BY: JOHN TUOHEY, Ph.D., and NICHOLAS J. KOCKLER, Ph.D., M.S.

Samuel1 is a 36-year-old gentleman who was building a home with his girlfriend of six years. One day she drove out to the construction site and found him on the ground, not breathing, and pulseless. She dialed 911 and initiated CPR as best she could. When the EMTs arrived, they took over, managed to get a heartbeat and maintained his breathing on the way to the hospital. Upon admission he was put on a mechanical ventilator and admitted to the ICU. The hypothermia protocol was initiated in the hope of minimizing brain damage. Not knowing how long he had been down, it was impossible to determine his chances for recovery. Passive warming was initiated after 24 hours. After more than 72 hours from the time of admission, the senior resident informed the patient's girlfriend that Samuel's prospects for recovery seemed very poor. She did not have to decide anything right that moment, he said, but she should begin to give some thought to what Samuel would want in this circumstance.

Inclined to continue on for a few more days but not knowing what to do, the girlfriend asked the senior resident to call Samuel's mother, who was out of state. The mother suggested he call Samuel's wife, also out of state. Samuel's wife had left the marriage seven years previously, taking their son. Although she had filed for divorce years ago, she had not followed through.

The girlfriend was distressed to learn of the wife, and more distressed to learn the wife asked that Samuel be taken off the ventilator. Samuel's mother supported the wife's decision.

The senior resident called for an ethics consultation: "Who is my patient's decision-maker?"

For most questions about surrogate decision-making, an ethics consultation gives a recommendation for a course of action. No one would fault the ethicist if he were to answer that, under the law, the wife is the patient's decision-maker and he can take Samuel off the ventilator.

He might, however, have opined that although the law says it is the wife, as long as he documents that in light of the years of separation and attempt to divorce on the part of the wife, he can allow the girlfriend to decide.

Both responses answer the question, and both are defensible even if contrary to each other. In our paradigm for graduate medical education, neither is satisfactory by itself because neither gives the resident the tools needed to be more than a medical technician who executes decisions made by surrogates. As we phrase it, simply giving a recommendation does not give the resident the ethics competencies needed to be a professional. That, we believe, is the fundamental purpose of ethics education in a teaching hospital.

The goal and purpose of a teaching hospital, such as those within Providence Health & Services in Oregon, is to be that place "where medical knowledge continuously evolves and new cures and treatments are found. They are where critical community services, such as trauma and burn centers, always stand ready. They are the training ground for more than 100,000 new physicians and other health professionals each year."2 In short, a teaching hospital is where newly graduated medical students demonstrate the technical skills they have acquired and, under the guidance of the medical faculty and the hospital staff, refine and improve their techniques to be the most highly skilled physicians possible.

At the Providence Center for Health Care Ethics in Portland, Ore., a regional ethics resource for consultation and education, we provide a variety of educational opportunities for three residency programs: two in internal medicine and one in family medicine. The Ethics Center's faculty consists of two professionally trained ethicists and one physician ethicist who teach noon conferences, ethics rounds, medical grand rounds, special open forums and other educational sessions. The Ethics Center also manages three funded lectureships and offers a range of educational opportunities beyond the residency programs, especially through our Ethics Core Curriculum Program. The ethics consultation service is staffed and supervised by the ethicists of the Ethics Center, too.

In our approach, ethics and ethics education within a residency program are not limited to being in service to answering narrow legal or ethical questions. Ethics and ethics education can, and we believe should, instead serve to help transform one's skill or teché into the professional application of that skill: into what we call praxis. This is a distinct approach that may be different from how other residency programs approach ethics education, precisely because it goes beyond narrow types of questions. We built our ethics education programming around the philosophy that ethics education during residency (ethos) helps to transform clinical skills (techné) into professional caregiving and medical practice (praxis). By this we mean that a resident learns not only how to apply medicine to obtain clinical benefit, but he also is capable of entering into and managing the challenges and nuances of interpersonal, therapeutic relationships. It is not enough to know if Samuel is a good candidate for the hypothermia protocol or what the law says about surrogate decision-making. The resident needs to learn how and why the therapeutic relationship he shares with the patient shapes the importance of consent in this particular case.

We believe that this philosophical approach to ethics education is fully consistent with Providence's Catholic identity. The concerns of Catholic ethics center on right relationships; our hope is that through ethics, therapeutic relationships in our hospitals remain in or return to a state of rightness. We believe that this is essential to the healing of the whole person as well as the flourishing of all whom we encounter in our hospitals — provider, patient, and family member alike.

