BY: TERRENCE F. CAHILL, EdD, FACHE, and LAURA E. CIMA, RN, PhD, NEA-BC, FACHE

Andrea Eberbach

Sooner or later, all of us become consumers of health care services. What if, when we are a patient in a hospital or other health care setting, there are not enough qualified, competent nurses to care for us? Or what if the nurses around us don't work together as an effective team?

Research confirms there is more potential for medical errors when there are staff shortages and stress associated with excessive workloads.1 And in today's complex health care delivery systems, very little can be accomplished by just one professional. For the best medical outcome, we need effective teamwork, multiple individuals collaborating to give us optimal care.

Unfortunately, these are real concerns. Nursing shortages are increasing, as are tensions on the job, and both are exacerbated by a significant shift in age groups that make up the health care workforce.

GENERATIONS

Viewing health care workers and nursing services through a generational lens is a fairly recent phenomenon, and it mirrors the arrival of millennials — people born between approximately 1981 and 2005 — in health care careers.

Think of a generation as an age cohort or group that grows up experiencing the same major events, cultural trends, music, movies, TV shows and the like for the first 20-25 years of their lives. Because of the early life experiences they have in common, members of the age group tend to have similarities in attitudes, values, thought processes, behaviors, personal preferences and even communication practices.

Generational characteristics are particularly noticeable when a cohort is compared to older or younger generations. Each generation has particular ways of acting, particular mental models that guide decision-making and particular preferences that differ from those of other generations.2

Today's workforce is made up of three such generations.

Baby boomers are the approximately 80 million people born in the U.S. during the post-World War II years, roughly 1945 to 1964, a time of prosperity. During the 1950s and 1960s, the national mindset was one of ambition and accomplishment — "I can do whatever I set out to do" — perhaps best exemplified by the United States landing men on the moon and bringing them home safely.

Social changes shaped baby boomers in ways that often dismayed their parents. It was a generation that questioned authority, distrusted the government, protested the Vietnam War, and participated in the civil rights and women's equal rights movements. Many baby boomers hoped to change the world and make it a more peaceful place through music, drugs, the sexual revolution and communal life.

The assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., roiled American society, as did the U.S. Senate's "Watergate" hearings that led President Richard M. Nixon to resign rather than be impeached for covering up illegal activities during his 1972 re-election campaign.

The boomer generation is a large one, so its members learned to compete for the things they wanted. This attitude carried over as they entered the workplace and committed long hours and personal sacrifice to their careers, earning them the label "workaholic." While often accused of being self-absorbed, baby boomers maintained their parents' value of loyalty to their employers, an attitude eventually shaken by the business downsizings, mergers and layoffs of the past few decades.3

Generation Xers, born between approximately 1965 and 1980, are a group of about 44 million. They are sandwiched between two generations that vastly outnumber them. Generation Xers grew up witnessing parents being laid off, divorce rates climbing and economic pressures that resulted in Xers becoming the first "latchkey" generation needing to fend for themselves after school until a parent came home from work. With such factors influencing their generational personality, Xers grew up self-reliant, autonomous and possessing a low trust of organizations. They are characterized as impatient individuals who value versatility in their careers and the opportunity to gain experiences and manage opportunities. They are very comfortable with diversity, change and multitasking, but loyalty to the employer's organization is not an Xer priority.4

Our youngest workplace generation is the millennials, also referred to as Generation Y, trophy kids or the Nexter group. Millennials are individuals born between about 1981 and 2005 and, like the baby boomers, they are a large population — approximately 70 million. Millennials began entering the workplace about 12 years ago, and the oldest of the cohort are now in their 30s. As boomers retire and leave the workplace, there aren't enough Generation Xers to replace them, thus millennials are likely to have career promotion opportunities much earlier than has been the case for other groups.5

A hallmark of the millennial generation is that technology is who they are, not what they use as a tool. Smart phones in hand, they have grown up surrounded by technology ranging from microwaves to the Internet and are accustomed to immediate results and instant contact. It should not be surprising that they are known for their impatience.

