BY: LAWRENCE PRYBIL, Ph.D., LFACHE, and REX KILLIAN, J.D.

Nonprofit hospitals and health systems historically received tax-exempt status based on the premise that a principal reason for their existence was providing charity care to persons who needed health care services but were unable to pay for them. In 1965, Congress enacted Public Law 89-97 which established the Medicare and Medicaid programs and significantly expanded health insurance coverage for elderly and poor Americans.

In 1969, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) issued Revenue Ruling 69-545 which shifted the basic rationale for granting tax-exempt status to nonprofit health care institutions from providing charity care to providing "community benefit."1 In the ruling, the IRS reasoned that providing health care services for the general benefit of the community inherently is a charitable purpose. The ruling listed the factors that would be considered in granting tax-exempt status, and, in doing so, created the co-called community benefit standard.2

As time passed and society experienced major economic, demographic and political changes, many in both the public and private sectors began to raise questions about the adequacy of the community benefit standard as the basis for awarding tax-exempt status to nonprofit health care institutions. Studies conducted by the IRS, the General Accounting Office and other organizations showed wide variability in the definitions and amounts of "uncompensated care" and other forms of community benefit provided by nonprofit health care institutions.3

These issues have contributed to the adoption of various forms of community benefit requirements (such as a specific level of charity care and/or standard reporting rules) for nonprofit health care institutions in about half of the states.4 At the federal level, continuing concerns about the utility of the IRS community benefit standard, the absence of agreed-upon community benefit definitions and wide variation in the amounts of uncompensated care provided by nonprofit hospitals and systems led, in 2007, to substantial revisions in the IRS Form 990, "Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax." The redesigned form consists of a common document that must be completed by tax-exempt organizations and a series of schedules that organizations may need to complete depending upon their particular roles and activities. Phased in during 2008, this was the first major revision to Form 990 since 1979.

According to the IRS, Schedule H was intended to "… combat the lack of transparency surrounding the activities of tax-exempt organizations that provide hospital or medical care."5For nonprofit health care institutions, the revised Form 990 and Schedule H required much more extensive information about charity care (referred to in Schedule H as "financial assistance") and other aspects of community benefit than in the past.

Since its adoption in 2007, Form 990 and the related schedules were refined somewhat but remained basically intact. However, the Patient Protection and Accountable Care Act (ACA) adopted in 2010 amended the IRS code by adding Section 501(r)(3). It requires every hospital facility operated by a tax-exempt organization to conduct a community health needs assessment with input from interested parties in the community at least once every three years and develop implementation strategies to address community needs identified through that process. In April 2013, the IRS issued proposed regulations that, when finalized and implemented, will provide further guidance on requirements for community needs assessment. In addition, Section 9007 of the ACA requires the Secretary of the Treasury to make annual reports to Congress on four categories of community benefit incurred by tax-exempt hospitals: charity care, bad debt, unreimbursed costs for services of government programs and the costs of community benefit activities.

These developments are creating more uniformity in reporting and increasing the visibility of information regarding community benefit activities. Public and private organizations with oversight responsibility for nonprofit hospitals and health systems are scrutinizing their performance more closely than ever and are expecting more accountability by the persons who govern and manage them. For the boards of nonprofit hospitals and systems, providing direction for their organization's community benefit policies and programs and monitoring the results now are regarded as a fundamental governance responsibility.6

STUDY OF GOVERNANCE IN LARGE NONPROFIT HEALTH SYSTEMS

A recently completed study examined board structures, processes and cultures in large nonprofit health systems and compared them to contemporary benchmarks of effective governance. Information was gathered by reviewing system documents, on-site interviews with the systems' CEOs and senior board leaders and discussions with system staff.7 Fourteen of the country's 15 largest systems participated in this study; eight of these 14 systems are sponsored or controlled by Roman Catholic entities.8 The scope of this study included reviewing several aspects of the boards' involvement in directing and monitoring the systems' community benefit activities.