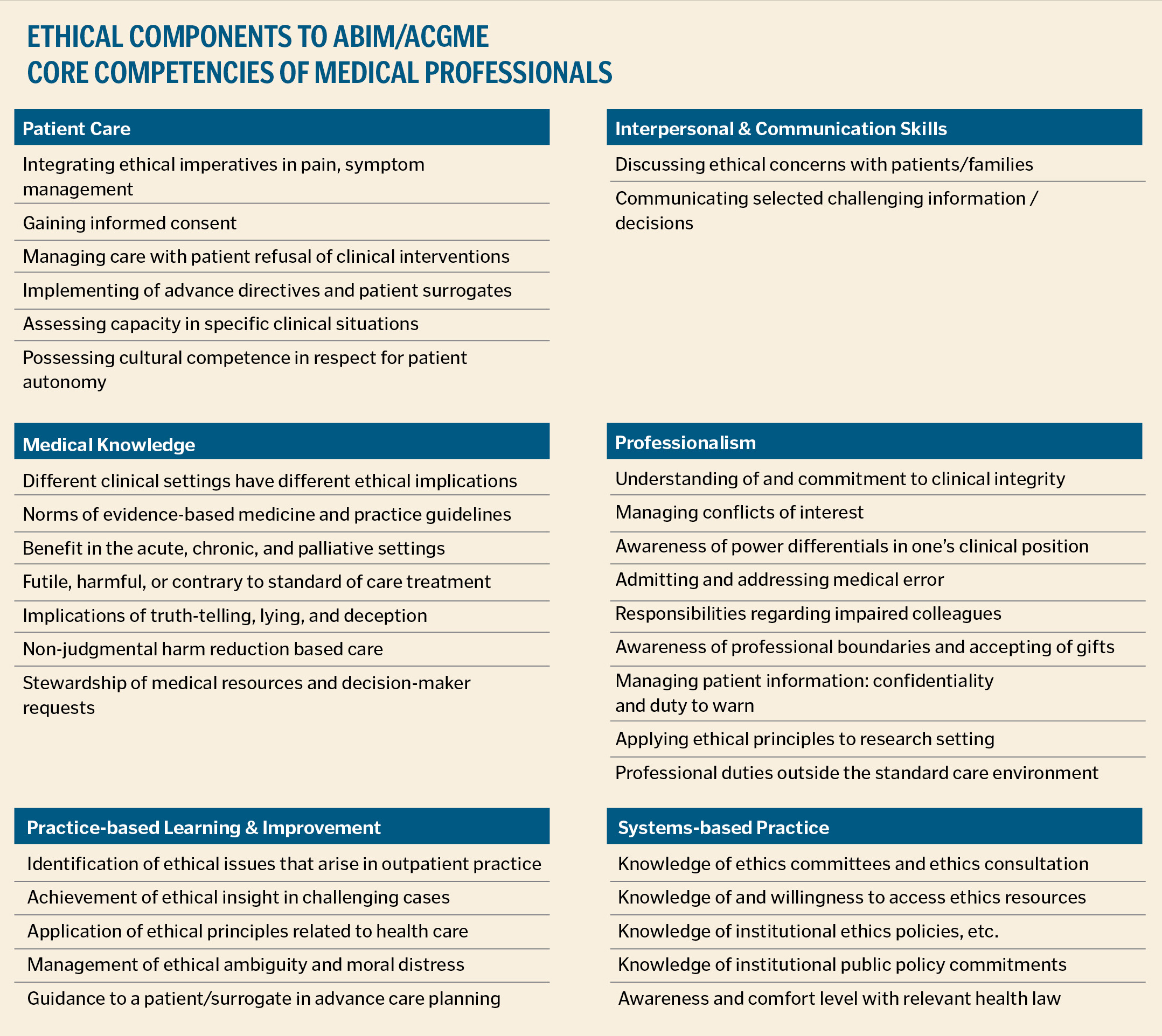

Professionalism is one of the six core competency domains identified by the American Board of Medical Specialties and the Accreditation Council for General Medical Education. The others are patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills and systems-based practice. For this reason, it sometimes happens that the ethics content of residency ethics education focuses on issues related to professionalism. We think this approach is too narrow. In many respects, professionalism is akin to what we might call clinical etiquette: for example, not lying to or over-charging a patient, or not becoming emotionally involved with a patient during therapy. However, we envision professionalism not simply as one competency domain among others; rather, it refers to the integration of all six domains into a synthesis found in the therapeutic relationship — the right practice of medicine by medical professionals.

