Summary

In a future that will involve new accountabilities, greater risks, and more adaptability, board members must learn to function well at three levels:

- They must retain the grand vision of what their organization can be.

- Their strategies must be effective enough to enable them to win more battles than they lose.

- They must oversee without meddling, approve without operating, and steward their resources with care and compassion for their institution's employees and patients.

The financial pressures that exist at every level of our operations can make it difficult for board members to keep focused on their institution's mission. Board members must also grapple with increased government intervention, blurred institutional boundaries, more powerful insurers, and conflicts between institutions and physicians.

To perform well in such an environment, board members must focus on their unique role in institutional governance. In addition, they must understand the organization's mission, be aware of the changes brought about by new financial incentives for providers, learn to work well with diverse institutions, and understand the concerns of physicians in a changing healthcare scene. Trustees must also be aware that changing goals and incentives will require healthcare providers to adopt a new, prevention-oriented approach to healthcare delivery.

New, postreform healthcare structures will require new kinds of leaders at the board level, with broader backgrounds and special skills. What kind of response could we anticipate to this kind of ad?

Trustee Candidates

Background

In-depth management and/or governance experience in medium-to-large, diversified healthcare institution. Also, in-depth management experience in medium-to-large corporate or not-for-profit organization, including finance, strategic planning, new product development, merger/acquisition, marketing, and research.Availability

Ten to twenty percent FTE. At times, may reach almost 100 percent.Special Skills

- Ability to deal effectively with competing interests, including competing factions within integrated delivery networks.

- Ability to juggle complex financial incentive systems and multiple accountability processes.

- Vision to understand shared cultures and to perceive ways to achieve most effective synergies among combined values. Affinity for creating new systems and policies for unprecedented joint ventures.

- Experience in resource consolidation within new ventures and ability to outplace duplicated resources and people.

Compensation

Low.Other benefits

To be determined.

The coming changes in healthcare structures, financing, and delivery systems will transform Catholic institutions from their roots to the highest levels of governance. The high-speed metamorphosis will strain their ability to recruit, educate, and keep effective trustees, both lay and religious.

In my firm's approach to the management of Catholic healthcare institutions, we concentrate on the unique structure and processes according to which a sponsoring group, a legal board, and medical staff leaders share power. We believe that how institutions address governance issues will be key to their ability to change and survive in a new game with new rules. In spite of the magnitude of the coming changes, we can achieve continuing, effective stewardship of our present organizations with careful planning, realistic expectations, and a strategic program of trustee orientation and involvement.

To thrive in the new environment, Catholic healthcare institutions will require the guidance of trustees who function well at three levels:

- First, they must retain the grand vision of what their organization can be.

- Second, their strategies must be effective enough to enable them to win more battles than they lose.

- Third, they must oversee without meddling, approve without operating, and steward their resources with care and compassion for their institution's employees and patients.

One View of the Future

What will the typical, successful Catholic institution board of trustees of tomorrow look like? And how will it work?

New Accountabilities

Boards will become more aggressive as healthcare comes to more closely resemble other giant industries. New demands for increased efficiency, leanness, competition, and dollars from downsized operations will challenge traditional concern for mission and community service. The number of "authorities" to which boards are accountable will increase. More decisions will be made by financial rather than medical people, requiring increasingly diligent oversight. Boards may feel pressure to change from being care takers or stewards of existing resources to assisting in the competitive development of new resources.

A new kind of visionary trustee will be required to successfully juggle the best of the mission-community service orientation long characteristic of Catholic institutional boards with today's financial and regulatory responsibilities.

More Risk

The board will have to take more risks. Healthcare providers are moving into uncharted territory, with few good models to follow. In addition, most consumers will probably dislike the changes they encounter in the new healthcare system. They will be watching closely and will be ready to find healthcare organizations at fault. Providers will face enormous financial, liability, and public relations obstacles. Few physicians will be willing to take more than minimal risks with them.

Shared Control

Boards will have to learn to share control of their institutions and their networks. This will be difficult for both lay and religious trustees. Both can be expected to be protective of their institution's autonomy, power base, and mission. More flexible attitudes, willingness to compromise, and concern for financial viability will be required.

Smaller Boards

Because of all these conditions, boards may be smaller in the future. Many members may decide that service in these new, complex institutions — many of them very different from the traditional Catholic hospital or system — no longer merits the same commitment they have made in the past. However, other members may be attracted by the challenge of pursuing traditional missions under new structures.