FINDINGS

Board committee oversight: A well-organized committee structure with clearly defined duties and knowledgeable, engaged members is a key to effective governance.9 In this context, assigning oversight responsibility for specific governance functions to standing board committees is widely accepted as a sound governance practice.

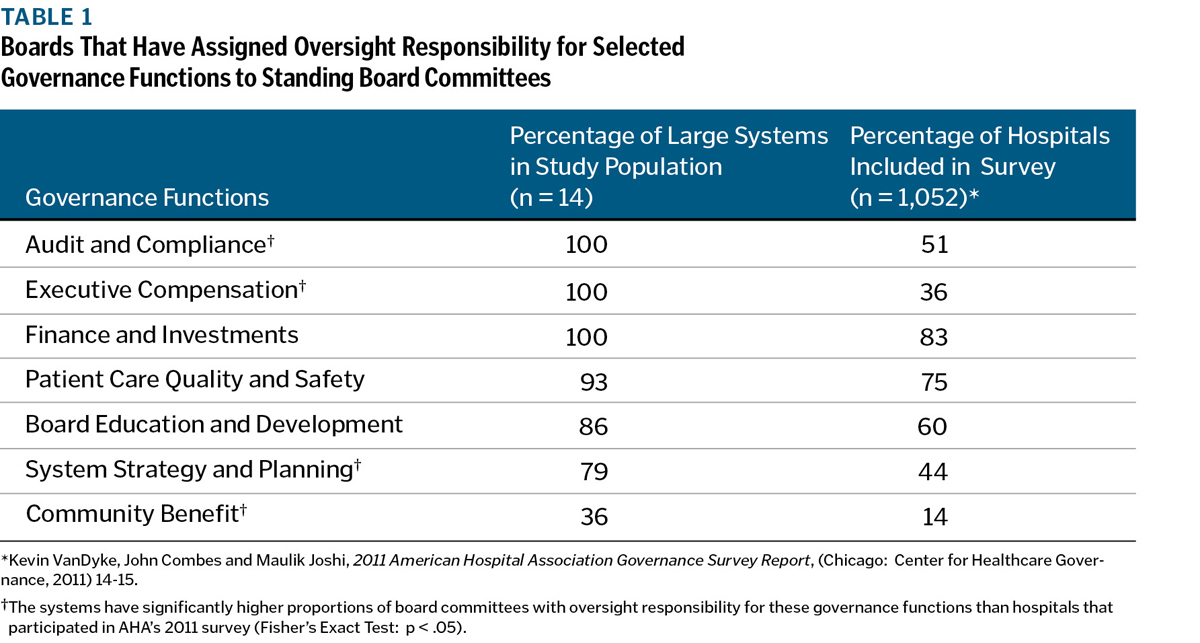

Based on interviews with board members and CEOs and information obtained from system documents, Table 1 shows the number and proportion of boards in this study population that assigned oversight responsibility for seven core governance functions to standing board committees. It also provides comparable information from the American Hospital Association's (AHA) 2011 national survey of hospitals and systems.

Across the board, large health systems are more likely than hospitals to have standing committees with oversight responsibility for these important functions. For several functions, this practice is virtually universal among these large systems. However, at the time of the site visits, only five of the 14 systems (three Catholic systems and two secular systems) had standing board committees with oversight responsibility for system-wide community benefit policies and programs. Some systems were contemplating taking that step, and at least one already has done so.