They also are known as a protected generation — millennials were the "baby on board" and the kids who received trophies for just being on a team. The term "helicopter parents" was coined to describe moms and dads hovering over their millennial children to provide protection. The adage "children should be seen and not heard" didn't apply to the millennials, confident from an early age that voicing their opinions was welcome and important.

In school, cooperation and collaborating on team projects were the norm, and millennials have carried this collective orientation into their workplaces. Keeping in constant communication with their friends is important to them, and unlike the workaholic boomers, millennials demand a balance between work and personal life. Their generational personality is optimistic, confident, and highly social.6

NURSES BY THE NUMBERS

Examined through a generational lens, the current nurse workforce of 3.1 million is approximately 44.7 percent, or 1.4 million, baby boomers; 37.4 percent, or 1.1 million, Generation Xers; and 17.9 percent, or 550,000, millennials. Not quite two-thirds of these nurses are employed in hospitals.7

Because the largest population cohort is made up of baby boomers, it should be no surprise that the mean age for nurses is 50 years old. Fifty-three percent of nurses over age 50 are still working.8

As boomers retire, changing numbers bring new concerns. First, the retirements may create something of a brain drain in the delivery of services because the most experienced, knowledgeable nurses are leaving.9

Second, while millennial nurses are expected to be the primary answer to addressing nursing shortages, statistics show millennial nurses are leaving their hospital positions and even the profession in record numbers.10 Some leave out of frustration because they feel they are having to respond to situations for which they are unprepared, and increased workloads cut into the time new nurses need to develop their competencies. Other millennials will leave a job to achieve a better work schedule or flexible hours, and to the millennial generation, job-hopping is an acceptable method of career advancement.11

Third, in addition to nurse vacancies caused by boomer retirements and current shortages, the U.S. population is aging and many new nurse positions will be required to address an increasing demand for health care services.12

As a result, the future could hold such a significant number of unfilled nursing positions that organizations will be fighting for — and over — applicants.

In summary, we need:

- Hundreds of thousands of new nurses to join the workforce in order to meet the projected expanded demand.13

- RN retention measures to slow boomer retirements and millennial job-hopping.

- Effective collaborative relationships between multigenerational nurses in the workforce that reduce tensions on the job and support the provision of quality nursing services.

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

With job "leakage" at both ends of the age spectrum (i.e., baby boomers retiring and millennials leaving), it is important to identify generational intervention strategies at all levels. Many articles approach this from an organizational perspective. They typically identify a variety of organizational tactics focused on human resources issues such as recruiting, hiring and orientation.14

Less common are articles that approach the generational issues from an intrapersonal and interpersonal perspective. In working with these issues over the past 10 years, it is our experience that discussions of generational differences are accompanied by strong emotions ("I can't believe she said that!" "I can't believe he acts like that!")

Initially a common organizational response to employee relations tensions associated with the arrival of the millennials was to downplay them. "What's all the fuss? They are young. They'll learn that they have to change if they want to be successful."

Generational theorists predicted that these generational-based tensions would not solve themselves, and organizations are now agreeing as they adopt various generational interventions.

In order to reduce tensions on the job, we have found nurses must learn to recognize and manage their own emotions springing from generational issues and to respond appropriately to the emotions of others.

According to Daniel Goleman, emotional intelligence is "the ability to manage ourselves and our relationships effectively."15 It encompasses four fundamental capabilities: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness and social skill. While all four of these capabilities are needed in addressing generational issues, in our experience, failures in employee relations are often due to a lack of appreciation of the latter two: social awareness (i.e. empathy) and social skill.