At Providence, we have developed several ethics components to each of these core competency domains (see Table 1). This explicit identification of ethical components to these domains is another distinct element of our approach to ethics education, and it gives us, as it were, learning outcomes for our programs in graduate medical education. In fact, our approach is consonant with the forthcoming "next accreditation system," which is scheduled to begin implementation throughout graduate medical education in July 2013.3

How do we accomplish this transformation into professional practice? We see ethos as transforming clinical techné into professional praxis through the achievement of what we think are the three ethics competencies to be taught in graduate medical education. First, there is the practice of practical wisdom by which the clinician may more readily avoid acting in a default-type, unreflective manner to a situation. Next, there is exercise of moral freedom by which the clinician enjoys the confidence that moral distress can erode. Finally, there is the demonstration of integrity in medical practice, which helps the clinician to identify and minimize the moral hazards at play in a case.4

PRACTICAL WISDOM

An important goal of graduate medical ethics education is the promotion of practical wisdom and the minimizing of its opposite, which is acting in a default or unreflective way. One place where this can happen is in an ethics consultation. In our setting, ethics consultation takes on a role that is less about answering a question or offering a recommendation than it is about coaching the resident in right thinking about the question he has raised. Another opportunity for this ethics coaching is an ethics rotation during which the resident spends approximately one to two weeks shadowing and participating in the work of the ethicist across a variety of settings.

Other examples include ICU ethics and ward ethics rounds wherein the ethicist and the residents set aside opportunities for real-time ethical discernment of the cases they see. Concretely, this form of coaching for practical wisdom is explored using the more classical image of prudentia, representing practical wisdom, that calls to mind the use of reason, memory, foresight, circumspection, determining the relative importance of a variety of facts related to the case, the ability to be shrewd or clever if necessary, and exercising caution. This is similar to the notion of theological discernment: " 'Discernment,' as we generally use the term, refers to the quality of perception and the capacity to discriminate degrees of importance among various features before making a judgment. The ability to discern involves keenness of perception, sensitivities, affectivities, and capacities for empathy, subtlety, and imagination."5 Through our ethics consultation service, we bring the skills necessary for discernment to bear on the "value-laden issues"6 prompting a consult request.

In Samuel's case, the ethicist might ask the resident why he wants to know who the decision-maker should be. It may be that he merely wants to make sure he follows the law (default) or seeks the most straightforward and least controversial approach (avoid moral distress). The ethicist should help the resident exercise practical wisdom, as distinct from the clinical or legal reason, for determining the correct surrogate by exploring the moral role of consent in the therapeutic relationship. Using foresight, it is plain that whoever gets to decide will have a profound influence on the outcome: the patient will live or die. Being more circumspect, the resident comes to see consent is not simply related to performing or not performing a medical intervention, but rather has to do with permission to touch someone, touching being the most profound exercise of the healing arts in the therapeutic relationship. By not simply defaulting to the law or wanting to avoid moral distress at all costs, he can use reflection on how he might, perhaps with a degree of shrewdness and caution, see his techné, or clinical skills, become praxis, or professional caregiving.

The significance of touch is explored more fully in didactic sessions, such as a noon conference, where permission to touch is related to consent and the importance of trusting the person (patient or surrogate) who gives the resident permission to touch the patient in a healing manner.

MORAL FREEDOM

Enhancing moral freedom can occur through a variety of mechanisms:

- Knowing the basis for the right course of action

- Having language to describe the ethical issues or rationale at play

- Recognizing the structures or barriers preventing follow-through on the right course of action

Moral freedom may also mean the moral confidence one needs in order to act. These can be passed on through didactic education sessions, such as regular noon conferences which follow an 18-session rotating curriculum to capture key topics during all three years of residency. Other opportunities include morning reports and medical grand rounds. These sessions are aimed at passing on the ethics-specific skills and knowledge needed to assist the residents especially in resolving the moral distress described above. We draw the content for these sessions from our particular model for clinical ethics decision-making, topics related to the medical board exam and those ethics components we have identified with each of the six American Board of Medical Specialties and Accreditation Council for General Medical Education competency domains for medical education.

