants born to African-American mothers in the U.S. suffer infant mortality rates more than twice that suffered by infants born to white women in the U.S. (Figure 2). The mortality rate among infants born to African-American women in the U.S. is similar to infant mortality in many developing countries. For example, infant mortality among African-Americans in the U.S. is worse than in Malaysia, Costa Rica or Guam, and similar to Bosnia and Serbia, according to the Central Intelligence Agency's World Factbook 2011.

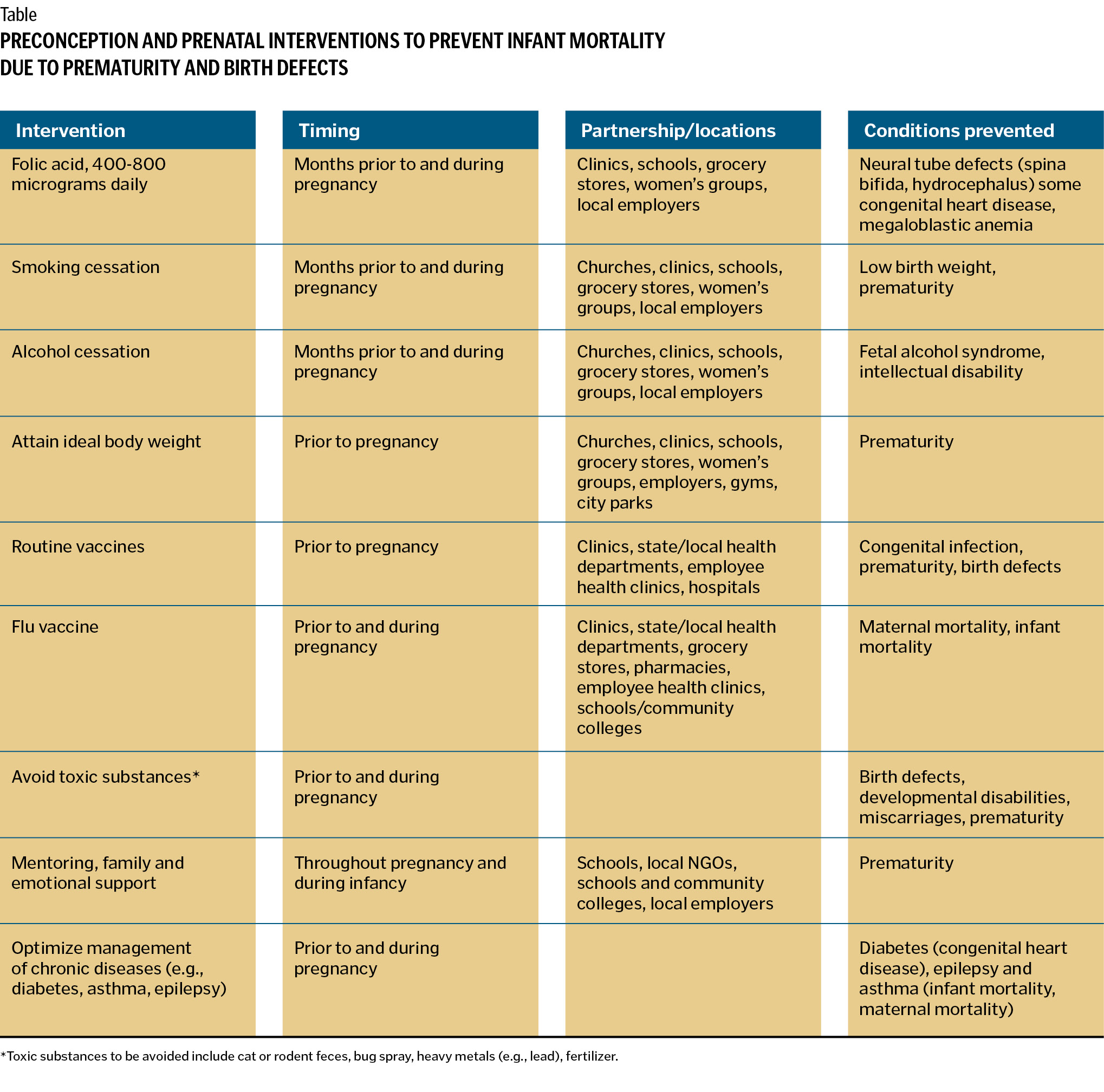

Prematurity and birth defects (e.g., congenital heart disease, neural tube defects) constitute the major contributors to infant mortality in the U.S. Rates of prematurity in the U.S. have increased over the past 20 years. Rates of prematurity among infants born to African-American mothers are twice as high, and rates of early preterm births are 3 to 4 times as high as other racial and ethnic groups in the U.S.2 Likewise, infant mortality due to congenital heart disease is significantly higher among African-American than among white infants.3 Rates of neural tube defects (spina bifida, hydrocephalus) are higher among infants born to Hispanic mothers than among African-American or white mothers, perhaps due to less access to folic acid-fortified grain products and lower rates of folic acid supplementation.4

