BY: MICHAEL PANICOLA, PhD and RON HAMEL, PhD

Health care in the United States is in a state of major transformation, the likes of which perhaps we have never seen. In the volume-to-value transition, payers already are beginning to adopt value-based reimbursement models; employers are demanding more return on their considerable investment in employee health; providers are consolidating in strategic partnerships; consumers are becoming more cost-conscious; start-ups and deep-pocket technology companies are challenging the status quo; and advocates for price transparency are exposing the irrationally wide variation in health costs.

This transition reveals some very encouraging trends. The shift to population health brings wellness, prevention, coordinated care and chronic disease management to the forefront. Improved delivery structures and a better alignment of financial incentives toward value and away from volume are in evidence. More heartening, the number of uninsured Americans continues to drop due to the improving economy, Medicaid expansion and health care marketplaces offering affordable plans for individuals and families. Such encouraging trends have special resonance for Catholic health care: The promise of creating a more just, sustainable health care system in line with a Catholic-Christian vision of health care has the potential for strengthening Catholic identity.

There are, however, trends that are concerning. While the percentage of uninsured people is declining, the number of those underinsured is increasing. Almost 40 percent of individuals under 65 years of age now have a high-deductible health plan, which means that while they have health coverage, they may not have the funds to reach the deductible, forcing them to forgo care or needed medications. The problem stretches beyond low- and moderate-income individuals, so that in the majority of U.S. households, the percentage of income that goes to pay health care costs is still on the rise.

Health care providers have challenges of their own. The health care sector overall, and not-for-profit health systems in particular, have rising expenses with weaker reimbursements, which pushes down operating margins.1 This has led, in part, to a rash of mergers and acquisitions whereby highly capitalized, larger health systems get stronger, while less-capitalized, smaller health systems and freestanding hospitals, especially rural and critical access hospitals, get weaker. Catholic mega-systems have revenues close to or surpassing those of for-profit systems, and it is difficult to keep abreast of the proliferation of Catholic and non-Catholic partnerships.

Rapid consolidation is not unique to health care — think banks, airlines, cell phone carriers and car manufacturers. As many financial analysts tell us, consolidations may be necessary, because size and scale are critical for future success. Still, Catholic health care never has been in this for the money or merely to survive. It always has been, and still should be, about furthering the healing ministry of Jesus by living out our fundamental value commitments, which are the true measure of our identity and at stake in every merger, acquisition and partnership. We must ask ourselves if we are considering the impact on identity when Catholic health care is being reshaped in unprecedented ways. In our desire to ensure long-term sustainability, are we chasing the market and disregarding the impact this could have on identity? Are we asking how growth opportunities further our ability to live out our fundamental value commitments, or are we focusing merely on the narrower cooperation issues that could derail the transaction?

FUNDAMENTAL VALUE COMMITMENTS

Catholic health care is motivated and defined by its faith in the redemptive act of Jesus Christ. Its mission is to reveal God's healing and reconciling presence to the sick and suffering of the community. Rooted in the Gospel, our values are expressed in the organizational documents of Catholic health ministries and make up the substance of the Catholic Health Association's "Shared Statement of Identity."

As we pursue new business arrangements, we must ensure we are truly advancing the mission of Catholic health care. This requires that we remain vigilant and deliberate about our fundamental value commitments and about who we are as ministry. An added reason to do this is the call of Pope Francis, who has challenged the entire Catholic-Christian community to a deepened living out of the Gospel values. The pope has taken up certain themes that reorient us to core aspects of our fundamental value commitments, and they must be taken into account when considering a merger, acquisition or partnership.

The first theme is that of mercy and hope. From the beginning of his papacy, Francis has preached that the church mediates God's love of humanity by being a sign of mercy and hope, especially to people who are suffering, lost and in need of help. To be that sign of mercy and hope, Catholic health care must locate itself in the midst of suffering and minister to those who suffer. This is what we are weighing when considering a new business arrangement — whether the merger, acquisition or partnership gets us closer to the suffering that needs God's mercy and hope. Are we looking at whether the reconstituted health system and the services it offers will further our ability to reveal God's healing and reconciling presence to the sick and suffering of the community?