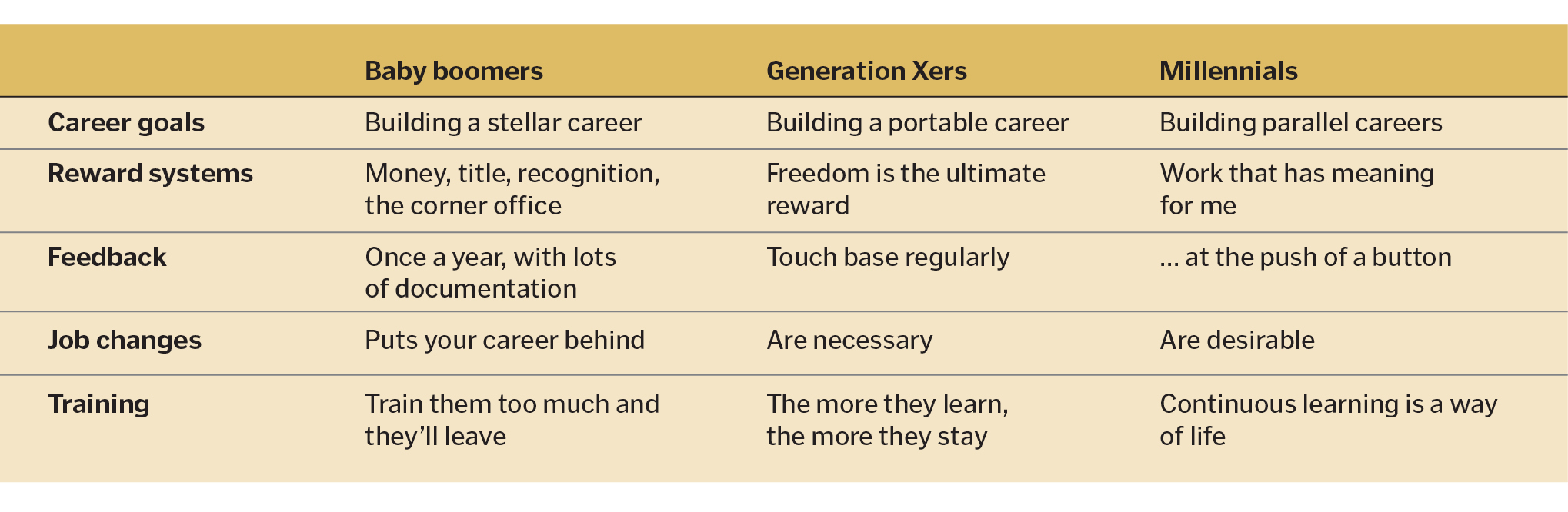

The following table illustrates several different generational perspectives related to work that require social awareness and social skill competencies:

Generational differences clearly have made manager-employee and peer-peer relations considerably more complex. Although the Golden Rule is a standard guideline for handling relationships, generational differences mean it may be more effective to treat others the way they want to be treated.16

As nurses develop their emotional intelligence concerning generational issues, they should find themselves more accepting of different generational perspectives and more effective in addressing interpersonal relations. If they are successful — and assuming better emotional intelligence results in better job satisfaction — nurses are less likely to leave their organizations and more likely to achieve improved team collaboration.

TACTICS

A combination of tactics can help nurses improve their generational emotional intelligence. Training about generational diversity is the most common approach. Some organizations provide training to all employees, usually in mixed generational groups. Others provide newly hired millennials with a specialized program to help them acclimate to the work environment. Still others manage the exceptions: They identify employees who are problematic and work with them individually through coaching or corrective actions.

Diversity training typically addresses the notion that we're different, but the same. Generational interventions that simply teach about differences can backfire because the approach is one-sided. It neglects to provide the counterbalance of recognizing and appreciating things the work group has in common. We recommend, for example, that nurses identify and accent the things that all nurses have in common. Once identified, these attitudes and attributes represent the group's shared nursing identity and provide a strong foundation for accepting and even valuing differences.