The cost of caring for a single premature child in a newborn intensive care unit (NICU) ranges from $51,000 to over $1 million per child, with the annual cost of caring from our nation's 500,000 preterm births per year estimated at more than $26 billion.5 The usual hospital or health system response is usually to cover the costs of the growing number of underinsured premature neonates, and some hospitals quietly develop unpublished strategies to limit underfunded neonates in their institution. Yet the negative impact of poverty on girls, young women and their children and their health can be reduced by some well-established public health interventions that Catholic health systems and hospitals, working with community partners, are well-positioned to implement.6

The window of opportunity for preventing many birth defects and improving newborn outcomes tends to close before most women realize they are pregnant. Over half of pregnancies in the U.S. are not planned. Typically by the time most women attend their first prenatal appointment with their obstetrician, the time to prevent neural tube defects and congenital heart defects, for example, has long passed. Preventing birth defects and prematurity, and therefore having a major positive impact on infant morbidity and mortality, requires that we improve the health of girls and young women of childbearing age before they become pregnant — often before they come in contact with clinics and hospitals.

Vaccinations, elimination of iron deficiency anemia, optimal folic acid supplementation, achieving an ideal body weight with good nutrition, smoking and alcohol cessation, and multivitamin use and elimination of the use of street drugs are all important factors in achieving the best preconception health. Women with sexually transmitted diseases, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, epilepsy, hypertension, arthritis and eating disorders should optimally have these disorders treated prior to pregnancy. Specific toxic substances, such as cat or rodent feces, bug spray, heavy metals, fertilizer and some synthetic chemicals can be especially risky for the unborn child, and exposure risks should be eliminated in the home and work environment prior to pregnancy. Finally depression and other disorders of mental health should be effectively treated prior to pregnancy.7

Optimizing the health of high-risk girls and young women prior to pregnancy requires partnerships with community organizations with access to these young women and community-based staff who can best implement preconception health programs. Hospitals and health systems that partner with high schools, community colleges, churches and places of worship and employers of young women have significant opportunities to improve birth outcomes by improving preconception health

Providing a safe and nurturing environment for poor women, when pregnant, with mentors and caregivers has demonstrated promising effects in preventing prematurity and infant mortality. For example, Birthing Project USA provides each pregnant woman with a "sister" or mentor early in pregnancy. The mentor, typically an experienced older woman from the local community who has been trained in preconception health and prenatal health, provides health advice, mentors the pregnant woman through the pregnancy, encouraging healthy behavior choices, and assures a safe and nurturing environment. The mentor likewise helps the pregnant woman navigate her way through the health care system. Birthing Project programs in Nashville and Memphis, Tenn., New Orleans and other cities, for example, have been associated with major reductions in infant mortality and prematurity.8

Preparing pregnant women to breast-feed can improve the odds that exclusive breast-feeding is maintained for the first 6 months of life and then combined with complementary foods until 12 months of age as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics.9 Breast-feeding reduces morbidity from a variety of childhood illnesses and improves health overall. Furthermore, breast-feeding neonates in the NICU may reduce duration of hospital stays, more than paying for investments in preconception health and prenatal programs that emphasize breast-feeding.

Some health systems are now beginning to provide cell phones, or even smartphones, to low-income pregnant women in order to enhance communication with health care providers. Smartphones now offer the potential to deliver customized health messages regarding healthy living during pregnancy and child care. These interventions, perhaps in combination with mentoring projects that enhance preconception and prenatal care programs, may help reduce infant mortality and morbidity among high-risk populations.

Under health reform, Catholic hospitals and health systems, by efforts to improve maternal health, have expanded opportunities to solidify their commitment to social justice, while improving the health of their most vulnerable patients and improving their financial status through community-based public health interventions with carefully selected partners.

NOTES

- Peter Adamson, Innocenti Report Card 10: Measuring Child Poverty (Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, May, 2012).

- Robert L. Goldenberg and Elizabeth M. McClure, "The Epidemiology of Preterm Birth," in Preterm Birth: Prevention and Management, Vincenzo Berghella, ed. (Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010): 22-38.

- Suzanne M. Gilboa et al., "Mortality Resulting from Congenital Heart Disease among Children and Adults in the United States, 1999-2006," Circulation: American Heart Association 122 (Nov. 22, 2010): 2254-2263.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, "CDC Grand Rounds: Additional Opportunities to Prevent Neural Tube Defects with Folic Acid," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59, no. 3 (Aug. 13, 2010): 980-984.

- Richard E. Behrman and Adrienne Stitch Butler, eds., Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2007).

- "Preconception Care," supplement to American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 199, no. 6B (2008): S257-S396.

- Kay Johnson et al., "Recommendations to Improve Preconception Health and Healthcare in the United States," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55, RR06, (2006):1-23.

- www.birthingprojectusa.org, (accessed Oct. 22, 2012).

- Joan Younger Meek, ed., with Sherrill Tippins, American Academy of Pediatrics New Mother's Guide to Breastfeeding, 2nd Edition. (New York: Random House, 2011).