In the case above, if the resident makes what he considers to be the prudent decision to work with the patient's girlfriend, the ethicist may ask the resident, "So when the wife tells you she has spoken to a lawyer and insists on being the decision-maker, what are you going to say?"

In this the ethicist can appeal to previously presented lessons from the more formal settings. Without the ethical skills of deductive reasoning and ethical language, not simply the legal language for understanding consent (as well as the ability to demonstrate an ability to be shrewd in language choice, to be sure), the resident could succumb to the pressure to shift back to the default, legal approach, and experience the moral distress of not being able to follow through on what is believed to be the right way to proceed with this patient.

INTEGRITY IN MEDICAL PRACTICE

Ethical integrity in medical practice can be characterized as honesty, dependability, fairness, and accountability in the thoughts and actions of medical professionals.7 Insight into this personal sense of integrity is acquired across the spectrum of the educational experience. However, this component of graduate medical education is largely practiced through consistent use of the consultation model used at Providence to think through ethically challenging cases. Of course, this model is used during ethics consultations, but it is also utilized as a pedagogical tool during case presentations in more formal didactic settings.8 This model explicitly applies our definition of integrity as a physician's

- Honesty in the practice of medicine

- Dependability to benefit the patient medically

- Fairness to the autonomy of the patient

- Willingness and ability to explain the course of action in light of other relevant justice or nonmaleficence obligations.

We see this as a kind of juggling act whereby it is not sufficient to simply ask what principle or concern rules the day. Integrity is measured by our ability to address and balance attention to all applicable principles across all spheres of concern in any given case.

In the present case, given the length of time passed and the absence of any good prognostic indicators, honesty in medicine will suggest it is time perhaps to shift to another modality of care, such as comfort care. Comfort care may also demonstrate dependability to benefit a patient by pursuing what may be the only benefit available: palliative benefit.

The girlfriend may challenge this, suggesting such a care plan is not good for him, and our concern for her may become a moral hazard to benefit if we shift our focus away from the patient to the needs of the girlfriend.

Having said all that, Samuel, the patient, does have a son, and suppose the wife wants to put a plan on hold until that son can see his father for the last time? It will be difficult to discern if there is some justice obligation to act on behalf of the son and wait, or if the patient would not consent to getting non-beneficial care for someone he does not know well. To act with integrity is to embrace the characteristics of integrity in a juggling or balancing of these seemingly competing and complementary concerns. It is not difficult to see the moral hazards entailed.

CONCLUSION

Teaching hospitals are an essential part of the education and training process by which women and men become talented, skilled physicians. For us, it is also the place where those talents and skills are transformed, through education in ethics and the humanities, to professional caregiving, transformed from skilled technicians to interpersonal professionals in complex therapeutic relationships. Through a comprehensive and integrated program across different educational settings, we believe we achieve that transformative goal by enhancing the graduate medical education experience with the three components of ethics education. These provide opportunities to gain insight into acting out of a context of practical wisdom that avoids default decision-making, enhances moral freedom and minimizes moral distress and ensures the pursuit of integrity to overcome or navigate around moral hazards. In this sense, we believe our residents complete their program with a professionalism that is more than etiquette and more than knowing how to answer an ethical or legal question.

With the opportunity to transform skill through ethics education, as described above, our residents become true caregivers, fully invested in the quality of their very human, and very complex, therapeutic relationships.

JOHN F. TUOHEY is regional director of Providence Center for Health Care Ethics, Providence St. Vincent Medical Center, Portland, Ore., and holds the endowed chair in applied health care ethics.

NICHOLAS J. KOCKLER is senior ethicist at the Providence Center for Health Care Ethics, Providence Portland Medical Center, Portland, Ore.

NOTES

- Names and details of this case have been changed or omitted to protect the identity of those involved.

- Taken from the Association of American Medical Colleges, www.aamc.org/about/teachinghospitals/70242/teaching_hospitals.html.

- Thomas J. Nasca, et al., "The Next GME Accreditation System — Rationale and Benefits," New England Journal of Medicine, nejm.org, published Feb. 22, 2012, accessed March 1, 2012.

- We define moral hazards as those barriers, obstacles or disincentives to recognizing or fulfilling an ethical obligation.

- Richard Gula, Reason Informed by Faith (Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989), 315.

- American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation (Glenview, Ill., ASBH, 1998), 3.