Better Compensation

Finally, Catholic institutions may have to pay for the level of board leadership and production that they require. It seems incongruous to expect trustees, lay or religious, to take on more demanding tasks and higher risks without reward beyond the pleasure of serving. Perhaps even more than in the corporate world, where directors are often well compensated for relatively little time and effort, the special demands of healthcare reform may require a higher level of tangible compensation for a difficult job well done.

Complex Challenges

The problems confronting most Catholic healthcare institutions can be ticked off quickly by even the newest trustees. Financial pressures exist at every level of operations and throughout capital programs. The causes are well known; the solutions, not in sight.

Trustees know that Catholic healthcare institutions, like almost all others in society, have grown much more complex. Driven partly by developments in medical and communication technology, partly by increased size, and very much by financial pressures and government programs designed to alleviate these pressures, these institutions struggle to cope. Too often, their responses are not as well-reasoned and strategically planned as they might be.

As society changes and competition increases, Catholic healthcare missions may lose their clarity, especially in the eyes of trustees. We may be tempted to modify our objectives to meet the marketing opportunity of the moment. Some days, our mission may seem naive or hopelessly out of date.

In our enthusiasm for collaboration, we establish close relationships with vastly different organizations, including non-Catholic institutions. Can we continue to pursue our mission in this changed environment? Do trustees truly understand and support what the institution is trying to do?

Effect of Reform

Against this backdrop, boards must also prepare themselves for the changes that healthcare reform will introduce. Of course, the Clinton plan, and any others, will be subject to months or even years of congressional modifications before the proposed reform becomes a reality. What do these plot twists hold for trustees? A number of changes will become evident over the coming months.

Increased Government Intervention

Additional government interventions will further limit institutional flexibility. Healthcare institutions are accustomed to dealing with government intervention in the area of reimbursement. Now, government controls will have an impact on revenues and expenditures and virtually all activities.

Government will use fiscal policy more aggressively than ever to change the delivery system. But now, with capitation, providers will be rewarded as much for what they do not do as for what they do. Financial incentives will favor prevention over intervention. Succeeding now becomes a market share game won in the utilization trenches, and the battle between "protecting the mission" versus "increasing the revenue stream" goes on.

Blurred Institutional Identities

Institutional identities will become blurred. My firm is currently working with two Southeast hospitals, one Catholic and the other a community not-for-profit. Clearly future delivery systems will not support both. Both boards realize this and are working through initial affiliation talks. One question driving their negotiations is, What is our role in the community? Identifying and embracing a new role will be difficult for both providers because neither likes the idea of giving up service, power, location, or revenue.

More Powerful Insurers

Insurance companies will take on new powers, dominating some markets in unprecedented ways. In one situation in the Midwest, a large, successful group practice is being sought by a hospital and several insurance companies. The insurance companies, which have no trouble providing incentives to physicians because physicians are their means to profits, have no interest in capitating any hospital. Neither community service nor mission is a factor.

If the insurance companies prevail, the hospital could be reduced to a vendor selling services at the lowest prevailing prices. The moral: Hospitals must participate as power players in the development of integrated delivery networks (IDNs), or they may lose both their mission and the revenue to pursue it.

Institution-Physician Conflicts

Institution-physician conflicts may increase significantly. Trustees will find themselves in the middle.

Conflicts, often the result of power-brokering, will escalate. Many hospital managers are reluctant to share power with physicians. Yet, physicians, who will be critical to the success of any delivery system, will not come along without input into the decision-making process.

Improving Trustee Performance

Boards of trustees will be better prepared to meet the challenges posed by new types of institutions if steps are taken to improve performance now, in current institutional settings. Sponsoring groups and hospital administrators can initiate some of these changes. The board itself must initiate others.

Play the Proper Role

The board can do much to improve its own performance and to ready itself for greater challenges. Boards should, first of all, ensure that they focus on their proper roles. Trustees often spend their time and energy on the wrong topics — typically operational instead of strategic matters.

Sometimes boards concentrate on the wrong issues because they want to. It is easier and safer to study the past than the future and to focus on operations rather than planning. But the board's proper role, which is unique in governance structures, is to focus on broad policy issues and strategic plans for the future.

Understand New Financial Incentives

The board must also learn to deal with new kinds of financial incentives. The economics of healthcare have been changing radically since 1983. Obviously, the days of opening the doors to patients who enter and gratefully pay for their treatment are long gone.