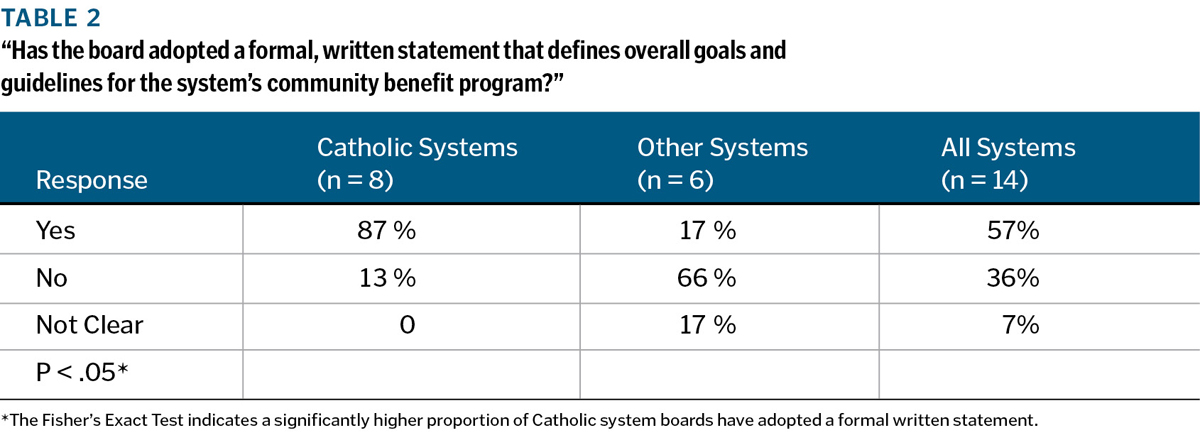

Adoption of formal goals and guidelines for community benefit programs: The interviews with board leaders and CEOs included several questions regarding their particular system's community benefit policies and programs. The first was "Has your board adopted a formal, written statement that defines overall goals and guidelines for your system's community benefit program?"Table 2 compares the findings for Catholic systems to the other large systems. It shows that, when the site visits were conducted in FY 2011 and FY 2012, 87 percent of the Catholic systems' boards (seven of eight) had adopted a formal policy as compared to only 17 percent of the other systems.

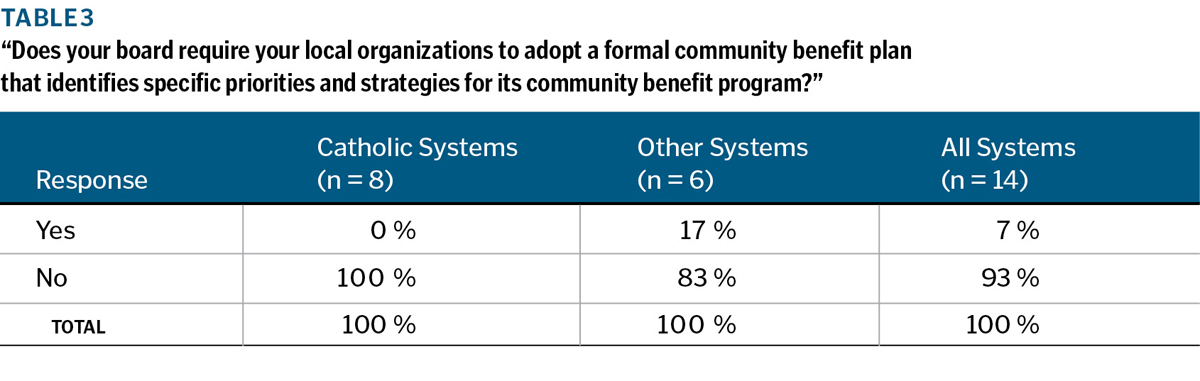

Collaboration with local public health organizations: As one way to gauge the participating systems' current position on coordination between their local delivery organizations and public health agencies, the board members and CEOs were asked if their system's board requires (not just "encourages") their local organization to collaborate with local public health organizations in their vicinities. The information presented in Table 3 shows that, when site visits were conducted during FY 2011 and FY 2012, such requirements were quite uncommon. Only one of the 14 large systems, a secular organization, had established a policy requiring all of its local organizations to collaborate with local public health organizations in assessing community needs and setting community benefit program priorities.

However, in recognition of the nationwide need for greater focus on prevention and population health, many board members and CEOs — both in Catholic and secular systems — expressed support for the idea of promoting stronger communication and coordination between their local leadership teams and public health organizations. The ACA's provisions as well as the National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care promulgated by the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2011 are expected to promote more collaboration with public health organizations in the future.