- See Laura L. Nash, Good Intentions Aside: A Manager's Guide to Resolving Ethical Problems (Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 1993), 33-35. Nash identifies her fourth characteristic of integrity as pragmatism — ability to make a concrete contribution. To our way of thinking, this characteristic belongs to the ethics enterprise itself, and not to an element of it. In our experience, accountability, which we understand as the availability and ability to explain one's actions in light of other considerations more at the periphery but still relevant to the ethical challenge, is an important characteristic of deciding with integrity. So in this case, the care team will have to account for or explain why it chooses to allow the girlfriend to decide and not the wife as legally established. The decision cannot simply ignore that legal dimension, but rather, to act with integrity, will need to be able to explain why it will not follow it.

- See, John Tuohey, "Ethics Consultation in Portland," Health Progress 87 (March-April 2006): 36-41.

ETHICS TRAINING FOR MEDICAL INTERNS/RESIDENTS IN THE MERCY HEALTH SYSTEM

By FR. PETER A. CLARK, SJ

The Mercy Health System, Philadelphia, is unique in Catholic health care in that we have three sets of medical interns and residents in three acute care hospitals, with specialties in internal medicine, radiology, general surgery and family medicine. Many of our residents are foreign-born, and while this has presented us with some interesting cultural and educational issues over the years, the training and skills of these medical interns and residents are exceptional.

The diversity of ethical training that many of the interns and residents received in their home countries challenged us to think of new ways to increase their ethical skills so that when they finish their program, they are well-trained medical professionals with a solid ethics background. Fr. John Tuohey's article is quite clear that ethics and ethics education should transform the skills of medical interns and residents into the professional application of those skills: what he calls praxis. This is accomplished in the Mercy Health System through a rigorous, three-year ethics core curriculum.

Topics covered include the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Services, advance directives, confidentiality, giving bad news, medical futility, etc. The interns and residents also take part in ethics grand rounds, noon conferences and weekly interdisciplinary ethics teaching rounds.

In 2003, the Mercy Health System developed the weekly interdisciplinary ethics teaching rounds as a new training method. The purpose is threefold: first, to better enable health care providers in supplying excellent care to their patients; second, to reduce the number of ethics consultations present within the hospital system; and third, to aid interns and residents in their bioethical education in hopes of helping them focus on the best interests of their patients.

Ethics teaching rounds accomplish these goals by addressing patients' specific ethical issues. An interdisciplinary team (physician, nurse, ethicist, pharmacist, social worker, pastoral care, nutrition, risk managers, the vice president of mission, etc.) assembled by the hospital's ethics committee takes part in these discussions and makes recommendations pertaining to patients' future care plans. They discuss numerous legal and bioethical issues, such as informed consent, medical futility, competency, incompetency, quality of life, proper use of resources, end-of-life care, surrogate consent, distributive justice, confidentiality, etc. They also explain the ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, fidelity, confidentiality and privacy — the hope is that the young physicians will absorb the ideas and use them when dealing with patients.

We stress a holistic approach to care, that is, the need to address patients as whole persons. All aspects of personhood (body, mind, spirit) ought to be considered with these rounds. It is the goal of ethics teaching rounds to help young physicians define their patients as more than persons with illnesses. Instead, patients are defined as persons who are in an unfortunate state of bad health, and, because of their condition, must be cared for with compassion, dignity and understanding.

All pertinent aspects of patients' lives should be addressed when attempting to provide excellent medical care. In other words, a patient's medical history, personal attitudes, religious beliefs, financial situation, intellectual capacity, spirituality, social tendencies, etc. should all play a role in his or her care plan. Often, young physicians focus too much attention on a patient's pronounced disease and not enough attention on the underlying causes, such as poor nutrition, addiction, stress, etc. These physicians fail to understand patients as whole persons, that is, they fail to address all the pertinent aspects of a patient's life when attempting to diagnose.

Ethics teaching rounds stress the need for health care providers to understand the big picture, that is, health care providers must condition themselves to identify health as a state of being affected by a person's body, mind, and spirit. Ethics teaching rounds accomplish this goal in different ways. The first is simply by using a patient's name. By referring to a patient as "Mrs. Johnson" rather than as "the 57-year-old female" or "the patient in room 32," the clinician instantly establishes a sense of that patient's personhood.