But many boards remain unaccustomed to an aggressive pursuit of the patients and the payers who meet their mission criteria and can fund their basic operations, including charity care. The new challenge is to reconcile concerns over market share and finance with commitment to values and mission. A vastly more complex environment, driven largely by external forces, renders this task even more difficult.

In a reformed healthcare system, the ability to channel patients to particular providers will be the key to success. By using marketing techniques and financial incentives to influence how and where people are treated, providers can gain market share while ensuring that patients receive appropriate care in the appropriate setting.

Trustees must come to understand that hospitals and physicians are "downstream" in the flow of reimbursement dollars. In a reformed system with heavy reliance on managed care, downstream is not the best place to be, for providers can quickly become nothing more than vendors. The preferred strategic direction is "upstream," closer to the reimbursement dollar, closer to the premiums being paid. Primary care physicians are already further upstream than hospitals and specialists, and competition for a position upstream will be intense with the insurance companies holding the highest ground.

Welcome Diversity

Board members must also learn to welcome the diverse kinds of institutions that will join forces in IDNs. Becoming limited partners with a hospital across town is one thing; joining up with an insurance company or a physician group is quite another. But the successful boards and institutions will use the current transitional time to teach board members about these new relationships and to recruit others who will be up to the task ahead.

Understand Physicians' Plight

Finally, board members must make an effort to understand the position of physicians, who are encountering career-shattering pressures and uncertainties. Perhaps more than any other profession, physicians have enjoyed a secure and comfortable world. Suddenly, many of the basic values and life-style choices that originally attracted them to medicine seem to be on an auction block, for sale to the highest bidder, but without rewards accruing to themselves. Boards need open and honest communication with their physicians and patience with their struggles.

This may not be easy, however. In one conflict in California, a strong group of primary physicians is intent on breaking their specialist colleagues. The primaries control an independent practice association that has several health maintenance organization contracts. Their first move against the specialists was to kick them out of risk pool participation. Next, they reduced specialists' fees under threat of sending business out of town. Finally, the primary care physicians caused specialists' referrals to plummet as they began to do more work, formerly referred, in their own offices.

The key lesson for all involved is that whoever holds the contract controls the flow of patients and dollars. From a purely economic perspective, the primaries' moves were predictable. But what happened to ethics and to concern for patient welfare?

In this situation, ample evidence exists that referrals are being made on the basis of dollars rather than quality of care or outcome. Patients will get hurt if this brand of checkbook medicine gains prominence.

Understanding the Organization

Trustees may understand the financial and operational foundations of the institution or system. But do they have adequate knowledge of the sponsor's desires, of the patients' needs, of physicians' responsibilities, of the payers' restrictions, and of the network or system's intertwined missions?

Mission

For a trustee to function effectively, he or she must understand the institution's mission, which must be expressed in a simple, written, up-to-date document. The mission statement must point the way into the future, providing a dynamic summary of what and why the institution is and is becoming (see "Mission Statement: Key Questions" at the end of this article). Many trustees are familiar with corporate positioning statements. The mission statement must drive the hospital in the same sense a positioning statement drives a corporation's growth and development.

Current Status

Beyond understanding where the institution or system or network is going, the trustee needs to know where it is now. What is the institution's position in the marketplace measured in hard data such as market share by modality figures, income and expenses, overlapping programs, admissions, length of stay, dollars of charity care offered? To be meaningful, the figures must have comparative bases, with preceding years, competing hospitals, other hospitals of the same type, and future projections.

Yet even trustees with clear and well-documented understanding of how their institution functions may have to learn to invert their thinking. Recently, I addressed a hospital board that was struggling with the "prevention" mentality. I attempted to show them that a typical inpatient stay, what they have always regarded as their "bread and butter" service, would be viewed as a loss if they were serving on the board of an insurance carrier or most IDNs. And soon the same thinking will apply to outpatient settings. The only solution? Further institutional consolidation to concentrate the losses in fewer, higher-cost settings. Consolidation, of course, means the death of some institutions. No wonder many trustees are confused.

Strategic Direction

Boards must ask themselves whether a consensus exists among members on strategic priorities and directions. Often trustee votes on narrow, everyday topics are carefully counted and duly recorded while no one asks if the board is together on the most important issues. Developing consensus is rarely easy, but it is best achieved by frequent, intense reflections on strategies rather than operational issues.

Network Role

Trustees must also clarify their organization's role vis-a-vis other institutions. If an institution is already part of a network, do the trustees understand their unique role in it? Do they know anything about the other network players? Have they met with the boards of the other institutions? Are they actively trying to reduce duplicated facilities or services? Are they considering new ventures that only the network could create or sustain?