A facilitated group process is the best way to generate, appreciate and own common connections. To get the group started, some common nursing connections include:

- A personal mission to care for the patient/every patient

- Commitment to continual learning

- Team orientation

MANAGERS AND RETENTION

Researchers have studied a number of variables regarding the intent to continue working in nursing. One of the more significant findings is that when high quality relationships exist between nurses and their supervisors, nurses report a stronger intention to stay.17

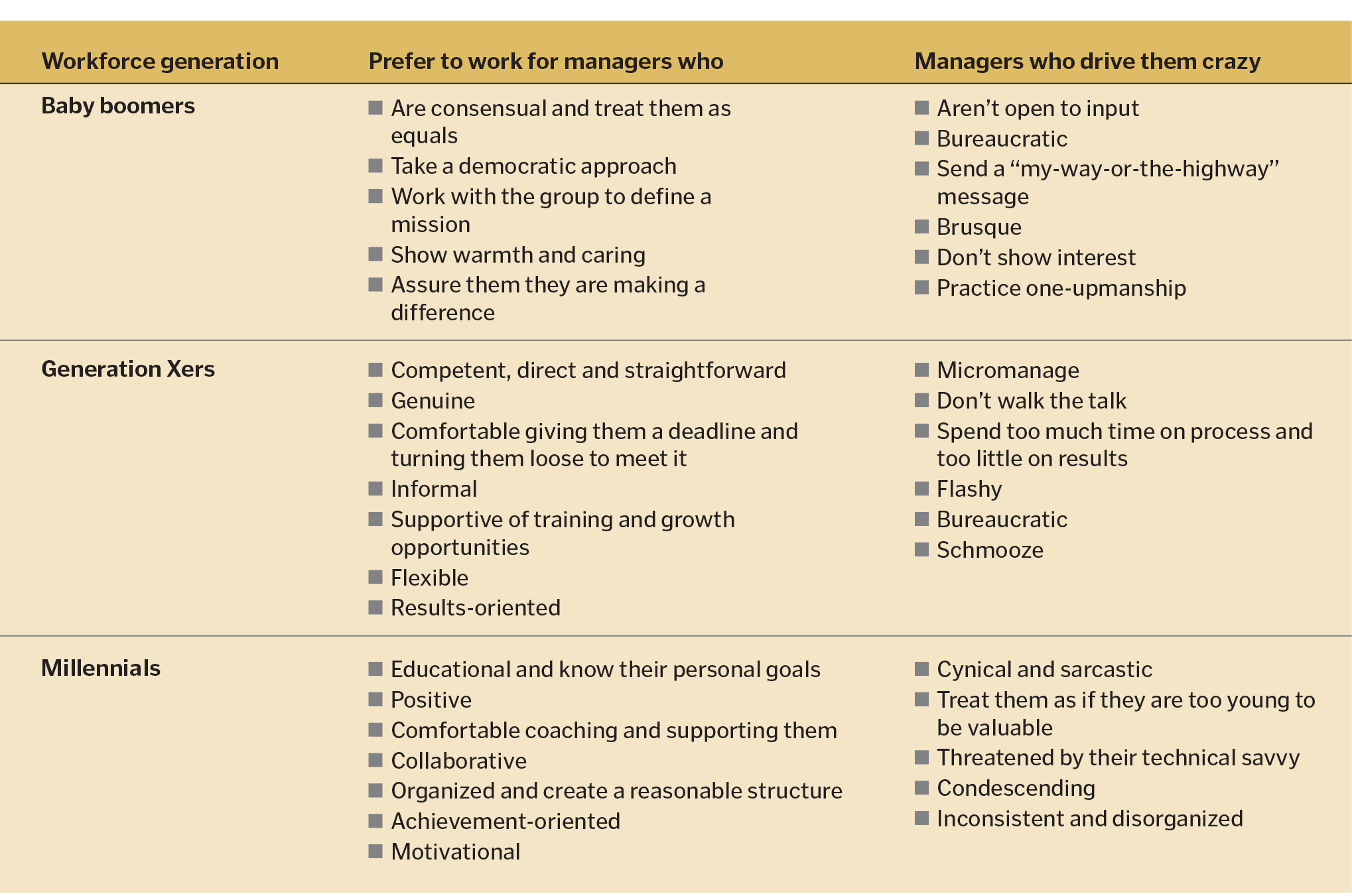

The chart above illustrates how different generations view managers. Although all of the behaviors in the right column are negative and should be discouraged, the variety of positive behaviors in the left column, organized according to generational preferences, means that the job of the nursing manager has become more complex. Because most nurse managers will have multi-generational employees, a one-size-fits-all approach won't be effective. Therefore, nursing leaders should exercise contextual leadership, that is, adjust their leadership responses to fit their followers' needs and preferences.

Together, these three personal strategies for addressing generational issues — emotional intelligence, shared identity and leader generational response — should mitigate generational issues in nursing units, thereby lessening their influence on RN turnover and collaborative tensions. As an interpersonal approach to generational problem solving, they reflect Mahatma Gandhi's guidance, "You must be the change you wish to see in the world."

TERRENCE F. CAHILL, is chair/associate professor, Department of Interprofessional Health Sciences and Health Administration, Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey.

LAURA E. CIMA is assistant professor, Felician University, Lodi, New Jersey.

NOTES

- Elizabeth J. Currie and Roy A. Carr Hill, "What Are the Reasons for High Turnover in Nursing? A Discussion of Presumed Causal Factors and Remedies," International Journal of Nursing Studies 49, no. 9 (September 2012): 1180-89.