Pope Francis' second theme is that of care for the poor. Perhaps more than any pope in recent history, Francis is intimately familiar with and committed to the plight of the poor among us. Indeed, he has said he wants a "Church which is poor and for the poor." The significance of the pope's insistence on the preferential option for the poor in Catholic health care cannot be mistaken. The poor need to be a primary focus of our ministry if we are to be true to our mission. Any organizational decisions we make — about community services, consolidation of jobs or new business arrangements — have to be considered in light of their impact on the poor. If the best business decision is the wrong ministerial decision, we have to look for another way. When we seek to acquire, merge or partner with another organization, are we asking how the new business arrangement will further our ability to care for the poor? Are we looking to go into medically underserved communities, especially rural and inner-city areas, or are we only considering growth opportunities with prospective partners that have significant revenues, positive margins and good payer mixes?

The third theme is that of social justice. While continuing to address traditional moral issues, Pope Francis has raised our awareness of the profound issues of poverty, racial inequality, income disparity, climate change, trafficking and migrants/refugees as subjects we must engage if we are to broaden the scope of our moral life.

The emphasis on social justice is important for Catholic health care in three ways. First, we need to be models of justice within our own organizations in terms of how we treat our employees, care for our patients, and act as corporate citizens in terms of the investment of our substantial resources and our care for the environment. Second, we need to be a force for good in our communities by advocating for justice and working with others to undo and correct injustices. Finally, we need to be aware of the broader social justice issues engendered by new business arrangements and attend to these as much as we attend to issues related to cooperation. Do we look at how a merger, acquisition or partnership will affect employees' job stability, wages and benefits? Do we consider the impact on local communities and the increase in our environmental footprint when we expand the size of our systems? Are we able to evaluate the prospective partner from a moral perspective that extends beyond their involvement in abortion, contraception and sterilization?

DISCERNMENT AND INTEGRATION

As we continue to reshape the ministry of Catholic health care, we must never let the need for size and sustainability blind us to the importance of our fundamental value commitments. Living out these commitments is a necessary condition for realizing our mission of revealing God's healing and reconciling presence to the sick and suffering of the community. Consequently, every new business arrangement undertaken by a Catholic health care organization must be evaluated on the basis of whether it allows us to live out these commitments.

Making this the case in new business arrangements is no easy task. It will take senior leaders who are cognizant of, sensitive to and willing to stand up for the value commitments when it might be easier to set them aside in the interest of closing the deal. It is going to take a better, more systematic approach or process to discernment on the front end and integration on the back end.

To address the concern around mission/ethics discernment and integration in new business arrangements, we outline the following process for consideration, with the caveat that it be taken as a first attempt that others within Catholic health care will refine, expand upon and adapt to the unique circumstances and cultures of their organizations. Engaging the process will not guarantee every merger, acquisition or partnership we enter into will advance the Catholic health care mission. However, it will ensure that we ask necessary questions for understanding our motivations and that we keep our fundamental value commitments at the center of our decisions.

When a Catholic health care organization — often abbreviated to CHCO — is considering entering into a formal business arrangement, especially with an other-than-Catholic party (organization, physician or other individual), senior leaders must be sure that:

- The business arrangement furthers the CHCO's vision and mission (this applies also to arrangements with Catholic parties)

- The prospective partner is compatible with the CHCO from a values perspective or, at a minimum, is not engaged in activities that are notably inconsistent with the CHCO's value commitments

- The CHCO's value commitments are adopted at a level proportionate to the facts and circumstances of the particular business arrangement

- The business arrangement meets cooperation guidelines, and any medical interventions with restrictions are acceptably structured or carved out

- A mission and ethics integration plan is developed prior to the close of the transaction and implemented effectively thereafter

The process and timing for ensuring these critical features are met should be sequenced in three phases: (See Appendix 1 for accompanying graphic.)

Phase 1: Assess (a) ability to further the CHCO's vision and mission, (b) compatibility with the CHCO's values, and (c) level of adoption of the CHCO's value commitments.