Of course, pursuing these suggestions can help any board in any circumstances. The important point now is that if the board is not functioning well under current conditions, it is much more likely to fail under the new demands imposed by reform.

The Payoff

If Catholic healthcare institutions effect significant board improvement in some of the ways discussed here, what can we expect to happen?

First, the institutions will operate more effectively, meet their mission objectives more successfully, and carry a good deal more strength and power into the complicated negotiations that will precede IDN formation.

Second, the best trustees will become leading candidates for the new IDN board. Their performance will be vital to the preservation of our institutions' roles and missions in the new organizations.

Third, we will have improved our own job performance as trustees, managers, or consultants and, most important, improved the quality of service we offer to those in our care.

Mr. Scavotto is president, Health Management and Governance, Inc., St. Louis.

TRUSTEES' ROLE CHANGING YET TIMELESS

Since my first experience as a board member — at Misericordia Hospital in Philadelphia in 1959 — change and adaptations have been on the agenda of all the boards on which I have served. I do not see any lessening of this movement. Rather, change is occurring at an accelerated pace.

Mercy Health Corporation (a subsidiary of Eastern Mercy Health System, Radnor, PA) has grown from one hospital in 1918 to a complex organization in 1994, as it moves into integrated delivery to provide a seamless continuum of health services. More than ever before, we trustees are required to be dedicated to our jobs and willing to give a lot of time to preparing and understanding the milieu in which we are functioning.

As trustees, we also must be much more alert in analyzing the ways corporations will be set up as we prepare for the changes brought on by healthcare reform legislation.

Role of Lay Directors

When I first became a trustee, the only members of the corporation board were the major superior and her council. An advisory board of laypersons contributed their expertise in medicine, law, banking, construction, and other areas.Today, the laity are full members of the board just as the sisters are. Laypeople participate on all the board committees. They also feel more responsible for the mission and values of the organization than in the early days, when those concerns were considered the responsibility of the sisters.

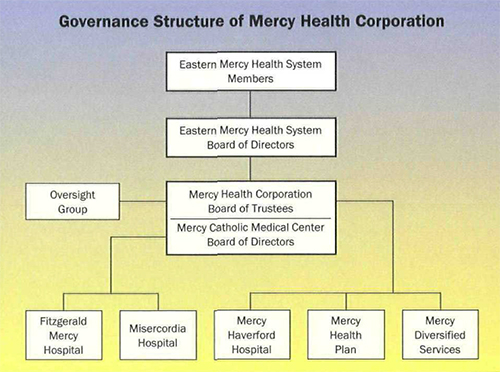

Oversight Group

But, as was impressed on me from the beginning, the religious institute is a public juridic person in the Church, governed by the major superior and her council. The religious institute's responsibility for matters of faith and administration is clearly spelled out in canon law. To ensure that this reponsibility will be carried out for Mercy Health Corporation, regardless of sister representation on the corporation's board, an Oversight Group was established by the congregation and the corporation (see Figure, below). The major superior and council of the regional community of Merion has this separate and distinct function as members of the Oversight Group.

Preparing Sister Trustees

To prepare sisters for the complexities of serving as trustees, a group of sisters from the congregation's academies, college, and hospitals designed a training program in 1986. At monthly workshops sisters interested in becoming trustees heard presentations from hospital executives and experienced sister trustees. Then, as interns, they observed boards in action. This training program helped sisters become more effective trustees.Meaning of Trusteeship Today

The charism of the Religious Sisters of Mercy — service to the poor, sick, and disadvantaged — is always considered by our boards today. For me, being a trustee is a privilege — a wonderful opportunity to influence the ministry and move things in a Christ-like direction. Through all the changes in healthcare today, I see the same principles enduring. We are called to embrace and be loyal to our mission and charism.Sr. Mary Agnes Connor, RSM

Member, Board of Trustees

Mercy Health Corporation

Bala Cynwyd, PA

MISSION STATEMENT: KEY QUESTIONS

- Is your own mission statement primarily descriptive? If so, change it so that it is primarily directive — a clear, specific charge reflecting the wishes of the sponsoring group.

- If prospective trustees read the mission statement carefully, will they understand what they are being asked to do? Will they care?

- How well does the institution's mission statement fit with mission statements of other organization's with whom it is affiliated?

- Does the stated mission conflict with that of any of these organizations?

- How can trustees reconcile any such contradictions?