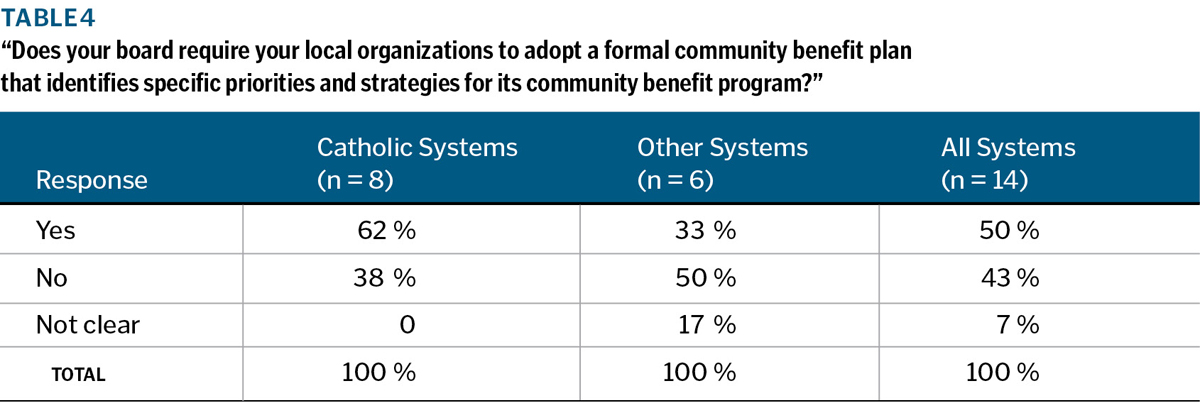

Adoption of formal community benefit plans by the systems' local organizations: In the current environment and the foreseeable future, public and private organizations in virtually all sectors of American society face serious financial constraints and must establish resource allocation priorities very carefully. For America's hospitals as a whole, uncompensated care (charity care and bad debt) increased from $21.6 billion in 2000 to $39.3 billion in 2010, an increase of 82 percent. This trend clearly has affected the availability of resources for other categories of community benefit activities.10 For this and other reasons, developing formal plans and setting clear priorities for community benefit programs has emerged as a basic indicator of effective governance and management in health care organizations.11

In the interview process, CEOs and board leaders were asked if, in their opinion, their system's board has required their local organizations to develop and adopt a formal community benefit plan that identifies specific priorities for its community benefit program. Their views were verified by reviewing system documents. As shown in Table 4, 50 percent of these large systems — including five of the eight Catholic systems — have directed their local leadership teams to develop formal plans with priorities, strategies and metrics for their community benefit programs. In several instances, they specify that local plans must address certain system-wide priorities. As the provisions of IRS Code Section 501(r)(3) are implemented and resources become further constrained, ongoing assessment of community health needs, careful prioritization of those needs, and adoption of formal community benefit plans at both the local and system levels of nonprofit health systems are likely to become increasingly prevalent.

Societal realities are demanding fundamental change in the mission and goals of public and private health organizations and the services they provide to their communities. Stakeholders want assurance that nonprofit hospitals and health systems deserve tax-exempt status and are meeting high-priority community needs and that public health organizations are performing their vital functions efficiently. Concurrently, the historic roles of hospitals, health systems and public health organizations are evolving as all parties recognize that prevention of illness and injuries, early detection and treatment and intentional promotion of wellness in all sectors of the population are imperative. Better communication and closer collaboration among health systems and public health organizations in improving the health status of communities they jointly serve is essential.

Therefore, the team that conducted this study recommends that the board leaders and CEOs of nonprofit health systems, accountable care organizations and hospitals, if they have not already done so, charge a standing board committee with oversight responsibility for their organization's community benefit policies and programs and its role and priorities in the realm of population health. It is time for a fresh look at traditional practices and relationships — and for new approaches that will serve our communities better and more efficiently.12

LAWRENCE PRYBIL is the Norton Professor in Healthcare Leadership, College of Public Health, University of Kentucky, Lexington. REX KILLIAN is of counsel, Hall, Render, Killian, Heath & Lyman in Indianapolis.