- Ann E. Tourangeau et al., "Generation-Specific Incentives and Disincentives for Nurses to Remain Employed in Acute Care Hospitals," Journal of Nursing Management 21, no. 3 (May 15, 2012): 473-82.

- Angela C. Wolfe et al., "Beyond Generational Differences: A Literature Review of the Impact of Relational Diversity on Nurses' Attitude and Work," Journal of Nursing Management 18, no. 8 (November 2010): 948-69.

- Angela C. Wolfe et al., "Beyond Generational Differences."

- Angela C. Wolfe et al., "Beyond Generational Differences."

- Angela C. Wolfe et al., "Beyond Generational Differences."

- American Nurses Association, Fact sheet: Registered Nurses in the U.S., Nursing by the Numbers. http://nursingworld.org/Content/NNW-Archive/NationalNursesWeek/MediaKit/NursingbytheNumbers.pdf.

- American Nurses Association, "Fast Facts: 2014 Nursing Workforce: Growth, Salaries, Education, Demographics & Trends," www.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ThePracticeofProfessionalNursing/workforce/Fast-Facts-2014-Nursing-Workforce.pdf.

- Laura A. Stokowski, "Nurses Are Talking about the Real Reasons They Postpone Retirement," Medscape Multispecialty (May 7, 2015). www.medscape.com/viewarticle/843597.

- Melanie Lavoie-Tremblay et al., "The Needs and Expectations of Generation Y Nurses in the Workplace," Journal for Nurses in Staff Development 26, no. 1 (January-February 2010): 2-8.

- Melanie Lavoie-Tremblay et al., "The Needs and Expectations of Generation Y Nurses in the Workplace."

- American Nurses Association, "Fast Facts: 2014 Nursing Workforce."

- American Nurses Association, "Fast Facts: 2014 Nursing Workforce."

- Terrence F. Cahill and Mona Sedrak, "Age-Related

Conflicts: The Generational Divide," Health Progress 92, no. 4 (July-August, 2011): 31-35. - Daniel Goleman, "Leadership That Gets Results," Harvard Business Review, (March-April 2000).

- Tony Alessandra and Michael J. O'Connor, The Platinum Rule: Discover the Four Basic Business Personalities and How They Can Lead You to Success (New York: Hachette Book Group, 1998).

- Ann E. Tourangeau et al., "Determinants of Hospital Nurse Intention to Remain Employed; Broadening our Understanding," Journal of Advanced Nursing 66, no. 1 (January 2010): 22-32.