This phase is the most important in any discernment about a new business arrangement, and it should be the first order of business — even before financial and legal discussions. The focal points in this phase are whether and to what extent the business arrangement will further the CHCO's vision and mission; whether the prospective partner is compatible with the CHCO from a values perspective; and at what level should the CHCO's value commitments be adopted in the business arrangement.

During their discernment, senior leaders should ask and reflect upon these questions to reach a conclusion about whether the contemplated business arrangement will further the CHCO's vision and mission.

- Will it enable the CHCO to increase access to care, especially for the uninsured and those in economically, physically and socially marginalized communities?

- Will it enable the CHCO to improve community health as defined by key metrics related to mind, body, spirit and environment?

- Will it enhance the CHCO's ability to improve the patient experience, manage the health of populations and lower the total cost of care?

- Will it improve the CHCO's financial position and its ability to reinvest in the communities it serves?

If the answers to these questions are "yes," senior leaders may proceed to the second part of this phase.

If the answers are "no," generally the business arrangement should not be pursued. However, in limited situations, there may be some circumstances whereby the CHCO's senior leaders choose to discern further — perhaps because the business arrangement may be worth pursuing for the overall good of the ministry, or perhaps they want to proceed cautiously to determine if the arrangement can be restructured.

Regarding compatibility with the CHCO's values, senior leaders need ask only one question, and the answer must not be clouded by the desire to move forward with the business arrangement.

- Does the prospective partner exhibit evidence of living core aspects of the CHCO's values or, at a minimum, of not being engaged in activities inconsistent with CHCO's value commitments? (See Appendix 2.)

If the answer to this question is "yes," senior leaders may proceed to the third part of this phase.

If the answer is "no," the arrangement may still be pursued if the prospective partner is not engaged in activities that are notably inconsistent with the CHCO's value commitments, or if the CHCO will have majority control of the new company and can ensure that its value commitments are adopted.

Discernment in this part of Phase 1 can be complicated. As a general rule, the greater the control the CHCO has in the new business arrangement and the more the prospective partner will be integrated with the CHCO, the higher should be the level of adoption of the CHCO's value commitments.

At a minimum, the CHCO should seek to incorporate these value commitments into a new business arrangement whenever applicable:

- Creating a safe, just and diverse work environment and providing fair wages and benefits to all employees

- Protecting the sanctity of human life from conception to natural death. Actions such as direct abortion, assisted suicide, euthanasia and embryonic stem cell research are not permitted in a Catholic health care institution.

- Serving uninsured, underinsured, Medicaid and other vulnerable populations. For non-health care providers, this value commitment may be addressed through community outreach and charitable programs that seek to promote the health and well-being of the local community, with special emphasis on those living in poverty and at the margins of society.

Phase 2: Identify cooperation issues related to ERD-restricted interventions

Before a definitive agreement can be signed, the CHCO needs to identify any cooperation issues that might arise in the new business arrangement with an other-than-Catholic party engaged in medical interventions with restrictions as defined in the Ethical and Religious Directives for Catholic Health Care Services. Beyond issues related to the direct taking of life, ERD-restricted interventions typically include contraception, sterilization and in vitro fertilization.

For ethical guidance on the major types of business arrangements that senior leaders should use for discussions with a prospective partner, see Appendix 3. A qualified and experienced ethicist must complete a formal analysis addressing cooperation issues before a definitive agreement is signed.