The challenging nature of the interdisciplinary ethics team also helps guide students' understanding of patients as persons composed of a body, mind and spirit. When discussing a case during ethics teaching rounds, the interdisciplinary ethics team asks students questions related to that patient's religious beliefs, financial situation, personal attitudes, etc. This practice teaches the health care provider to consider all pertinent aspects of a patient's life when caring for him/her — and emphasizes the need for a complete medical and personal history for all patients. In this way, Ethics teaching rounds help create a "person-treating-person" mentality, which is the starting point of the very important doctor-patient relationship based on trust and equality.

Although the emphasis is on teaching interns and residents during ethics teaching rounds, it must be stated that these individuals are also called to play the role of teacher. The interdisciplinary ethics team merely focuses discussion about ethical issues and makes recommendations for patients' care plans. It is the interns and residents who present patients' cases, explain the ethical issues, take part in discussion of resolving these ethical issues and carry out the solutions.

In a 1998 article in JAMA, James A. Tacci, MD, said he believes the resident-as-teacher role should be used more in today's clinical settings. He states, "Unfortunately, residents often assume teaching responsibilities with little formal preparation, and few programs set aside time and other resources to develop residents' teaching skills," and "All residency programs would be well served if they were to develop a systematic, ongoing program that teaches residents how to teach."

Tacci believes it is important for residents and students to be defined as "teachers, students, caregivers, and team members."1 Ethics teaching rounds follow this philosophy by making interns and residents as the focal point, the individuals who control the meetings and are simply aided by the interdisciplinary ethics team.

This interdisciplinary model of ethics teaching has not only increased the professionalism of our interns and residents, but has served the best interest of our patients in numerous ways. Ethics consultations have decreased by over 50 percent, the notion of a team approach to patient care has become a standard and the quality of care for our patients has increased considerably. The end result is that in Mercy's acute care hospitals, Catholic health care has been marked by a spirit of mutual respect among caregivers that disposes them to deal with those they serve and their families with the compassion of Christ, sensitive to their vulnerability at a time of special need.2

FR. PETER A. CLARK, SJ, is a professor in the Department of Theology and Religious Studies and director of the Institute of Catholic Bioethics at St. Joseph University, Philadelphia. He is a bioethicist for the Mercy Health System in Philadelphia.

NOTES

- James A. Tacci, "The Resident as Teacher: A Neglected Role," JAMA 1998; 280 (10): 934.

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services, 5th edition, December 2009, Directive 2.

SAMUEL'S CASE:

HOW THE PROCESS WORKED

The request for this consult originated with a page to the ethicist from the senior resident, who explained the situation. As it was not urgent, both agreed the best approach would be to wait a day and discuss it as a team at the ICU ethics rounds meeting that week. During that discussion, in which the acute care manager and quality care representative participated, there was a free-flowing conversation about how easy it would be to just follow the law and let the wife decide.

As the resident pointed out, "It's hard to take consent from someone who is not interested in the facts of the patient." This led to a discussion of the importance of consent as "permission to touch" more than "permission to proceed." We then strategized on how to talk with Samuel's wife in a way that was respectful, but also clear that there was discomfort with simply moving to comfort care so quickly.

The decision was made that the patient's interest was best served not by choosing among competing candidates, but rather to proceed on a strictly clinical basis. As there was no need to do anything right that moment, giving the patient a larger window for recovery was consistent with common practice.

INTEGRATING ETHICS INTO THE RESIDENCY MODEL OF PHYSICIAN EDUCATION

By MARK REPENSHEK, Ph.D.

and ERIN O'TOOL, MD

It is often the case in health care systems that programs develop organically, and, unless prompted, we may not reflect on the original intent of the program as it presently exists. That is the case with medical residency programs at Columbia St. Mary's Health System in Milwaukee, to the extent to which ethics is integrated in those residencies. So it is with gratitude that we offer this piece as an opportunity to reflect on a very successful partnership between ethics, family medicine residency and our joint obstetrics and gynecology residency.

Columbia St. Mary's has about 15 residents every year, usually divided almost evenly between obstetrics-gynecology and family medicine. As with all accredited residency programs, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education sets the context for the residency's mission, namely "to improve health care by assessing and advancing the quality of resident physicians' education … ."

Yet, this mission statement alone rings a bit hollow unless program content is given to what constitutes quality for the residents' education. From the perspective of Columbia St. Mary's, this requires a quasi-formative approach with ethics integrated throughout the residents' years with us.

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) readily acknowledges the inherently social aspects of healing in its mission statement, "the AAFP is to improve the health of patients, families, and communities … ." The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists echoes this statement, recognizing "Obstetrician-gynecologists, as members of the medical profession, have ethical responsibilities not only to patients, but also to society, to other health professionals and to themselves." Additionally, the AAFP commits its membership to care that is "equitable for all people; centered on the whole person within the context of family and community … and grounded in respect and compassion for the individual."