NOTES

- Much of the data and text presented in this article is excerpted from Lawrence Prybil et al., Governance in Large Nonprofit Health Systems: Current Profile and Emerging Patterns (Lexington, Ky.: Commonwealth

Center for Governance Studies, 2012), www.americangovernance.com/gov-booklet. - In Revenue Ruling 69-545, 1969-2, C.B. 117, the factors that comprised the community benefit standard included: maintaining an emergency room on a 24-hour-per-day basis; providing charity care to the extent of the institutional financial abilities; granting medical staff privileges to all qualified physicians in the community consistent with the size and nature of the institution; accepting payment from the Medicare and Medicaid programs on a nondiscriminatory basis; and maintaining a community-controlled board composed primarily of persons from the local community and not controlled by insiders. A later IRS ruling (Rev. Rul, 83-157. 1983-2 C.B. 94) stated that a hospital did not need to maintain and operate an emergency room to qualify for tax exemption if it showed that adequate emergency services existed elsewhere in the community and the hospital met the other requirements of the community benefit standard.

- See, for example, David M. Walker, Comptroller General of the United States, testimony to the House Committee on Ways and Means on May 26, 2005, "Nonprofit, For-Profit, and Governmental Hospitals: Uncompensated Care and Other Community Benefit."

- See, for example, Fred Hellinger, "Tax-Exempt Hospitals and Community Benefits: A Review of State Reporting Requirements," Journal of Health Policy, Politics, and Law 34, no. 1 (February, 2009): 37-61.

- Donna C. Folkemer et al., "Hospital Community Benefits After the ACA: The Emerging Federal Framework," The Hilltop Institute: Issue Brief, January 2011.

- See, for example, The IRS Form 990, Schedule H:

Community Benefit and Catholic Health Care Governance Leaders (St. Louis: Catholic Health Association of the United States, 2009); and Gerard Magill and Lawrence D. Prybil, "Board Oversight of Community Benefit: An Ethical Imperative," Kennedy Institute of

Ethics Journal 21, no. 1 (March, 2011): 25-50. - See Prybil et al., Governance 3-9.

- The 14 systems that participated are: Adventist Health System Sunbelt Health Care Corp., Altamonte Springs, Fla.; Ascension Health, St. Louis; Banner Health, Phoenix; Carolinas Healthcare System, Charlotte, N.C.; Catholic Health East, Newtown Square, Pa.; Catholic Health Initiatives, Englewood, Colo.; Catholic Health Partners, Cincinnati; CHRISTUS Health, Irving, Texas; Kaiser Foundation Hospitals and Health Plan, Oakland, Calif.; Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.; Mercy, Chesterfield, Mo.; Providence Health & Services, Renton, Wash.; Sutter Health, Sacramento, Calif.; and Trinity Health, Novi, Mich.

- Larry L. Walker, "The Supporting Cast:Strong, Focused Committees and Task Forces Are Essential to Overall Governance Excellence," Trustee 65, no. 3: 6-7.

- "AHA:Hospitals' Uncompensated Care Increased 82 Percent Since 2000," AHA News, Jan. 9, 2012. The figures for uncompensated care in 2000 and 2010 include charity and bad debt; they do not include Medicaid or Medicare underpayment costs.

- See, for example, Lawrence Prybil and Janet Benton, "Community Benefit: The Nonprofit Community Health System Perspective," in Governance for Health Care Providers: The Call to Leadership, ed. David B. Nash et al. (Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press, 2009), 267-283; and Connie Evashwick and Kanak Gautam, "Governance and Management of Community Benefit," Health Progress 89,

no. 5 (Sept.-Oct. 2008) 10. - See Prybil et al., Governance, 56.