Phase 3: Establish mission/ethics integration plan

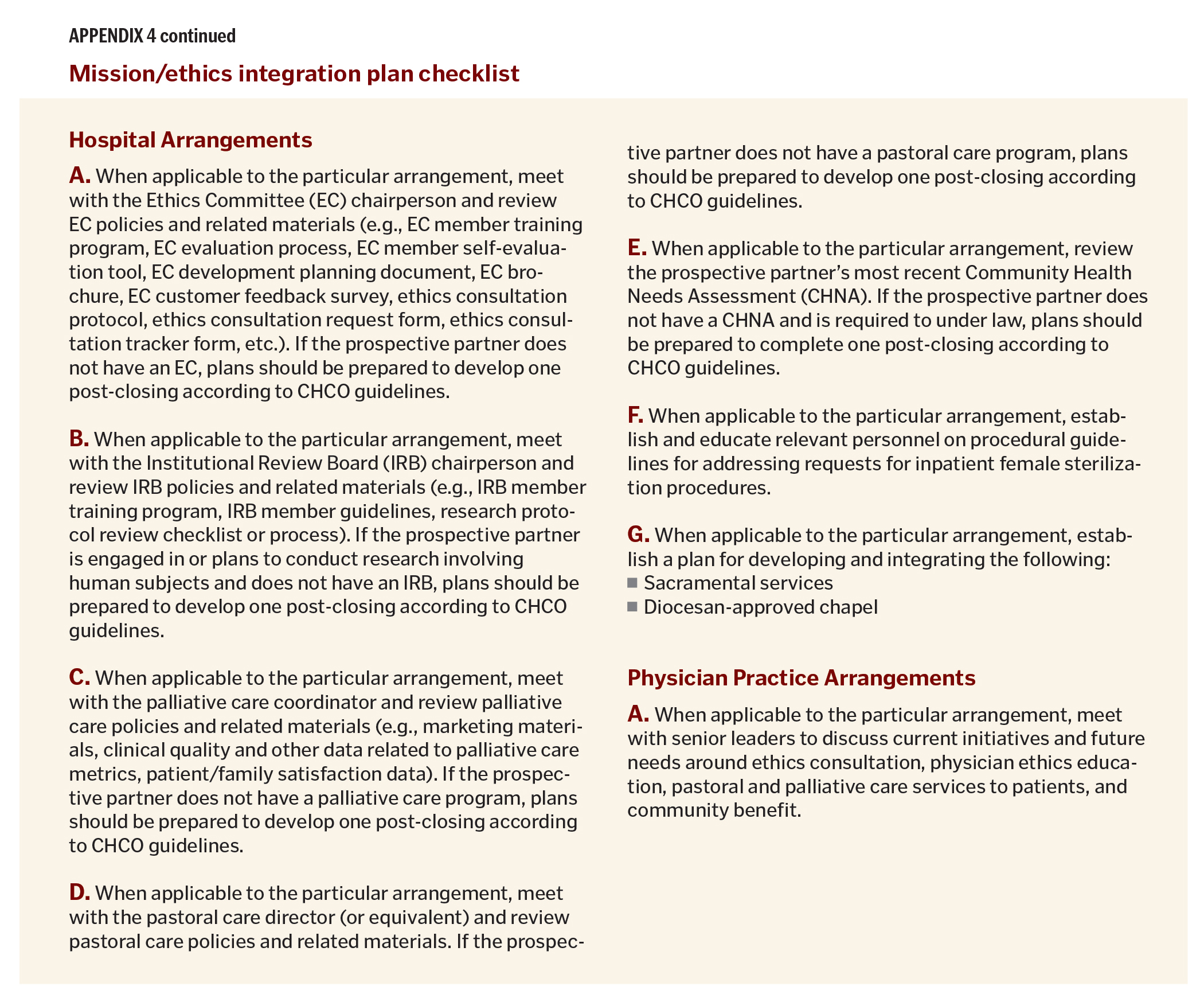

Before the definitive agreement is signed, system mission and ethics leaders should conduct an on-site assessment (if applicable) and document review to determine key integration opportunities based on the items detailed in Appendix 4.

The outcome of this phase should be a well-developed integration plan that clearly outlines the key mission and ethics components that will need to be developed under the new business arrangement, including a timeline, communication plan and a list of responsible parties that corresponds to each action item of the plan.

MICHAEL PANICOLA is senior vice president, mission, legal and government affairs, at SSM Health in St. Louis.

RON HAMEL is an ethicist in St. Louis.

NOTE

- See, for instance, Robin Respaut, "Grim Outlook for Healthcare, Hospital Sector in 2015: Rating Agencies," Reuters, Dec. 16, 2014.