Not surprisingly, the General Introduction to the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services recognizes these same values inherent to the profession of healing, noting, "the dialogue between medical science and Christian faith has for its primary purpose the common good of all human persons." It is our view that ethics provides an optimal venue to explore this dialogue, so long as opportunities exist.

NEW RESIDENT ORIENTATION

Knowing that our residents with be with us for the next three to four years, depending on their program, new resident orientation is a critical opportunity to set the tone for the collaboration among mission, ethics and the resident. Amidst the barrage of information the resident is exposed to in the first week of his or her tenure with us, ethics devotes time to discussing cases that linger with residents as they move through their training. The case-based method is a helpful context, as John Tuohey and Nicholas Kockler illustrate, to help the residents through a critical thinking process that will test more than their clinical knowledge. If nothing else, the new resident, anxious to hit the floors and care for "real patients," is made aware of the support ethics can offer as part of the infrastructure of care at Columbia St. Mary's.

Shortly after orientation, the family medicine residents are required to complete Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) certification. Rather than relying solely on the ethics section of the American Heart Association's manual, ethics committee presence at the ACLS certification course to discuss challenging cases, ethics policy on Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) and community DNR orders, protocol jointly developed with the medical staff on Code Status Order Sets, creates another context for exploring the intersection between clinical medicine and the ethics of that profession.

DAILY ROUNDS

Morning report is a tradition within our family medicine program in which the intern provides a full review of the most valuable case, from an educational standpoint, based on the previous set of evening admissions. From chief complaint to differential diagnosis to impression and plan, the team of residents uses a case-based medical model to better educate themselves on "What would I have done in this situation?" The senior residents offer insight and instruction along the way to guide the less experienced interns and second-year residents.

As part of this daily process, ethics maintains a presence that allows for exploration of the ethical aspects of difficult cases alluded to in Fr. Tuohey's and Kockler's example. In this way, the questions explored do not solely reside within a traditional model of discerning the correct diagnosis, but rather consider the person affected by disease in the context of his or her family and community. The resident, from the first year on, is exposed to a way of thinking that incorporates the moral questions — What ought we to do? What is the right treatment among options for this patient? How ought we to journey with this patient/family through this hospitalization and this disease process?— into analytical models of assessment and diagnosis. There is an additional benefit to this process; namely, it allows the resident to feel safe asking these ought questions when multiple solutions seem appropriate clinically. It also allows the resident to explore these ought questions when significant tensions exist among appropriate clinical approaches.

ETHICS GRAND ROUNDS

The relationships established through daily rounds form the foundation for collaboration between ethics and residents in the more formal Clinical Medical Education Ethics Grand Rounds. This forum allows the senior resident to present a case with a member of the ethics committee in which the resident called for ethics consultation and discuss the ethical aspects of the case with their physician colleagues. The traditional model of peer review becomes the template to elevate discussion beyond morbidity and mortality to a contemplation of what care ought to be delivered. In this way, Ethics grand rounds make relevant the non-clinical dimensions essential to quality patient care. More importantly perhaps, it fosters a culture of care delivery that is interdisciplinary — advocating for ethics consultation, where appropriate, as naturally as neurology, cardiology or pulmonary, for the health and well-being of the patient.

PALLIATIVE CARE AND ETHICS

For the family medicine resident ready to move into practice, remaining clinically relevant to the patient through the patient's acute or chronic event means remaining on that journey with the patient. Family medicine is in the unfortunate position of being positioned "outside" the systematic care of patients in the acute inpatient setting. All the nuances of the relationship between patient and physician may also fall victim to this "outside" positioning. The family medicine rotation in ethics and palliative care reinforces the conviction that the family medicine physician, in journeying with his or her patient, may be the most relevant person to guide care that aligns what can be done with what ought to be done

The intention of this piece about Columbia St. Mary's program is merely to provide an example of being intentional about integrating Catholic health care ethics into the physician residency model of education. The larger idea is this: The patient is part of an intricately woven social fabric in which his or her disease manifests, rather than solely a host to a disease subject to diagnosis and treatment. Taking a formative approach while teaching this important concept to residents and interns facilitates a forum for the new physician to refine his or her intrinsic ethical sensibilities in patient care.